A variety of work and home-related issues, such as the lack of a work locker or a place to wash work clothing, can have an impact on the dangerous metal concentrations that workers track from their workplaces to their homes.

Toxic pollutants brought home accidentally from the workplace, exposing children and other family members, is a well-documented public health problem, however, the majority of research and interventions have focused on lead take-home exposure. Take-home exposures to other hazardous metals are even less well understood.

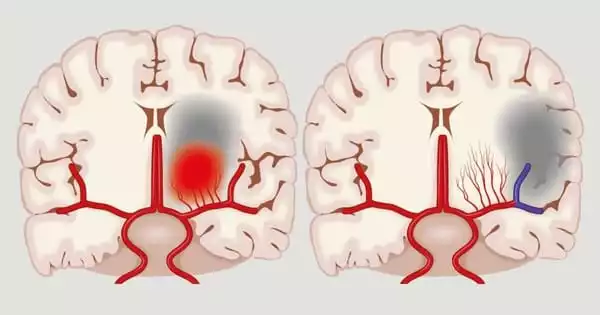

Individual metals and metal complexes, especially “heavy metals,” are toxic metals that have a severe impact on people’s health. This page discusses certain poisonous semi-metallic elements such as arsenic and selenium.

Many of these metals are required for life in extremely small levels. In larger quantities, however, they become toxic. They may accumulate in biological systems and provide a serious health risk.

Now, a new study lead by a Boston University School of Public Health (BUSPH) researcher shows that construction workers, in particular, are at significant risk of bringing a variety of additional dangerous metals into their homes by accident. The survey finds and counts the most metals 30 in the houses of construction workers to date.

Construction workers had greater amounts of arsenic, chromium, copper, manganese, nickel, and tin dust in their dwellings than janitors and auto mechanics, according to the findings, which were published in the journal Environmental Research.

Given the lack of policies and training in place to stop this contamination in high-exposure workplaces such as construction sites, it is inevitable that these toxic metals will migrate to the homes, families, and communities of exposed workers.

Dr. Diana Ceballos

Metal concentrations in the dust of employees’ homes are also affected by overlapping sociodemographic, occupational, and home-related characteristics, according to the study.

This new information emphasizes the need for more proactive and preventative actions at construction sites to limit these dangerous exposures.

“Given the lack of policies and training in place to stop this contamination in high-exposure workplaces such as construction sites, it is inevitable that these toxic metals will migrate to the homes, families, and communities of exposed workers,” says study lead and corresponding author Dr. Diana Ceballos, an assistant professor of environmental health and director of the Exposure Biology Research Laboratory at BUSPH.

“Many professions are exposed to toxic metals at work, but construction workers have a more difficult job implementing safe practices when leaving the worksite because of the type of transient outdoor environments where they work, and the lack of training on these topics.”

Ceballos and colleagues from BUSPH and Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health recruited 27 Greater Boston workers to participate in this pilot study from 2018 to 2019, focusing primarily on construction workers but also including janitorial and auto repair workers, to better understand the sources and predictors of take-home exposure to metals dust.

The researchers went to the workers’ homes and collected dust vacuum samples, gave them questionnaires about work and home-related practices that could affect exposure, and made other observations to assess the metal concentrations in their homes.

Higher levels of cadmium, chromium, copper, manganese, and nickel were linked to a variety of sociodemographic and work and home factors, including lower education, working in construction, not having a work locker to store clothes, mixing work and personal items, not having a place to launder clothes, not washing hands after work, and not changing clothes after work, according to the researchers.

Many construction workers, according to Ceballos, live in disadvantaged communities or inferior homes that may already contain dangerous metals, which exacerbates the problem.

“Given the complexity of these issues, we need interventions on all fronts not only policies but also resources and education for these families,” she says.