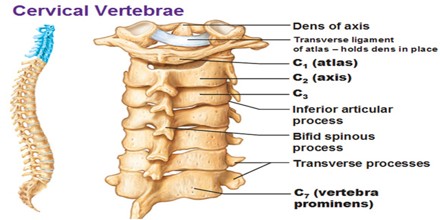

Cervical Vertebrae

Definition

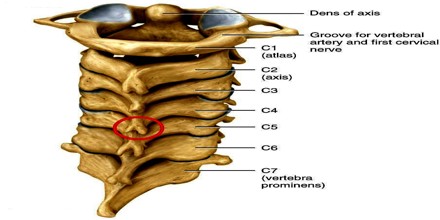

Cervical Vertebrae have cylindrical bones that lie in front of the spinal cord and stack up one on top of the other to make one continuous column of bones in the neck. The atlas is the first cervical vertebra (C1) and it forms the atlanto-occipital joint with the occipital bone, at the base of the skull. This joint allows the head to rock backwards and forwards. The second cervical vertebra is called the axis (C2) and the joint it forms with the atlas allows the head to rotate and tilt.

Thoracic vertebrae in all mammalian species are those vertebrae that also carry a pair of ribs, and lie caudal to the cervical vertebrae. Further caudally follow the lumbar vertebrae, which also belong to the trunk, but do not carry ribs. In reptiles, all trunk vertebrae carry ribs and are called dorsal vertebrae.

Cervical Vertebrae are curved towards the front, which is called the cervical lordosis. These vertebrae support the head, but also protect the spinal cord and its nerve roots that emerge from it, essentially spreading to innervate the neck and upper limbs. This section is made up of seven cervical vertebrae, with the first two forming the superior cervical spine, called the atlas and axis. These are the smallest of the true vertebrae, and can be readily distinguished from those of the thoracic or lumbar regions by the presence of a foramen (hole) in each transverse process, through which the vertebral artery passes.

Structure and Functions of Cervical Vertebrae

Cervical Vertebrae are stacked along the length of the neck to form a continuous column between the skull and the chest. The cervical vertebrae are numbered, with the first one (C1) closest to the skull and higher numbered vertebrae (C2–C7) proceeding away from the skull and down the spine.

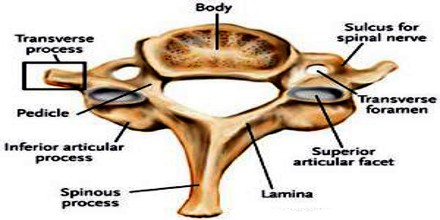

Each cervical vertebrae consists of a thin ring of bone, or vertebral arch, surrounding the vertebral and transverse foramina. The vertebral foramen is a large opening in the center of the vertebra that provides space for the spinal cord and its meninges as they pass through the neck. Flanking the vertebral foramen on each side are the much smaller transverse foramina. The transverse foramina surround the vertebral arteries and veins, which, along with the carotid arteries and jugular veins, have the vital job of carrying blood to and from the brain. The first, second, and seventh vertebrae are extraordinary, and are detailed later.

- The bodies of these four vertebrae are small and broader from side to side than from front to back.

- The pedicles are directed laterally and backward, and attach to the body midway between its upper and lower borders, so that the superior vertebral notch is as deep as the inferior, but it is, at the same time, narrower.

- The laminae are narrow, and thinner above than below; the vertebral foramen is large, and of a triangular form.

- The spinous process is short and bifid, the two divisions being often of unequal size. Because the spinous processes are so short, certain superficial muscles attach to the nuchal ligament rather than directly to the vertebrae; the nuchal ligament itself attaching to the spinous processes of C2–C7 and to the posterior tubercle of the atlas.

- The superior and inferior articular processes of cervical vertebrae have fused on either or both sides to form articular pillars, columns of bone that project laterally from the junction of the pedicle and lamina.

- The articular facets are flat and of an oval form: the superior face backward, upward, and slightly medially and the inferior face forward, downward, and slightly laterally.

- The transverse processes are each pierced by the foramen transversarium, which, in the upper six vertebrae, gives passage to the vertebral artery and vein, as well as a plexus of sympathetic nerves. Each process consists of an anterior and a posterior part.

Cervical Vertebrae also provide support to the head and neck, including supporting the muscles that move this region of the body. The muscles that attach to the vertebral processes provide posture to the head and neck throughout the day and have the greatest endurance of all of the body’s muscles. Finally, the many joints formed between the skull and cervical vertebrae provide incredible flexibility that allows the head and neck to rotate, flex, and extend.

The cervical spine is comparatively mobile, and some component of this movement is due to flexion and extension of the vertebral column itself. This movement between the atlas and occipital bone is often referred to as the “yes joint”, owing to its nature of being able to move the head in an up-and-down fashion. The movement of shaking or rotating the head left and right happens almost entirely at the joint between the atlas and the axis, the atlanto-axial joint. A small amount of rotation of the vertebral column itself contributes to the movement. This movement between the atlas and axis is often referred to as the “no joint”, owing to its nature of being able to rotate the head in a side-to-side fashion.

Reference: health.com.net, innerbody.com, hilaryking.net, wikipedia.