The distribution of precipitation is changing, the sea level is rising, extreme weather events are increasing in frequency, the ocean is becoming more acidic, and anoxic zones are still expanding as a result of the catastrophic climate crisis.

“The climate crisis they themselves caused is likely the greatest challenge that homo sapiens have faced in their 300,000-year history,” says Prof Hans-Otto Pörtner, head of the Integrative Ecophysiology Section at the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research.

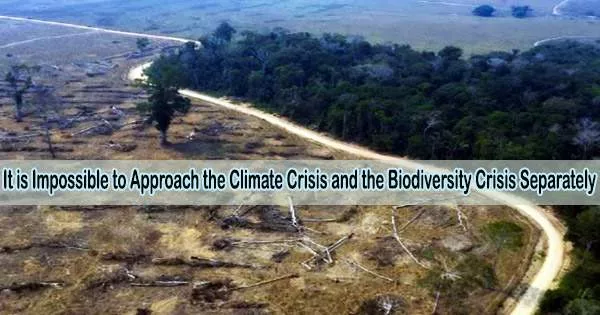

“Yet at the same time another, equally dangerous crisis is unfolding, one that is often overlooked the dramatic loss of plant and animal species across the planet. The two catastrophes the climate crisis and biodiversity crisis are interdependent and mutually amplifying, which is why they should never be seen as two separate things. Consequently, our review study shows in detail the connections between the climate crisis and biodiversity crisis and presents solutions for addressing both catastrophes and mitigating their social impacts, which are already dramatic.”

18 international experts contributed to the study. It was just published in the journal Science and was the result of a virtual scientific session that 62 researchers from 35 different countries participated in December 2020.

The workshop was jointly coordinated by two organisations belonging to the United Nations: the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Hans-Otto Pörtner has served as lead author on various Assessment Reports and Special Reports for the IPCC and has been Co-Chair of its Working Group II, tasked with assessing the current state of knowledge on global warming impacts, since 2015.

With the aid of grim statistics, the specialists in their study detail the rapidly escalating loss of species. They estimate that human actions have impacted nearly 75% of the land area and 66% of the oceans on our globe.

We’re unlikely to reach the new global biodiversity, climate and sustainability targets planned for 2030 and 2050 if the individual institutions fail to collaborate more intensively. Take for example the separate UN conventions on biodiversity and climate protection, i.e., the Convention on Biological Diversity and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. They address the two crises too separately and are also focused on the national interests of the parties to the conventions. Here, we urgently need a comprehensive approach if we still hope to reach the targets.

Hans-Otto Pörtner

This has happened to such a degree that more species are in danger of extinction now than at any other moment in human history, including the loss of about 80% of the biomass from animals and 50% of the biomass from plants.

In this way, both global warming and the degradation of natural ecosystems, which also reduces the ability of species, soils, and sediments to store carbon, exacerbate the loss of biodiversity.

Because each organism has a certain tolerance range for changes to its environmental conditions (e.g. temperature), global warming is also causing species’ habitats to shift. Mobile species follow their temperature range and migrate toward the poles, to higher elevations (on land, mountain ranges) or to greater depths (in the ocean).

Because sessile organisms like corals are trapped in a temperature trap and can only change their habitat very gradually over generations, big coral reefs may eventually completely vanish.

If mobile species can no longer find any environment with adequate temperatures to colonize, they may also encounter climatic dead ends in the form of mountain peaks, the coasts of landmasses and islands, at the poles, and in the depths of the ocean.

The researchers suggest an ambitious mix of emissions reduction, restoration and protection measures, rational land-use management, and encouraging cross-institutional skills among political actors to confront these numerous issues.

“Needless to say, a massive reduction of greenhouse-gas emissions and reaching the 1.5-degree target continue to be at the top of the priorities list,” says Hans-Otto Pörtner. “In addition, at least 30 percent of all land, freshwater and marine zones must be protected or restored so as to prevent the greatest biodiversity losses and preserve natural ecosystems’ ability to function. This in turn will help us to combat climate change. For example, the extensive restoration of just 15 percent of the zones that have been converted for land use could be sufficient to prevent 60 percent of the expected extinction events. This would also allow up to 300 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere to be removed and fixed on a long-term basis; that amounts to 12 percent of all the carbon emitted since the dawn of the industrial era.”

The authors of the study also advocate for a more contemporary method of managing land use, one in which protected areas are not seen as solitary havens for biodiversity. Instead, they must be a part of a global network, both on land and in the sea, that connects relatively unexplored areas via species’ migration routes.

In this regard, it is important to help local communities and Indigenous peoples in their efforts to preserve and restore nature. The emphasis should be on sustainability when it comes to areas that are heavily used for fishing and agriculture.

Modern ideas are needed to assure stable food supplies for all people as well as resource-conserving modes of use. Priority should be given to ideas in this area that increase carbon dioxide uptake and carbon fixation in biomass and soils.

Additionally, habitats must be established for species, such as the insects that pollinate fruit trees, that make harvests feasible in the first place. Last but not least, enhancing the carbon dioxide balance needs to be the top priority in cities.

“In the future, all of this will only work if for all approved measures climate protection, biodiversity preservation, and social advantages for local communities are pursued simultaneously,” says Pörtner.

“We’re unlikely to reach the new global biodiversity, climate and sustainability targets planned for 2030 and 2050 if the individual institutions fail to collaborate more intensively. Take for example the separate UN conventions on biodiversity and climate protection, i.e., the Convention on Biological Diversity and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. They address the two crises too separately and are also focused on the national interests of the parties to the conventions. Here, we urgently need a comprehensive approach if we still hope to reach the targets.”