An ancestral species is a common ancestor if it is shared as an ancestor by two or more descendant species. When we say a trait is identical by descent, we usually mean that a common ancestor shared that trait with more than one descendant species.

An international team has reconstructed the genome organization of the earliest common ancestor of all mammals. The reconstructed ancestral genome could aid in understanding the evolution of mammals as well as the conservation of modern animals. The earliest mammal ancestor most likely resembled the fossil animal “Morganucodon,” which lived around 200 million years ago. The research was published in the scientific journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Every modern mammal, from a platypus to a blue whale, is descended from a common ancestor who lived around 180 million years ago. We don’t know much about this animal, but an international team of scientists has now computationally reconstructed its genome.

“Our results have important implications for understanding the evolution of mammals and for conservation efforts,” says Harris Lewin, distinguished professor of evolution and ecology at the University of California, Davis, and senior author on the paper.

Our results have important implications for understanding the evolution of mammals and for conservation efforts. The findings will aid in understanding the genetics behind adaptations that have allowed mammals to thrive on a changing planet over the last 180 million years.

Harris Lewin

The researchers used high-quality genome sequences from 32 living species, representing 23 of the 26 known mammalian orders. Humans and chimps were among them, as were wombats and rabbits, manatees, domestic cattle, rhinos, bats, and pangolins. The chicken and Chinese alligator genomes were also used as comparison groups in the study. Some of these genomes are being generated as part of the Earth BioGenome Project and other large-scale biodiversity genome sequencing initiatives. The Earth BioGenome Project Working Group is chaired by Lewin.

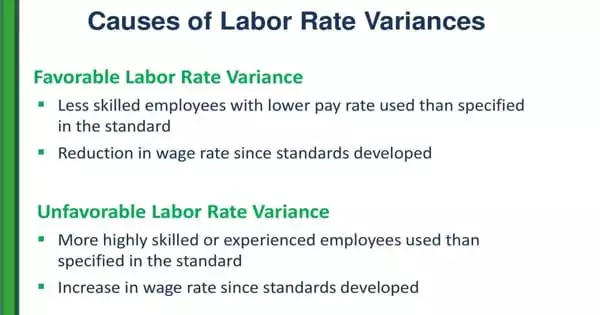

According to Joana Damas, first author of the study and a postdoctoral scientist at the UC Davis Genome Center, the mammal ancestor had 19 autosomal chromosomes, which control the inheritance of an organism’s characteristics other than those controlled by sex-linked chromosomes (these are paired in most cells, making 38 in total), plus two sex chromosomes. The researchers discovered 1,215 blocks of genes that appear on the same chromosome in the same order across all 32 genomes. These building blocks of all mammal genomes contain genes required for normal embryo development.

Chromosomes stable over 300 million years

The researchers discovered nine whole chromosomes or chromosome fragments in the mammal ancestor that have the same gene order as modern bird chromosomes.

“This remarkable discovery demonstrates the evolutionary stability of the order and orientation of genes on chromosomes over a time span of more than 320 million years,” Lewin says. Regions between these conserved blocks, on the other hand, contained more repetitive sequences and were more susceptible to breakages, rearrangements, and sequence duplications, all of which are major drivers of genome evolution.

“Ancestral genome reconstructions are critical to interpreting where and why selective pressures vary across genomes. This study establishes a clear relationship between chromatin architecture, gene regulation and linkage conservation,” says Professor William Murphy, Texas A&M University, who was not an author on the paper. “This provides the foundation for assessing the role of natural selection in chromosome evolution across the mammalian tree of life.”

The scientists were able to trace the ancestral chromosomes back to their common ancestor. They discovered that the rate of chromosome rearrangement varied across mammal lineages. For example, there was an acceleration in rearrangement in the ruminant lineage (leading to modern cattle, sheep, and deer) 66 million years ago, when an asteroid impact killed off the dinosaurs and led to the rise of mammals.

“The findings will aid in understanding the genetics behind adaptations that have allowed mammals to thrive on a changing planet over the last 180 million years,” says co-author Dr. Camilla Mazzoni, head of “Evolutionary and conservation genetics” at the Berlin Center for Genomics in Biodiversity Research and Research Group Leader in Evolutionary and Conservation Genomics at the Department of Evolutionary Genetics at Leibniz-IZW.