The term McCarthyism defined a period of U.S. history during the 1950s when there was intense concern about Communist infiltration of American society. It took its name from U.S. Senator Joseph McCarthy, a Republican from Wisconsin, who was involved in accusing many people of being Communist or having Communist sympathies. These people were then often subjected to aggressive investigations, questioning by congressional committees. In many cases they faced harassment and, in some cases, what became known as “selective prosecution.”

After World War II, the U.S. government became increasingly worried about the establishment of Communist or pro-Communist governments throughout all of eastern Europe. Many people in the United States started to feel threatened by the Soviet Union. This certainly increased in 1949, when the Soviet Union exploded its first atomic bomb and the Communists were victorions in the Chinese civil war in the same year. With the start of the Korean War the following year, the idea of communism seeking to expand over the whole world was seen in many circles in the United States as a very real possibility.

In January 1950 Alger Hiss, a high-level official in the State Department, was convicted of perjury. He would have been charged with espionage, but the statute of limitations had run out. Instead, he was charged with lying when he testified before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, the major group involved in questioning suspected Communists.

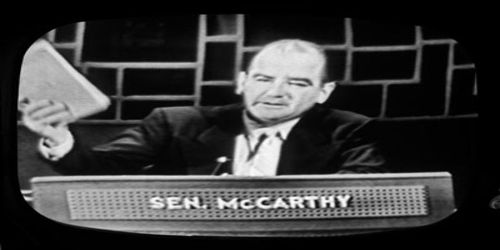

On February 9, 1950, Senator Joe McCarthy produced a piece of paper that he claimed contained a list of 205 people working in the State Department who were known to the secretary of state as having been members of the Communist Party. McCarthy received much press coverage, and the term McCarthyism has been traced to a Washington Post cartoon by Herblock, published on March 29, 1950, showing a tottering pillar on which an elephant—the symbol of the Republican Party—is being asked to stand.

In July 17, 1950, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were arrested. Both were members of the Communist Party, and the couple both worked on the Manhattan Project at the Los Alamos National Laboratory during the war. With the American government eager to find out how the Soviet Union had managed to explode their atomic bomb so quickly, investigations led to the Rosenbergs, who were charged with stealing atomic bomb secrets for the Soviet Union. The Rosenbergs were found guilty, although doubts were cast on the constitutionality and the applicability of the Espionage Act of 1917, under which they were tried, as well as the perceived bias of the trial judge, Irving R. Kaufman. The Rosenbergs were executed on June 19, 1953, being the first U.S. civilians to be executed for espionage, and the first Americans ever to be executed for espionage in peacetime.

With many high-profile cases like those of Alger Hiss and the Rosenbergs, it was not long before the FBI director, J. Edgar Hoover, started assigning increasingly large numbers of his agents to investigating Communists and suspected Communists. In this, the FBI were subsequently found to have broken laws, being involved in burglaries, opening mail, and installing illegal wiretaps.

From 1947 on, the House Un-American Activities Committee had started to question people connected with Hollywood, serving subpoenas on film actors, directors, and some screenwriters. The first 10, known as the “Hollywood Ten,” refused to cooperate and pleaded the First Amendment’s guarantee of free speech and free assembly. The defense was rejected, and eight of the 10 were jailed for a year, and two for six months. Thereafter, witnesses tended to plead the protection of the Fifth Amendment, refusing to give any evidence that might incriminate them. Those questioned could either use this as a defense or name other Communists.

Senator McCarthy came to head the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations. He then started searching through the card catalogs of the overseas library program of the State Department, finally getting them to remove books which were deemed to be communist or pro-communist. The blacklists then started, although in many ways these had been operating since November 1947, when Eric Johnston, president of the Motion Picture Association of America, issued a press release that came to be known as the Waldorf Statement.

Several hundred people were jailed during the McCarthy period, as it became known, with between 10,000 and 12,000 losing their jobs. A few scholars, such as John D’Emilio, have managed to show that more people were targeted for homosexuality than communism. In the film industry more than 300 actors, actresses, writers, and directors were not able to find work because of the blacklists.

In 1952 the U.S. Supreme Court voted to uphold the decision made in lower courts in Alder v. Board of Education of New York that state-based loyalty review panels could fire any teachers deemed subversive. As tensions mounted, Arthur Miller launched his attack on McCarthyism in his play The Crucible, using the Salem witch trials of 1692 as a metaphor in which the accusation was tantamount, in the public mind, to guilt.

It was Edward R. Murrow, the CBS broadcast journalist, who criticized McCarthy on March 9, 1954, on his “Report on Joseph R. McCarthy,” stating that the senator had been abusive toward witnesses. Soon afterward, when McCarthy attacked the U.S. Army’s chief counsel, Joseph Welch, Welch replied, “Have you no sense of decency, sir? At long last, have you left no sense of decency?” It was a rebuke that slowly led to a move away from McCarthyism.

Gradually, even President Dwight D. Eisenhower began to see McCarthy as extremely distasteful. In November 1954, when the Republicans lost control of the Senate, McCarthy was dumped from the Government Committee on Operations of the Senate. Soon afterward he was formally censured by a vote of 67 to 22 for conduct “contrary to Senate traditions.” McCarthy remained as a senator for another two years. He had always been a heavy drinker and died on May 2, 1957, from cirrhosis of the liver.

Information Source: