Introduction

These tutorials are designed to provide you with knowledge and skills to improve every aspect of your camera work. They begin at the absolute novice level and work through to professional operations.

They are also applicable to any type of camera work. It doesn’t matter whether you aspire to be an amateur movie maker or a career camera operator — the same basic principles and techniques apply to all.

To get the most out of these tutorials, you should have two things:

- Access to a video camera. You should know how to turn it on, load a tape, press record, etc. If you’re having trouble with these basic functions, refer to your camera manual or supplier.

- Patience. Camera work is a skill which requires lots of learning and practice.

It doesn’t really matter what sort of camera you use, but one with a good range of manual functions is preferable.

Although the only equipment you really need is a camera, if you’re serious you might want to consider buying a few extra toys. To get started the best accessory you can buy is a good tripod.

Next : Terminology

Terminology

It’s unavoidable — if you’re serious, you’ve got to know some jargon. Fortunately, it’s not too complicated. This page contains a few essential terms to get you started.

Shot: All video is made up of shots. A shot is basically from when you press record to when you stop recording. Like the individual photos which make up an album, the shots get put together to make a video.

Framing & Composition: The frame is the picture you see in the viewfinder (or on a monitor). Composition refers to the layout of everything within a picture frame — what the subject is, where it is in the frame, which way it’s facing/looking, the background, the foreground, lighting, etc.

When you “frame” a shot, you adjust the camera position and zoom lens until your shot has the desired composition.

There is a general set of rules in the video industry which describe how to frame different types of camera shots, such as the ones illustrated below .

VWS (Very Wide Shot) | WS (Wide Shot) | CU (Close Up) |

Transition: Shots are linked (edited) in a sequence to tell a larger story. The way in which any two shots are joined together is called the transition.

Usually this is a simple cut, in which one shot changes instantly to the next. More complex transitions include mixing, wipes and digital effects. A moving shot (e.g. pan) can also be thought of as a transition from one shot to a new one.

The transition is very important in camera work, and you need to think constantly about how every shot will fit in with the ones before and after it. The key is not so much how the transition is achieved technically, but how the composition of each shot fits together.

Here are few more important terms. They will be explained in greater detail later:

| Pan | Side-to-side camera movement. |

| Tilt | Up-and-down camera movement. |

| Zoom | In-and-out camera movement (i.e. closer and more distant). |

| Iris (Exposure) | The opening which lets light into the camera. A wider iris means more light and a brighter picture. |

| White balance | Adjusting the colours until they look natural and consistent. |

| Shutter | Analogous to the shutter in a still camera. |

| Audio | Sound which is recorded to go with the pictures. |

Next : Planning

Planning

This is the most important step, and perhaps the most difficult to master. It should be where most of your your energy is directed.

Camera work is only one skill in a larger process — the goal of which is usually to produce a completed video, TV program, or presentation of some kind. To be good at camera work, you must have a clear picture of the whole process, and some idea of what the finished product should look & sound like.

If there’s one thing that separates the amateurs from the pros, it’s that amateurs “point and shoot”, whereas pros “plan and shoot”. Obviously there are times when you don’t have time to prepare before having to record — sometimes the action begins unexpectedly, and you just have to go for it. In these cases, as far as possible, you plan as you go. It can’t be stressed enough — planning is everything.

For general camera work, you can divide your plan into two parts: The “Shoot Plan” and the “Shot Plan”.

Shoot Plan

In this case, the word shoot refers to a shooting session. If you think of everything you record as being part of a shoot, and have a plan for every shoot, then you’re well on the way to having better organised footage.

First of all, be clear about the purpose of every shoot. Generally speaking, everything you do should be working towards a larger plan. Exactly what this is will depend on many factors.

- If you’re making a feature film, then the long-term plan is to gather all the shots required by the script/storyboard.

- If you’re making home videos, the long-term plan might be to create a historical archive for future generations .

- If you’re making a one-off project (such as a wedding video), you still have to bear in mind the long-term implications for the shoot.

