Dinosaurs, like us, became ill and injured. Paleopathologists, experts in ancient disease and injuries, are gaining tantalizing insights into dinosaur behavior and evolution by detecting these medical conditions in fossils – how a dinosaur moved through its world, the relationship between predator and prey, and how dinosaurs of the same species interacted.

In the fossilized remains of a dinosaur that lived nearly 150 million years ago, scientists discovered the first evidence of a unique respiratory infection. Researchers examined the remains of an immature diplodocid – a long-necked herbivorous sauropod dinosaur like ‘Brontosaurus’ – from the Mesozoic Era’s Late Jurassic Period. Dolly, the dinosaur discovered in southwest Montana, had evidence of an infection in the area of its neck vertebrae.

A team of scientists from across the country, led by University of New Mexico Research Assistant Professor Ewan Wolff, discovered the first evidence of a rare respiratory infection in the fossilized remains of a dinosaur that lived nearly 150 million years ago.

We must continue to learn more about ancient diseases. If we look hard enough, we might learn more about the evolution of immunity and infectious disease. When we collaborate across multiple specialties – veterinarians, anatomists, paleontologists, paleopathologists, and radiologists – we can get a more complete picture of ancient disease.

Ewan Wolff

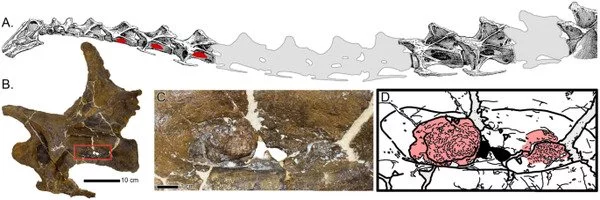

Researchers examined the remains of an immature diplodocid – a long-necked herbivorous sauropod dinosaur like “Brontosaurus” – from the Mesozoic Era’s Late Jurassic Period. The dinosaur nicknamed “Dolly,” discovered in southwest Montana, had evidence of an infection in the area of its neck vertebrae.

They study, led by Cary Woodruff of the Great Plains Dinosaur Museum, identified never before seen abnormal bony protrusions that had an unusual shape and texture. These protrusions were located in an area of each bone where they would have been penetrated by air sacs. Air sacs are non-oxygen exchanging parts of the respiratory system in modern birds that are also present in dinosaurs. The air sacs would have ultimately connected to “Dolly’s” lungs and formed part of the dinosaur’s complex respiratory system. CT imaging of the irregular protrusions revealed that they were made of abnormal bone that most likely formed in response to an infection.

“We’ve all experienced these same symptoms – coughing, trouble breathing, fever, and here’s a 150-million-year-old dinosaur that likely felt as miserable as we all do when we’re sick.” Woodruff said.

These findings are significant, according to the researchers, because Dolly was thought to be a non-avian dinosaur, and sauropods, like Dolly, did not evolve into birds; only avian theropods did. The authors speculate that this respiratory infection was caused by a fungal infection similar to aspergillosis, a common respiratory illness that currently affects birds and reptiles and can lead to bone infections. This fossilized infection not only documents the first occurrence of such a respiratory infection in a dinosaur, but it also has important anatomical implications for the respiratory system of sauropod dinosaurs.

“This fossil infection in Dolly not only helps us trace the evolutionary history of respiratory-related diseases back in time, but it also gives us a better understanding of what kinds of diseases dinosaurs were susceptible to,” Woodruff said.

“This would have been a remarkably, visibly sick sauropod,” Wolff said. “We always think of dinosaurs as big and tough, but they got sick. They had respiratory illnesses like birds do today, in fact, maybe even the same devastating infections in some cases.”

The researchers believe that if Dolly had been infected with an aspergillosis-like respiratory infection, she would have experienced flu or pneumonia-like symptoms such as weight loss, coughing, fever, and breathing difficulties. Because aspergillosis can be fatal in birds if left untreated, a potentially similar infection in Dolly could have resulted in the animal’s death.

“We must continue to learn more about ancient diseases. If we look hard enough, we might learn more about the evolution of immunity and infectious disease,” Wolff said. “When we collaborate across multiple specialties – veterinarians, anatomists, paleontologists, paleopathologists, and radiologists – we can get a more complete picture of ancient disease.”

Dinosaurs fascinate people more than almost any other group of fossil animals, and many open questions about dinosaur biology pique the public’s interest. How quickly could dinosaurs run? Were they hot-blooded? Do they have the ability to fly if they have feathers? These inquiries center on dinosaur metabolism and movement, both of which are inextricably linked with the respiratory system. Breathing — the ability to take in air, extract oxygen from it, and then expel it from the body along with waste carbon dioxide — establishes a fundamental upper limit on how much activity an organism is capable of.