Fruit flies are well-known for their sweet tooth, but new research suggests they may also provide insights into how animals detect – and avoid – high salt concentrations. Zoologists used mutant fruit flies to discover a new high-salt receptor on the tongue of Drosophila: receptor IR7c. IR7c regulates the ability of insects to detect dangerously high concentrations of salt, typically greater than 0.25 moles per liter, or roughly half the saltiness of sea water.

Fruit flies are known for their sweet tooth, but new research suggests they may also provide insights into how animals detect – and avoid – high salt concentrations. Using mutant fruit flies, zoologists from the University of British Columbia discovered a new high-salt receptor on the tongue of Drosophila: receptor IR7c. IR7c governs insects’ ability to detect dangerously high concentrations of salt, typically greater than 0.25 moles per litre, or roughly half as salty as sea water.

“In flies, high salt avoidance is driven by both bitter taste neurons and a separate class of neurons dedicated entirely to detecting high concentrations of salt,” says PhD student Sasha McDowell, lead author of the study published today in Current Biology.

High salt taste has mostly been thought of as a non-specific process, but it turns out flies care about which salts they’re tasting. This may be because calcium ions are toxic to flies, and they should avoid them at any concentration. But sodium is an important part of any diet, so flies need to like the taste of sodium until concentrations get high enough to be harmful.

Professor Michael Gordon

“When we turned off the IR7c receptor, the flies’ typical physiological responses and behavioral aversion to high concentrations of monovalent salts like simple sodium chloride vanished.”

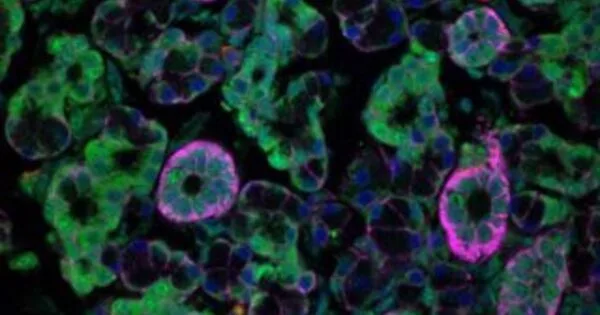

Tastes are detected by gustatory receptor neurons located throughout the body, including the labellum at the tip of their mouths, the pharynx, or throat, and even parts of their legs. In the case of fruit flies, researchers had already identified two co-receptors involved in detecting salt and a variety of other chemicals, IR76b and IR25a, but a salt-specific receptor on the labellum, IR7c, was unknown.

Surprisingly, even with their IR7c receptor turned off, the mutant flies responded normally to high concentrations of less nutritionally abundant divalent salts such as calcium.

“High salt taste has mostly been thought of as a non-specific process, but it turns out flies care about which salts they’re tasting,” says Professor Michael Gordon, senior author of the study. “This may be because calcium ions are toxic to flies, and they should avoid them at any concentration. But sodium is an important part of any diet, so flies need to like the taste of sodium until concentrations get high enough to be harmful.”

All animals require salt to survive; sodium is required for nerve and muscle function and aids in fluid regulation in the body. Too much salt, on the other hand, can cause dehydration, kidney failure, and other negative effects.

“The receptor we discovered in flies isn’t present in mammals,” Dr. Gordon explains, “but because high salt taste hasn’t been fully understood in any animal, our research may provide clues to mechanisms in other species.”

“If there’s one thing I’ve learned from studying salt taste, it’s that things are always more complicated and fascinating than we expect!”

When the weather turns cold, flies look for more than just food. Typical buildings have numerous construction flaws that allow scented warm air streamers to escape, attracting flies in need of shelter. They have difficulty finding their way out once inside because the most obvious path through brightly lit windows is frequently blocked by glass or screening.

It doesn’t take much to feed a fly, and they can detect even small amounts of stray food that you may have missed. Furthermore, their food taste may overlap with yours, but it is much broader, including organic materials you would not consider edible.