Planning means adopting an attitude in which you take control. When you get out your video camera, instead of thinking “This will look good on video” and starting to shoot whatever happens, think “What do I want this to look like on video?”. You then shoot (and if necessary, direct) the action to achieve your goal.

Plan the approximate length of the shoot: How much footage do you need to end up with, and how long will it take you to get it?

Have a checklist of equipment, which could include: camera; tripod; tapes; batteries/power supply; microphones and audio equipment; lights and stands; pens, log sheets and other paper work.

Planning to Edit

This is critical. If you think that this doesn’t applies to you, then you’re wrong. Everything you capture must be shot with editing in mind. There are two basic ways to edit: Post-production and in-camera.

- Post-production (or just “post”) editing means taking the shots you’ve recorded and re-assembling them later using editing equipment. This is how the professionals work — it gives you much greater flexibility when you’re shooting and much better finished results.

To do simple post editing, all you need is your camera, a VCR, and a few connecting leads. What it means for your shooting plan is that you can collect your shots in any order, and you can get as many shots as you like. At the editing stage, you discard unwanted shots and assemble the good ones however you like. This can be a time-consuming task (especially if you don’t have much editing gear), but it’s usually worth the effort. - In-Camera editing simply means that what you shoot is what you get — there is no post-production. The point here is that you’re still editing. You still must decide which shot goes where, and which shots you don’t need at all. The difference is that you’re making these edit decisions as you shoot, rather than in post. This isn’t easy, and it isn’t possible to get it right all of the time. It requires planning, foresight, and experience.

Note: There is one other situation which should be mentioned: the live multi-camera shoot. This is where a number of cameras are linked to a central vision mixer, and a director cuts between cameras (for example, a live sports presentation). In this case, you can think of the editing as being done in real time as the shoot happens.

Whichever method of editing you use, there are fundamental rules to follow. Since understanding these rules requires some knowledge of shot types and framing, we’ll leave them for now and come back to them later.

Shot Plan

Once you have a plan for your shooting session, you’re ready to begin planning individual shots.

First of all, have a reason for every shot. Ask yourself: “What am I trying to achieve with this shot? Is this shot even necessary? Have I already got a shot that’s essentially the same as this one? Is my audience going to care about this subject?”

Once you’re happy that you have a good reason to get the shot, think about the best way to get it. Consider different angles, framing, etc. The art of good composition takes time to master but with practice you will get there.

Ask yourself exactly what information you wish to convey to your audience through this shot, and make sure you capture it in a way that they will understand.

Take the time to get each shot right, especially if it’s an important one. If necessary (and if you’re editing in post), get a few different versions of the shot so you can choose the best one later.

Also, for post editing, leave at least 5 seconds of pictures at the beginning and end of each shot. This is required by editing equipment, and also acts as a safety buffer.

Finally, one more piece of advice: Before planning or shooting anything, imagine watching it completed.

Next : Camera Functions.

Camera Functions

Most domestic camcorders can do just about everything automatically. All you have to do is turn them on, point, and press record. In most situations this is fine, but automatic functions have some serious limitations. If you want to improve your camera work, you must learn to take control of your camera. This means using manual functions. In fact, professional cameras have very few automatic functions, and professional camera operators would never normally use auto-focus or auto-iris.

This is where most beginners ask “Why not? My auto-focus works fine, and my pictures seem to look okay.”

There are two answers:

- Although auto-functions usually perform well enough, there will be some situations they can’t cope with (e.g. bad lighting conditions). In these circumstances you may be faced with unusable footage unless you can take manual control. More commonly, your shots will be useable but poor quality (e.g. going in and out of focus).

- Your camera can’t know what you want. To get the best results or obtain a particular effect it is often necessary to over-ride auto-functions and go manual.

As you learn more about camera work you will begin to appreciate the better results gained through manual functions.

The most common camera operations are briefly explained below. Starting at the beginning, learn and practice one at a time, leaving the others on auto-function.

Zoom

This is the function which moves your point of view closer to, or further away from, the subject. The effect is similar to moving the camera closer or further away.

