Rather than weeds, antibiotics are typically designed to target and eliminate bacterial infections in humans and animals. Herbicides, on the other hand, are specifically designed to control or eliminate undesirable plant growth, such as weeds. These products are subjected to extensive testing and evaluation to ensure their safety and efficacy for agricultural use.

Future weed killers may soon be based on failed antibiotics. A molecule that was developed to treat tuberculosis but did not make it out of the lab as an antibiotic is now showing promise as a potent foe for weeds, which invade our gardens and cost farmers billions of dollars each year.

While the failed antibiotic was unsuitable for its intended purpose, researchers at the University of Adelaide discovered that by modifying its structure, the molecule became effective at killing two of Australia’s most troublesome weeds, annual ryegrass, and wild radish, without harming bacterial or human cells.

This discovery has the potential to change the agricultural industry forever. Many weeds are now resistant to currently available herbicides, costing farmers billions of dollars each year.

Dr Tatiana Soares da Costa

“This discovery has the potential to change the agricultural industry forever.” Many weeds are now resistant to currently available herbicides, costing farmers billions of dollars each year,” said lead researcher Dr. Tatiana Soares da Costa of the University of Adelaide’s Waite Research Institute.

“Using failed antibiotics as herbicides expedites the development of new, more effective weed killers that target damaging and invasive weeds that farmers find difficult to control.”

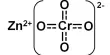

At the molecular level, researchers at the University’s Herbicide and Antibiotic Innovation Lab discovered similarities between bacterial superbugs and weeds. They took advantage of these similarities and were able to block the production of the amino acid lysine, which is required for weed growth, by chemically modifying the structure of a failed antibiotic.

“There are no commercially available herbicides on the market that work in this manner.” In fact, there have been few new herbicides with novel mechanisms of action that have entered the market in the last 40 years,” said Dr. Andrew Barrow, a postdoctoral researcher in Dr. Soares da Costa’s team at the University of Adelaide’s Waite Research Institute.

Weeds are estimated to cost the Australian agricultural industry more than $5 billion per year. Annual ryegrass, in particular, is one of the most serious and costly weeds in southern Australia.

“The shortcut strategy saves valuable time and resources, which could speed up the commercialization of much-needed new herbicides,” said Dr. Soares da Costa.

“It’s also worth noting that using failed antibiotics will not result in antibiotic resistance because the herbicidal molecules we discovered do not kill bacteria.” “They only affect weeds and have no effect on human cells,” she explained.

This discovery has the potential to benefit more than just farmers. According to the researchers, it could also lead to the development of new weed killers to target those pesky weeds that grow in our backyards and driveways.

“Our re-purposing approach has the potential to discover herbicides with broad applications that can kill a wide variety of weeds,” Dr. Barrow said.