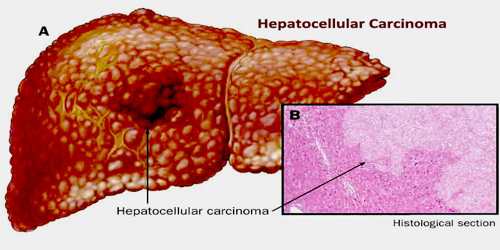

Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Definition

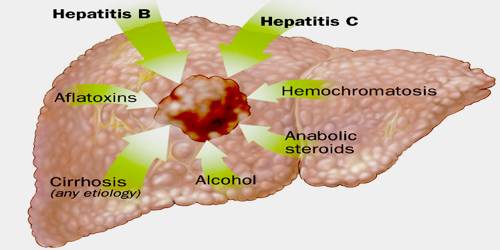

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a cancer that starts in the liver. It is the most common type of primary liver cancer in adults, and is the most common cause of death in people with cirrhosis. It occurs in the setting of chronic liver inflammation, and is most closely linked to chronic viral hepatitis infection (hepatitis B or C) or exposure to toxins such as alcohol or aflatoxin. If caught early, it can sometimes be cured with surgery or transplant. In more advanced cases it can’t be cured, but treatment and support can help people live longer and better.

Hepatocellular carcinoma is not the same as metastatic liver cancer, which starts in another organ (such as the breast or colon) and spreads to the liver. In most cases, the cause of liver cancer is long-term damage and scarring of the liver (cirrhosis). Cirrhosis may be caused by:

- Alcohol abuse

- Autoimmune diseases of the liver

- Hepatitis B or C virus infection

- Inflammation of the liver that is long-term (chronic)

- Iron overload in the body (hemochromatosis)

People with hepatitis B or C are at high risk of liver cancer, even if they do not develop cirrhosis.

The vast majority of HCC occurs in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, in countries where hepatitis B infection is endemic and many are infected from birth. The incidence of HCC in the United States and other developing countries is increasing due to an increase in hepatitis C virus infections. It is more common in male than females for unknown reasons.

Causes, Sign and Symptoms of Hepatocellular Carcinoma

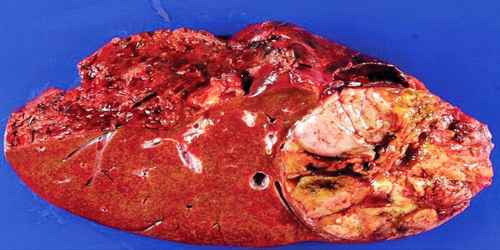

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a primary malignancy of the liver and occurs predominantly in patients with underlying chronic liver disease and cirrhosis. The cell(s) of origin are believed to be the hepatic stem cells, although this remains the subject of investigation. Tumors progress with local expansion, intrahepatic spread, and distant metastases.

Doctors aren’t sure exactly what causes all cases of hepatocellular carcinoma, but they’ve identified some things that may increase people’s risk for getting it:

- Hepatitis B or hepatitis C. Hepatocellular cancer can start many years after you’ve had one of these liver infections. Both are passed through blood, such as when drug users share needles. Blood tests can show whether you have hepatitis B or C.

- Cirrhosis. This serious disease happens when liver cells are damaged and replaced with scar tissue. Many things can cause it: hepatitis B or C infection, alcohol drinking, certain drugs, and too much iron stored in the liver.

- Heavy drinking. Having more than two alcoholic drinks a day for many years raises people’s risk of hepatocellular cancer. The more people drink, the higher their risk.

- Obesity and diabetes. Both conditions raise your risk of liver cancer. Obesity can lead to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, which can lead to hepatocellular carcinoma. The higher risk from diabetes may be due to high insulin levels in people with diabetes or from liver damage caused by the disease.

- Iron storage disease. This causes too much iron to be stored in the liver and other organs. People who have it may develop hepatocellular carcinoma.