Note that the further you zoom in, the more difficult it is to keep the picture steady. In some cases you can move the camera closer to the subject and then zoom out so you have basically the same framing. For long zooms you should use a tripod.

Zooming is the function everyone loves. It’s easy and you can do lots with it, which is why it’s so over-used. The most common advice we give on using the zoom is use it less. It works well in moderation but too much zooming is tiring for the audience.

Focus

Auto-focus is strictly for amateurs. Unlike still photography, there is no way auto-focus can meet the needs of a serious video camera operator. Many people find manual focus difficult, but if you want to be any good at all, good focus control is essential.

Professional cameras usually have a manual focus ring at the front of the lens housing. Turn the ring clockwise for closer focus, anti-clockwise for more distant focus. Consumer cameras have different types of focus mechanisms — usually a small dial.

To obtain the best focus, zoom in as close as you can on the subject you wish to focus on, adjust the ring until the focus is sharp, then zoom out to the required framing.

Iris

This is an adjustable opening (aperture), which controls the amount of light coming through the lens (i.e. the “exposure”). As you open the iris, more light comes in and the picture appears brighter.

Professional cameras have an iris ring on the lens housing, which you turn clockwise to close and anticlockwise to open. Consumer-level cameras usually use either a dial or a set of buttons.

The rule of thumb for iris control is: Set your exposure for the subject. Other parts of the picture can be too bright or darks, as long as the subject is easy to see.

White Balance

White balance means colour balance. It’s a function which tells the camera what each colour should look like, by giving it a “true white” reference. If the camera knows what white looks like, then it will know what all other colours look like.

This function is normally done automatically by consumer-level cameras without the operator even being aware of it’s existence. It actually works very well in most situations, but there will be some conditions that the auto-white won’t like. In these situations the colours will seem wrong or unnatural.

To perform a white balance, point the camera at something matt (non-reflective) white in the same light as the subject, and frame it so that most or all of the picture is white. Set your focus and exposure, then press the “white balance” button (or throw the switch). There should be some indicator in the viewfinder which tells you when the white balance has completed. If it doesn’t work, try adjusting the iris, changing filters, or finding something else white to balance on.

You should do white balances regularly, especially when lighting conditions change (e.g. moving between indoors and outdoors).

Audio

Virtually all consumer-level cameras come with built-in microphones, usually hi-fi stereo. These work fine, and are all you need for most general work.

Getting better results with audio is actually quite difficult and is a whole subject in itself. We won’t go into it much here — you just need to be aware that audio is very important and shouldn’t be overlooked.

If you’re keen, try plugging an external microphone into the “mic input” socket of your camera (if it has one). There are two reasons why you might want to do this:

- You may have a mic which is more suited to the type of work you are doing than the camera’s built-in mic. Often, the better mic will simply be mounted on top of the camera.

- You might need to have the mic in a different position to the camera. For example, when covering a speech, the camera could be at the back of the room with a long audio lead running to the stage, where you have a mic mounted on the pedestal.

The level at which your audio is recorded is important. Most cameras have an “auto-gain control”, which adjusts the audio level automatically. Consumer-level cameras are usually set up like this, and it works well in most situations. If you have a manual audio level control, it’s a good idea to learn how to use it (more on this later).

If possible, try to keep the background (ambient) noise level more or less consistent. This adds smoothness to the flow of the production. Of course, some shots will require sudden changes in ambient audio for effect.

Listen to what people are saying and build it into the video. Try not to start and finish shots while someone is talking — there’s nothing worse than a video full of half-sentences.

Be very wary of background music while shooting — this can result is music that jumps every time the shot changes, like listening to a badly scratched record. If you can, turn the music right down or off.

One more thing… be careful of wind noise. Even the slightest breeze can ruin your audio. Many cameras have a “low-cut filter”, sometimes referred to as a “wind-noise filter” or something similar. These do help, but a better solution is to block the wind. You can use a purpose-designed wind sock, or try making one yourself.

