Measles (Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention)

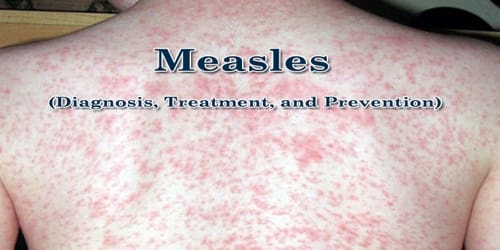

Definition: Measles is a viral disease that can spread rapidly. Also called rubeola, measles can be serious and even fatal for small children. Measles is an airborne disease which spreads easily through the coughs and sneezes of infected people. It may also be spread through contact with saliva or nasal secretions.

It is one of the most contagious vaccine-preventable infections in humans. The one antigenic type of the measles virus is only found in humans. This means that if high immunization rates are maintained, it may be possible to eradicate this virus, just like smallpox and polio.

Symptoms usually develop 10–12 days after exposure to an infected person and last 7–10 days. Initial symptoms typically include fever, often greater than 40 °C (104.0 °F), cough, runny nose, and inflamed eyes. Small white spots known as Koplik’s spots may form inside the mouth two or three days after the start of symptoms.

People most at risk are patients with a weak immune system, such as those with HIV, AIDS, leukemia, or a vitamin deficiency, very young children, and adults over the age of 20 years. Older people are more likely to have complications than healthy children over the age of 5 years.

Measles is caused by the measles virus, a single-stranded, negative-sense, enveloped RNA virus of the genus Morbillivirus within the family Paramyxoviridae. Measles is so contagious that if one person has it, 90% of nearby non-immune people will also become infected. Humans are the only natural hosts of the virus, and no other animal reservoirs are known to exist.

Even though a majority of patients recover from infection, measles can have serious complications. Early in infection, the brain tissue can become inflamed (encephalitis). A later complication can occur several years later, causing brain damage.

Measles has a low death rate in healthy children and adults, and most people who contract the measles virus recover fully. The risk of complications is higher in children and adults with a weak immune system. The measles vaccine is effective at preventing the disease and is often delivered in combination with other vaccines.

Diagnosis and Treatment of Measles: Clinical diagnosis of measles requires a history of fever of at least three days, with at least one of the following symptoms: a cough, coryza, or conjunctivitis. The doctor can usually diagnose measles based on the disease’s characteristic rash as well as a small, bluish-white spot on a bright red background — Koplik’s spot — on the inside lining of the cheek. If necessary, a blood test can confirm whether the rash is truly measles.

In most countries, measles is a notifiable disease. The doctor has to notify the authorities of any suspected cases. If the patient is a child, the doctor will also notify the school.

A child with measles should not return to school until at least 5 days after the rash appears.

Laboratory diagnosis of measles can be done with confirmation of positive measles IgM antibodies or isolation of measles virus RNA from respiratory specimens. Any contact with an infected person, including semen through sex, saliva, or mucus, can cause infection.

There are no medications that can kill off the virus (measles), so the only useful treatments are those that help relieve symptoms. Instead, the medications are generally aimed at treating superinfections, maintaining good hydration with adequate fluids, and pain relief. Some groups are also given vitamin A, like young children and the severely malnourished, which act as an immunomodulator that boosts the antibody responses to measles and decreases the risk of serious complications.

However, the doctor may recommend:

- acetaminophen to relieve fever and muscle aches

- rest to help boost the patient’s immune system

- plenty of fluids (six to eight glasses of water a day)

- humidifier to ease a cough and sore throat

- vitamin A supplements

If any people or child has measles, keep in touch with the doctor as they monitor the progress of the disease and watch for complications. Also, try these comfort measures:

- Take it easy. Get rest and avoid busy activities.

- Sip something. Drink plenty of water, fruit juice, and herbal tea to replace fluids lost by fever and sweating.

- Seek respiratory relief. Use a humidifier to relieve a cough and sore throat.

- Rest of eyes. If any people or their child finds bright light bothersome, as do many people with measles, keep the lights low or wear sunglasses. Also, avoid reading or watching television if light from a reading lamp or from the television is bothersome.

Over 95% of children fully vaccinated against modern measles are protected against the disease. In about 15% of cases, people may get a very mild, non-contagious form of measles about 10 days after vaccination. The measles vaccine is commonly given in the same injection as the mumps and rubella vaccine, in what is commonly known as MMR vaccine.

Prevention of Measles: Immunizations can help prevent a measles outbreak. The MMR vaccine is a three-in-one vaccination that can protect people and their children from the measles, mumps, and rubella (German measles). Adults who have never received an immunization can request the vaccine from their doctor.

Generally, the measles vaccine isn’t given to babies less than one-year-old, pregnant women, or people with severely damaged immune systems. If a pregnant woman or newborn baby is exposed to the measles virus, they will be given a transfusion of immune serum globulin instead. This contains special antibodies that defend the body against the virus.

In developing countries where measles is common, the World Health Organization recommend two doses of vaccine be given at six and nine months of age. Measles vaccination programs are often used to deliver other child health interventions, as well, such as bed nets to protect against malaria, antiparasite medicine, and vitamin A supplements, and so contribute to the reduction of child deaths from other causes.

The WHO estimates that measles vaccination programs led to a 79 percent drop in measles deaths globally, from 2000 to 2015, preventing around 20.3 million deaths.

Information Source: