What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger is a saying that you’ve probably heard, either from Kelly Clarkson or Nietzsche. In both cases, and as the expression is now frequently used, it fundamentally indicates that overcoming challenges makes you stronger.

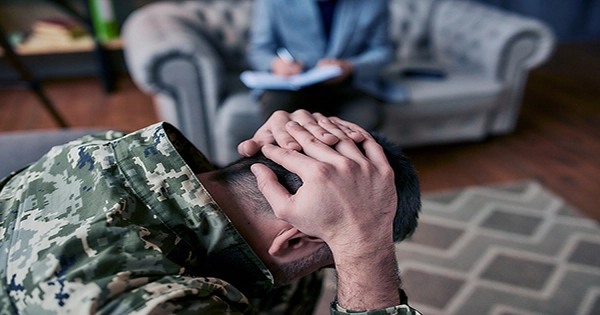

According to psychologist Eranda Jayawickreme, who has studied “post-traumatic growth,” “it’s almost like a cultural touchstone.” “We feel that when horrible things happen, we will utilize it as a chance to get better. It’s almost like a default attitude toward trauma.”

But does the saying have any basis in reality? According to Jayawickreme, it’s difficult and even if there is some truth to it, it could not be useful as a notion.

According to some studies, traumatic occurrences can be followed by growth (and increased relationship satisfaction), as well as an increase in self-esteem.

In an article published in the American Psychological Association, the authors stated that “a positive tendency has been found for self-esteem, positive relationships, and mastery in prospective studies after both positive and negative events.”

“The widely held belief that bad life events have a greater impact than positive ones was not supported by any general data that we could find. There was no real development in terms of purpose or spirituality. Results did not significantly differ between event and control groups in the majority of studies with control groups, demonstrating that changes in the outcome variables cannot just be attributed to the occurrence of the investigated life events.”

One issue with conducting this type of research is that you can’t make your participants experience trauma (unless you travel back to the early 1900s and really crack on). By asking individuals to rate how they are now compared to how they were previously, you can get data by relying on their recollections of their pre-trauma life.

One set of researchers circumvented this by, in essence, allowing the trauma to occur throughout the course of the study. In a study that was published in Psychological Science, researchers recruited 1,200 undergraduate students who were “at the peak age for trauma exposure” to participate. The students were asked to complete a variety of questionnaires that measured satisfaction in areas of life that were thought to be impacted by traumatic events.

The same questionnaires, as well as one on life events that had occurred during the two-month wait and a usual post-traumatic growth questionnaire asking participants about changes to themselves as a result of the traumatic experiences, were then given to the students.

In the most recent questionnaire, there were rating phrases such as “I feel more self-reliant” and “I feel more connected to others.”

The researchers gave the scenario of “a close friend killed by a drunk driver” as one example of a highly traumatic occurrence that 122 of the students had encountered and regarded as having caused them significant distress.

The team stated in its discussion that “it would be erroneous to assume from our findings that people cannot evolve in positive ways following threatening life experiences.” In fact, only a small number of the subjects showed actual change, albeit it is unknown if this change is related to the participants’ traumatic experiences.

However, there was a minimal link between participant perceptions of their own growth and improvements in these psychological measures when looking at the measures of life satisfaction that were gathered during both study phases.

All of this shows that growth reports from the past don’t accurately reflect genuine pre- and post-trauma changes, they continued.

The adage “what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger” may not only be ambiguous, but it also poses a risk to those who have recently gone through trauma.

Consider the message it conveys: Suffering is beneficial in the long term, and trauma survivors are more resilient than non-survivors, Jayawickreme and colleague Frank J. Infurna said in an article on the subject for The Conversation. They go on to say that those who are still experiencing difficulties months or years after a traumatic occurrence could feel “weak” if they haven’t made the same “development.”

“Adversity can actually help people grow. They can get stronger, enhance the caliber of their connections, and boost their self-worth. However, it probably doesn’t occur as frequently as most people and some researchers think.”

“Growth also shouldn’t be viewed as a universal objective. Just going back to where they were prior to the trauma may be an ambitious enough objective for many people.”