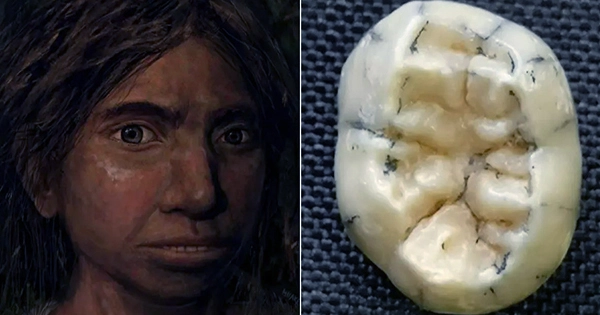

A tooth from a mystery “sister species” of humans known as the Denisovans has been unearthed in an unexpected location: Laos, Southeast Asia. This is the earliest evidence of early hominins in Southeast Asia, some 4,600 kilometers (2,850 miles) from the Denisova cave in Siberia, where the species’ first fossils were discovered. An international team of researchers describes the finding of a fossilized molar in Tam Ngu Hao 2, a newly discovered limestone cave in the Annamite Mountains of Laos, in an article published today in the journal Nature Communications.

“We’ve effectively unearthed the’smoking gun’ — this Denisovan tooth demonstrates they were formerly prevalent in the karst regions of Laos,” Flinders University Associate Professor Mike Morley said. The researchers had been seeking for Homo erectus and early modern Homo sapiens bones in the region, but the form and age of this tooth showed they were dealing with a Denisovan. Further examination revealed that the tooth belonged to a young female who died between the ages of 3.5 and 8.5.

Based on numerous dating procedures used to the surrounding silt, the teeth is thought to be between 164,000 and 131,000 years old, indicating that Denisovans may have traversed Asia at the period. Although physical relics of the species have hitherto eluded investigators, the genetic make-up of today’s human population strongly implies that Denisovans existed in Southeast Asia around this period. They appear to have found the proof after a lengthy search. Only five Denisovan remains have been officially verified: four in Siberia’s Denisova cave and one on the Tibetan Plateau.

Despite being so closely linked to Denisovans, we still know very little about them due to the scarcity of physical evidence (not to mention our historic interbreeding with them). Dr Fabrice Demeter, main study author and assistant professor of paleoanthropology at the University of Copenhagen, told IFLScience, “We don’t know what they looked like yet, [we] simply know about their genomes.”

“By 700,000 to 500,000 years ago, Denisovans and modern humans shared an ancestor,” he added. “Then the non-modern human branch separated again by 470,000 to 380,000 years ago, giving us Denisovans and Neanderthals.” “By 200,000 years ago, five separate species shared the same territory: H. erectus, H. floresiensis, H. luzonensis, H. sapiens, and the Denisovans, plus a sixth with the Western European Neanderthals.”

If verified, this recent discovery will give much-needed insight on this perplexing hominid species. Most importantly, it demonstrates that Denisovans inhabited a far larger area of Eurasia throughout the Late Pleistocene than previously thought, and that they were able to adapt to a wide range of settings. “We did not anticipate to uncover a Denisovan tooth in Laos,” Dr Demeter told IFLScience, “even if previous genetic research revealed that Denisovans and modern humans interacted in southern Asia during the Late Pleistocene.”

“Our research demonstrates that Denisovans lived in a diverse variety of settings and latitudes, adapting to harsh circumstances ranging from the icy Altai and Tibet to the tropical woods of Southeast Asia. Denisovans were accustomed to high altitude and cold conditions, according to genetic research and fossils, but now that we’ve discovered them, we know they also lived in warmer, more humid climes at low altitude.” The fossil tooth may have more to give as well. Dr. Demeter told IFLScience that scientists used isotope analysis on the enamel of the teeth to figure out what the Denisovans ate back when they lived in what is now Laos. The squad is waiting for the outcome with bated breath.