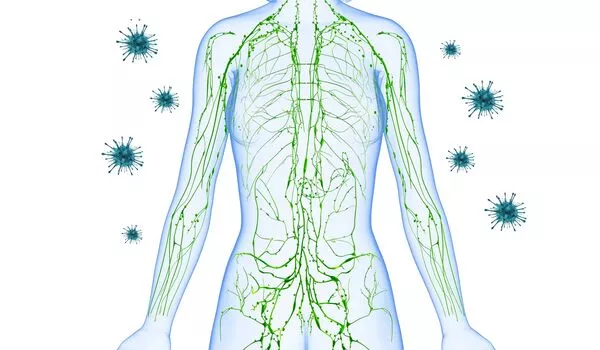

Regular exercise has a variety of immune-boosting benefits, contributing to overall health and well-being. According to mouse studies, the anti-inflammatory properties of exercise may result from immune cells mobilized to combat exercise-induced inflammation. Immune cells protect muscles by lowering interferon levels, which are a key driver of chronic inflammation, inflammatory diseases, and aging.

Since an early 20th-century study revealed a spike in white cells in the blood of Boston marathon runners following the race, researchers have been fascinated by the link between exercise and inflammation. A new Harvard Medical School study published in Science Immunology may provide a molecular explanation for this century-old observation.

The study in mice suggests that the immune system may play a role in the beneficial effects of exercise. It demonstrates that exertion-induced muscle inflammation mobilizes inflammation-fighting T cells, or Tregs, which improves the muscles’ ability to use energy as fuel and overall exercise endurance.

The immune system, and the T cell arm in particular, has a broad impact on tissue health that goes beyond protection against pathogens and controlling cancer. Our study demonstrates that the immune system exerts powerful effects on the muscle during exercise.

Diane Mathis

Long known for their role in combating the abnormal inflammation associated with autoimmune diseases, Tregs are now emerging as key players in the body’s immune responses during exercise, according to the research team.

“The immune system, and the T cell arm in particular, has a broad impact on tissue health that goes beyond protection against pathogens and controlling cancer. Our study demonstrates that the immune system exerts powerful effects inside the muscle during exercise,” said study senior investigator Diane Mathis, Morton Grove-Rasmussen Professor of Immunology in the Blavatnik Institute at HMS.

Mice are not people, and the findings remain to be replicated in further studies, the researchers cautioned. However, the study is an important step toward detailing the cellular and molecular changes that occur during exercise and confer health benefits.

Understanding the molecular underpinnings of exercise

Protecting against cardiovascular disease, lowering the risk of diabetes, and protecting against dementia. Exercise has been shown to have numerous health benefits. But how exactly does exercise make us healthier? For a long time, researchers have been intrigued by the question.

The new findings come as researchers work harder to understand the molecular underpinnings of exercise. Untangling the immune system’s role in this process is only one aspect of these efforts.

“We’ve known for a long time that physical exertion causes inflammation, but we don’t fully understand the immune processes involved,” said Kent Langston, a postdoctoral researcher in the Mathis lab and study first author. “Our study shows, at very high resolution, what T cells do at the site where exercise occurs, in the muscle.”

Most previous research on exercise physiology has focused on the role of various hormones released during exercise and their effects on different organs such as the heart and the lungs. The new study unravels the immunological cascade that unfolds inside the actual site of exertion — the muscle.

T cell heroes and inflammation-fueling villains

Exercise is known to cause temporary damage to the muscles, unleashing a cascade of inflammatory responses. It boosts the expression of genes that regulate muscle structure, metabolism, and the activity of mitochondria, the tiny powerhouses that fuel cell function. Mitochondria play a key role in exercise adaptation by helping cells meet the greater energy demand of exercise.

In the new study, the team analyzed what happens in cells taken from the hind-leg muscles of mice that ran on a treadmill once and animals that ran regularly. Then, the researchers compared them with muscle cells obtained from sedentary mice.

The muscle cells of the mice that ran on treadmills, whether once or regularly, showed classic signs of inflammation — greater activity in genes that regulate various metabolic processes and higher levels of chemicals that promote inflammation, including interferon. Both groups had elevated levels of Treg cells in their muscles. Further analyses showed that in both groups, Tregs lowered exercise-induced inflammation. None of those changes were seen in the muscle cells of sedentary mice.

However, the metabolic and performance benefits of exercise were apparent only in the regular exercisers – the mice that had repeated bouts of running. In that group, Tregs not only subdued exertion-induced inflammation and muscle damage, but also altered muscle metabolism and muscle performance, the experiments showed. This finding aligns with well-established observations in humans that a single bout of exercise does not lead to significant improvements in performance and that regular activity over time is needed to yield benefits.

Further research confirmed that Tregs were indeed to blame for the broader benefits observed in regular exercisers. Animals lacking Tregs experienced uncontrolled muscle inflammation, as evidenced by the rapid accumulation of inflammation-promoting cells in their hindleg muscles. Their muscle cells also had unusually swollen mitochondria, indicating a metabolic problem.

More importantly, animals lacking Tregs did not adapt to increasing exercise demands over time in the same way that mice with intact Tregs did. They did not get the same overall benefits from exercise and had lower aerobic fitness.

These animals’ muscles also had high levels of interferon, a known inflammatory factor. Further research revealed that interferon directly acts on muscle fibers, altering mitochondrial function and limiting energy production. In mice lacking Tregs, blocking interferon prevented metabolic abnormalities and improved aerobic fitness.

“The villain here is interferon,” Langston explained. “In the absence of guardian Tregs to counter it, interferon went on to cause uncontrolled damage.”

Interferon is known to promote chronic inflammation, a process that underpins many chronic diseases and age-related conditions, and it has become a tempting target for anti-inflammatory therapies. Tregs have also piqued the interest of scientists and industry as potential treatments for a variety of immunologic conditions characterized by abnormal inflammation.

According to the researchers, the study findings provide a glimpse into the cellular innerworkings of exercise’s anti-inflammatory effects and highlight its importance in harnessing the body’s own immune defenses.

There are efforts underway to develop Treg-targeting interventions in the context of specific immune-mediated diseases. While immunologic conditions caused by abnormal inflammation necessitate carefully calibrated therapies, the researchers suggest that exercise is another way to combat inflammation.

“Our research suggests that with exercise, we have a natural way to boost the body’s immune responses to reduce inflammation,” Mathis said in a statement. “We’ve only looked in the muscle, but it’s possible that exercise is boosting Treg activity elsewhere in the body as well.”