The primary genetic risk variation for severe COVID-19, which we received from Neandertals, is unexpectedly widespread. According to a new study, the same gene mutation that increases the risk of becoming critically ill with COVID-19 also protects against another catastrophic disease – it reduces a person’s risk of catching HIV by 27%.

The key genetic risk factor for severe COVID-19 was introduced into current human populations 50,000 to 70,000 years ago via gene flow from Neandertals. Although there is no clear evidence for positive selection on the risk haplotype, its frequency has increased since the Last Glacial Maximum and is extraordinarily frequent now, with carrier frequencies of 16% and 50% in Europe and South Asia, respectively. Given the prevalence of this genetic variant, it is of interest to consider whether it may offer protection against some pathogen other than severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2, either today or in the past.

Our genetic variants can either enhance or decrease our risk of becoming critically unwell with COVID-19. The primary genetic risk variation for severe COVID-19, which we received from Neandertals, is unexpectedly common. This raises the question of whether carrying this variation is genuinely advantageous.

We now know that this COVID-19 risk variation offers HIV protection. However, it was most likely protection against another disease that increased its prevalence when the last ice age.

Hugo Zeberg

Hugo Zeberg, a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology (MPI-EVA) in Germany and Karolinska Institutet in Sweden, discovered that the same gene variant that increases the risk of becoming seriously ill with COVID-19 also protects against another serious disease – it reduces a person’s risk of contracting HIV by 27%. This research was reported in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

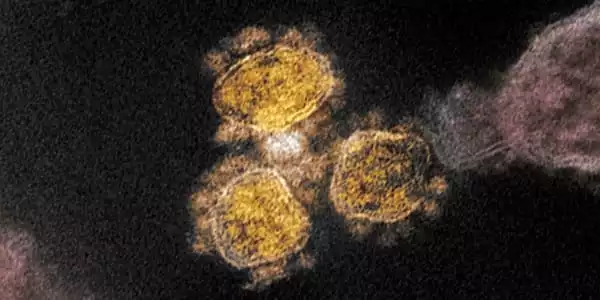

When infected with SARS-CoV-2, some people become critically ill, whereas others have relatively minor symptoms or none at all. Aside from risk factors including old age and chronic conditions like diabetes, our genetic ancestry also influences our individual COVID-19 severity risk.

Hugo Zeberg at Karolinska Institutet and MPI-EVA and Svante Pääbo at MPI-EVA demonstrated in the autumn of 2020 that we inherited the key genetic risk factor for severe COVID-19 from Neandertals. The same researcher duo analyzed this variant in ancient human DNA in the spring of 2021 and discovered that its frequency had increased dramatically since the previous ice age.

In fact, it has become unexpectedly common for a genetic variant inherited from Neandertals. Hence, it may have had a favorable impact on its carriers in the past. “This major genetic risk factor for COVID-19 is so common that I started wondering whether it might actually be good for something, such as providing protection against another infectious disease,” says Hugo Zeberg, who is the sole author of the new study in PNAS.

The genetic risk factor is found on chromosome 3 in a gene-rich area. Several genes in its vicinity encode immune system receptors. CCR5 is one of these receptors that the HIV virus uses to infect white blood cells. Zeberg discovered that participants with the COVID-19 risk factor had less CCR5 receptors. This prompted him to investigate whether they were also at a decreased risk of becoming infected with HIV.

He discovered that carriers of the COVID-19 risk variant had a 27 percent decreased chance of contracting HIV by analyzing patient data from three major biobanks (FinnGen, UK Biobank, and Michigan Genomic Initiative). “This demonstrates how a genetic mutation can be both good and bad: It’s bad news if a person develops COVID-19, but it’s good news because it protects against HIV infection” Zeberg explains.

However, because HIV first emerged in the twentieth century, immunity to this infectious disease cannot explain why the genetic risk mutation for COVID-19 became so prevalent among humans as early as 10,000 years ago. “We now know that this COVID-19 risk variation offers HIV protection. However, it was most likely protection against another disease that increased its prevalence when the last ice age” Zeberg draws a close.

In any event, this genetic mutation is a two-edged sword: it had catastrophic implications during the last two years of the COVID-19 pandemic, but it has also provided significant protection against HIV over the subsequent forty years. Its involvement in past and future pandemics is unknown.