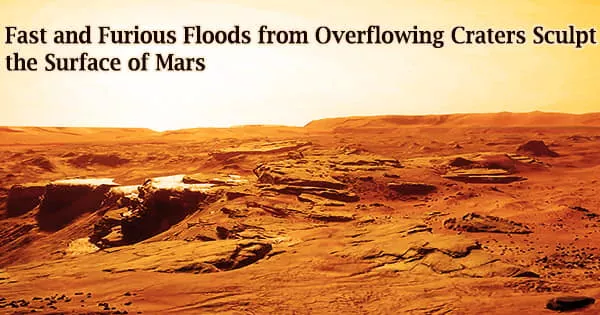

River erosion occurs slowly on Earth most of the time. But a new study headed by researchers at The University of Texas in Austin found that on Mars, enormous floods from overflowing crater lakes played a disproportionately large role in shaping the Martian surface, sculpting deep chasms and moving immense amounts of debris.

According to the study, which was released on September 29, 2021, in Nature, the floods, which most likely only lasted a few weeks, removed more than enough silt to fill Lake Superior and Lake Ontario to capacity.

“If we think about how sediment was being moved across the landscape on ancient Mars, lake breach floods were a really important process globally,” said lead author Tim Goudge, an assistant professor at the UT Jackson School of Geosciences. “And this is a bit of a surprising result because they’ve been thought of as one-off anomalies for so long.”

When Mars’ surface was covered in liquid water billions of years ago, crater lakes were prevalent. A small sea’s worth of water may fit into some craters.

However, when the water level rose to an unmanageable level, it would overflow the crater’s edge and cause catastrophic floods that left river valleys in its wake. Goudge led a 2019 study that found that these events happened rapidly.

Scientists have been able to examine the remains of shattered Martian crater lakes thanks to remote sensing photos captured by satellites orbiting Mars. Goudge noted that most research on the crater lakes and associated river valleys has been done on an individual basis. This is the first investigation into the overall impact of the 262 breached lakes throughout the surface of Mars.

Reviewing an existing list of river valleys on Mars, the research involved categorizing the valleys into two groups: those that began at the edge of craters, indicating they formed during a lake breach flood, and those that began elsewhere on the landscape, indicating a more gradual formation over time.

If we think about how sediment was being moved across the landscape on ancient Mars, lake breach floods were a really important process globally. And this is a bit of a surprising result because they’ve been thought of as one-off anomalies for so long.

Tim Goudge

The researchers then compared the depth, length, and volume of the various valley types and discovered that river valleys created by crater lake breaches far outperform their size, eroding away nearly a quarter of the river valley volume on the Red Planet despite only making up 3% of the total valley length.

“This discrepancy is accounted for by the fact that outlet canyons are significantly deeper than other valleys,” said study co-author Alexander Morgan, a research scientist at the Planetary Science Institute.

The median depth of a breach river valley is 559 feet (170.5 meters), which is more than twice as deep as other river valleys formed more gradually through time, which have a median depth of roughly 254 feet (77.5 meters).

Furthermore, despite the chasms’ sudden geologic appearance, the surrounding landscape might have been altered in a long-lasting way. According to the study, the breaches may have influenced the creation of other surrounding river basins by deeply scouring canyons.

According to the authors, this is a potential other explanation for the distinctive topography of the Martian river valley, which is typically attributed to climate. The research shows that lake breach river valleys were crucial in forming the Martian terrain, but Goudge added that it also teaches us about expectations.

Most craters on Earth have been eliminated by geology, which in most cases makes river erosion a gradual and constant process. On other worlds, though, it might not operate in the same manner.

“When you fill the craters with water, it’s a lot of stored energy there to be released,” Goudge said. “It makes sense that Mars might tip, in this case, toward being shaped by catastrophism more than the Earth.”

Gaia Stucky de Quay, a postdoctoral researcher at the Jackson School, and Caleb Fassett, a planetary scientist at the NASA Marshall Space Flight Center, are the study’s additional co-authors. (NASA funded the research.)