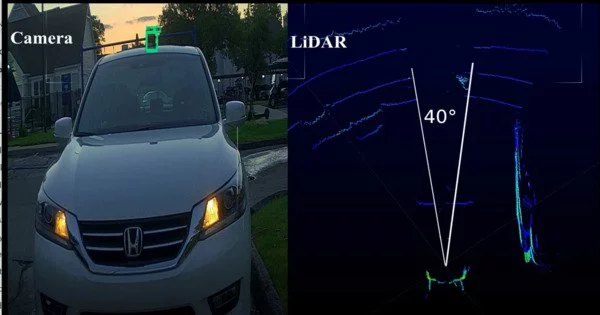

Researchers created the first-ever attack that creates a blind spot for lidar sensors steering autonomous vehicles, demonstrating that they can completely remove a moving pedestrian from the field of vision. To avoid obstacles and drive safely, self-driving cars, like human drivers before them, need to see what’s around them.

The most advanced autonomous vehicles typically employ lidar, a spinning radar-type device that serves as the vehicle’s eyes. Lidar constantly provides information about the distance to objects, allowing the car to determine what actions are safe to take. But it turns out that these eyes can be deceived.

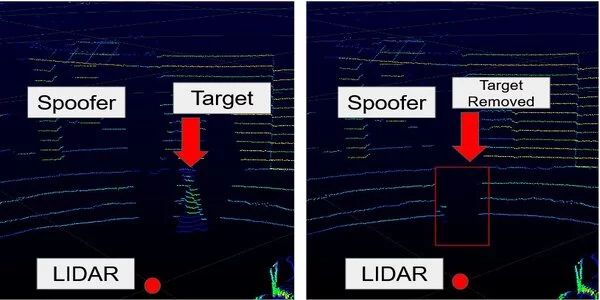

New research reveals that expertly timed lasers shined at an approaching lidar system can create a blind spot in front of the vehicle large enough to completely hide moving pedestrians and other obstacles. The deleted data causes the cars to think the road is safe to continue moving along, endangering whatever may be in the attack’s blind spot.

This is the first time that lidar sensors have been tricked into deleting data about obstacles.

The vulnerability was uncovered by researchers from the University of Florida, the University of Michigan, and the University of Electro-Communications in Japan. The scientists also provide upgrades that could eliminate this weakness to protect people from malicious attacks. The findings will be presented at the 2023 USENIX Security Symposium and are publicly available online.

We mimic the lidar reflections with our laser to make the sensor discount other reflections that are coming in from genuine obstacles. The lidar is still receiving genuine data from the obstacle, but the data are automatically discarded because our fake reflections are the only ones perceived by the sensor.

Sara Rampazzi

Lidar works by emitting laser light and capturing the reflections to calculate distances, much like how a bat’s echolocation uses sound echoes. The attack creates fake reflections to scramble the sensor.

“We mimic the lidar reflections with our laser to make the sensor discount other reflections that are coming in from genuine obstacles,” said Sara Rampazzi, a UF professor of computer and information science and engineering who led the study. “The lidar is still receiving genuine data from the obstacle, but the data are automatically discarded because our fake reflections are the only ones perceived by the sensor.”

The scientists demonstrated the attack on moving vehicles and robots with the attacker placed about 15 feet away on the side of the road. However, with upgraded equipment, it could be done from a greater distance. The technology required is fairly simple, but the laser must be perfectly timed to the lidar sensor and moving vehicles must be carefully tracked to keep the laser pointing in the right direction.

“It is primarily a matter of synchronizing the laser with the lidar device. The information you require is usually publicly available from the manufacturer” S. Hrushikesh Bhupathiraj, a UF doctoral student in Rampazzi’s lab and one of the study’s lead authors, agreed.

Using this technique, the scientists were able to delete data for static obstacles and moving pedestrians. They also demonstrated with real-world experiments that the attack could follow a slow-moving vehicle using basic camera tracking equipment. In simulations of autonomous vehicle decision making, this deletion of data caused a car to continue accelerating toward a pedestrian it could no longer see instead of stopping as it should.

This vulnerability could be addressed by updating the lidar sensors or the software that interprets the raw data. Manufacturers, for example, could train software to look for the telltale signatures of the spoofed reflections added by the laser attack.

“Disclosing this liability allows us to build a more reliable system,” said Yulong Cao, a doctoral student at Michigan and the study’s primary author. “In our paper, we show that previous defense strategies are insufficient, and we propose changes to address this weakness.”