- Aflatoxin. This harmful substance, which is made by certain types of mold on peanuts, corn, and other nuts and grains, can cause hepatocellular carcinoma.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is now the third leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide, with over 500,000 people affected. The incidence of HCC is highest in Asia and Africa, where the endemic high prevalence of hepatitis B and hepatitis C strongly predisposes to the development of chronic liver disease and subsequent development of HCC.

Most cases of HCC occur in people who already have symptoms of chronic liver disease. They may present either with worsening of symptoms or may be without symptoms at the time of cancer detection. HCC may directly present with yellow skin, abdominal swelling due to fluid in the abdomen, easy bruising from blood clotting abnormalities, loss of appetite, unintentional weight loss, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, or feeling tired.

Diagnosis, Treatment and Preventions of Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Methods of diagnosis in HCC have evolved with the improvement in medical imaging. The evaluation of both asymptomatic patients and those with symptoms of liver disease involves blood testing and imaging evaluation. Although historically a biopsy of the tumor was required to prove the diagnosis, imaging (especially MRI) findings may be conclusive enough to obviate histopathologic confirmation. The most common sites of metastasis are the lung, abdominal lymph nodes, and bone.

There are many treatments for hepatocellular carcinoma.

Radiation – This uses high-energy rays to kill patient’s cancer cells. Two types of radiation therapy can treat hepatocellular carcinoma:

- External: Patient’s will lie on a table while a large machine aims beams of radiation at specific spots on their chest or belly.

- Internal: A doctor injects tiny radioactive particles into the artery that sends blood to their liver. These block or destroy the blood supply to the tumor in their liver.

Radiation therapy can cause side effects, including nausea, vomiting, or tiredness, but these symptoms go away when treatment is done.

Chemotherapy – To treat cancer, doctors often place chemotherapy drugs directly into patient’s liver. It’s a process called “chemoembolization.” Doctor puts a thin, flexible tube into the artery that supplies blood to patient’s liver. The tube delivers a chemo drug combined with another drug that helps to block the artery. The goal is to kill the tumor by starving it of blood. Their liver still gets the blood it needs through another blood vessel.

Alcohol Injection – This is also called “percutaneous ethanol injection.” An ultrasound, which uses sound waves to see structures in patient’s body, helps their doctor guide a thin needle into the tumor. Then he/she injects ethanol (alcohol) to destroy the cancer.

Surgical Resection – Surgical resection to remove the tumor while preserving enough remaining healthy liver to maintain normal physiologic function. Surgical removal results in favorable prognosis, but only 10-15% of patients are suitable for surgical resection. This is often because of extensive disease or poor underlying liver function.

Liver Transplantation – Liver transplantation to replace the diseased liver with a cadaveric liver or a living donor graft has historically low survival rates (20%-36%). Studies from the late 2000 obtained higher survival rates ranging from 67% to 91%. If the liver tumor has metastasized, the immuno-suppressant post-transplant drugs decrease the chance of survival. Considering this objective risk in conjunction with the potentially high rate of survival, some recent studies conclude that: “LTx can be a curative approach for patients with advanced HCC without extrahepatic metastasis”.

Since hepatitis B or C is one of the main causes of hepatocellular carcinoma, prevention of this infection is key to then prevent hepatocellular carcinoma. Thus, childhood vaccination against hepatitis B may reduce the risk of liver cancer in the future. In the case of patients with cirrhosis, alcohol consumption is to be avoided. Also, screening for hemochromatosis may be beneficial for some patients.

Resection may benefit certain patients, albeit mostly transiently. Many patients are not candidates given the advanced stage of their cancer at diagnosis or their degree of liver disease and, ideally, could be cured by liver transplantation. Globally, only a fraction of all patients have access to transplantation, and, even in the developed world, organ shortage remains a major limiting factor. In these patients, local ablative therapies, including radiofrequency ablation (RFA), chemoembolization, and potentially novel chemotherapeutic agents, may extend life and provide palliation.

Reference: