Human activities such as hiking, camping, bird-watching, and other forms of low-impact recreation can have an impact on wildlife behavior. When wildlife are frequently exposed to people, they can become habituated to human presence, which can cause changes in their behavior. For example, animals may start to feed or breed closer to human activity, which can increase the risk of conflict with people.

It’s important to be mindful of the impact that we have on wildlife and to take steps to minimize our impact. This can include following responsible recreation practices, such as staying on designated trails, keeping a safe distance from wildlife, and avoiding disturbing nesting or breeding sites. By being mindful of our impact and taking steps to minimize it, we can help protect wildlife and preserve the natural beauty of the environment for future generations to enjoy.

Even without hunting rifles, humans appear to have a significant negative impact on wildlife movement. A study of hiking trails in Glacier National Park before and after a COVID-19 closure adds to the theory that humans, like other apex predators, can create a “landscape of fear,” changing how species use an area simply by their presence.

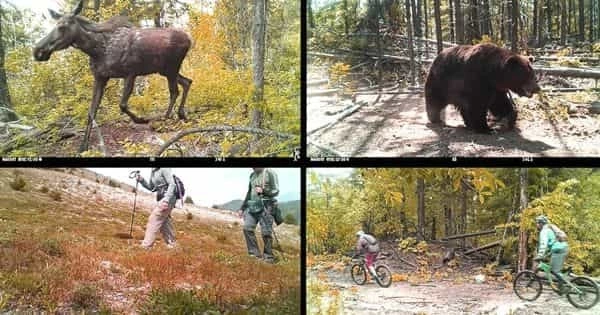

Researchers from Washington State University and the National Park Service discovered that when humans were present, 16 of 22 mammal species, including predators and prey, changed where and when they accessed areas. Some completely abandoned previously used locations, while others used them less frequently, and still others shifted to more nocturnal activities to avoid humans.

This study does not say that hiking is necessarily bad for wildlife, but it does have some effects on spatiotemporal ecology, or how and when wildlife uses a landscape.

Alissa Anderson

“We saw a lot of changes in how animals were using that same area when the park was open to the public and there were a lot of hikers and recreators using it,” said Daniel Thornton, WSU wildlife ecologist and senior author on the study published in the journal Scientific Reports. “What’s surprising is that there isn’t any other real human disturbance out there because Glacier is such a well-protected national park, so these responses are truly being driven by human presence and human noise.”

The researchers also expected to find “human shielding,” which occurs when human presence causes large predators to avoid an area, allowing smaller predators and possibly some prey species to use the area more frequently. They discovered this potential effect in only one species, the red fox, in this case. When the park was open, the foxes were more visible on and near trails, possibly because their competitors, coyotes, avoided those areas when humans were present.

Several species, including black bear, elk, and white-tailed deer, showed a decrease in use of trail areas when the park was open. Mule deer, snowshoe hare, grizzly bears, and coyotes have all reduced their daytime activity. A few, including cougars, appeared unconcerned about human presence.

While the influence of low-impact recreation is concerning, the researchers emphasized that more research is needed to determine if it has negative effects on the species’ survival.

“This study does not say that hiking is necessarily bad for wildlife, but it does have some effects on spatiotemporal ecology, or how and when wildlife uses a landscape,” said Alissa Anderson, a recent WSU master’s graduate, and the study’s first author. “They may not be on the trails as much, but they are using different areas, and how much does this affect a species’ ability to survive and thrive in a location? There are many unanswered questions about how this affects population survival.”

The study was inspired in part by the pandemic. Because both humans and wildlife enjoy using trails, the researchers had set up an array of camera traps near several trails in Glacier National Park to study lynx populations when COVID-19 struck. To prevent the virus from spreading to the nearby Blackfeet Indian Reservation, the park’s eastern portion was closed in 2020, with only administrators and researchers granted limited access.

This enabled Anderson, Thornton, and Glacier National Park co-author John Waller to conduct a natural experiment. They took photos in the summer of 2020, when the park was closed, and again in 2021, when it reopened.

More than 3 million people visit Glacier National Park each year, which spans nearly 1,600 square miles in northwestern Montana. It also has a diverse range of animals, including nearly all of the mammal species that have existed in the region historically.

According to Thornton, park managers must strike a balance between conservation and public use missions. “It’s obviously important that people are able to get out there, but there might be a level of which that starts to be problematic,” he said. “Some additional research could aid in gaining a better understanding of that and in developing some guidelines and goals.”