Shutter

At the beginner level you don’t really need to use the shutter, but it deserves a quick mention. It has various applications, most notably for sports or fast-action footage. The main advantage is that individual frames appear sharper (critical for slow-motion replays). The main disadvantage is that motion appears more jerky.

The shutter can also be used to help control exposure.

Effects

Many consumer cameras come with a selection of built-in digital effects, such as digital still, mix, strobe, etc. These can be very cool, or they can be very clumsy and tacky. They require dedicated experimentation to get right. Like so many things in video, moderation is the key: use them if you have a good reason to, but don’t overdo it.

You should also be aware that almost every effect you can create with a camera can be done better with editing software. If at all possible, shoot your footage “dry” (without effects) and add effects later.

Remember: Although it is sometimes the more practical solution to use automatic features, as a general rule you should do as many camera operations manually as you can.

Next : Framing

Framing

Shots are all about composition. Rather than pointing the camera at the subject, you need to compose an image. As mentioned previously, framing is the process of creating composition.

Notes:

- Framing technique is very subjective. What one person finds dramatic, another may find pointless. What we’re looking at here are a few accepted industry guidelines which you should use as rules of thumb.

- The rules of framing video images are essentially the same as those for still photography.

Basic shot types

There is a general convention in the video industry which assigns names to the most common types of shots. The names and their exact meanings may vary, but the following examples give a rough guide to the standard descriptions. The point isn’t knowing the names of the shot types (although it’s very useful), as much as understanding their purposes.

Basic shots are referred to in terms relative to the subject. For example, a “close up” has to be a close up of something. A close up of a person could also be described as a wide shot of a face, or a very wide shot of a nose.

The subject in all of the following shots is a young girl standing in front of a country house.

| EWS (Extreme Wide Shot) In the EWS, the view is so far from the subject that she isn’t even visible. The point of this shot is to show the subject’s surroundings. The EWS is often used as an establishing shot — the first shot of a new scene, designed to show the audience where the action is taking place. | |

| VWS (Very Wide Shot) The VWS is much closer to the subject. She is (just) visible here, but the emphasis is still on placing her in her environment. This also works as an establishing shot. | |

| WS (Wide Shot) In the WS, the subject takes up the full frame. In this case, the girl’s feet are almost at the bottom of frame, and her head is almost at the top. Obviously the subject doesn’t take up the whole width and height of the frame, since this is as close as we can get without losing any part of her. The small amount of room above and below the subject can be thought of as safety room — you don’t want to be cutting the top of the head off. It would also look uncomfortable if her feet and head were exactly at the top and bottom of frame. | |

| MS (Mid Shot) The MS shows some part of the subject in more detail, whilst still showing enough for the audience to feel as if they were looking at the whole subject. In fact, this is an approximation of how you would see a person “in the flesh” if you were having a casual conversation. You wouldn’t be paying any attention to their lower body, so that part of the picture is unnecessary. | |

| MCU (Medium Close Up) Half way between a MS and a CU. This shot shows the face more clearly, without getting uncomfortably close. | |

| CU (Close Up) In the CU, a certain feature or part of the subject takes up the whole frame. A close up of a person usually means a close up of their face. | |

| ECU (Extreme Close Up) The ECU gets right in and shows extreme detail. For people, the ECU is used to convey emotion. | |

| CA (Cutaway) A cutaway is a shot that’s usually of something other than the current action. It could be a different subject (e.g. this cat), a CU of a different part of the subject (e.g. a CU of the subject’s hands), or just about anything else. The CA is used as a “buffer” between shots (to help the editing process), or to add interest/information. |

Some Rules of Framing

- Look for horizontal and vertical lines in the frame (e.g. the horizon, poles, etc). Make sure the horizontals are level, and the verticals are straight up and down (unless of course you’re purposely going for a tilted effect).

- The rule of thirds. This rule divides the frame into nine sections, as in the first frame below. Points (or lines) of interest should occur at 1/3 or 2/3 of the way up (or across) the frame, rather than in the centre.

- “Headroom”, “looking room”, and “leading room”. These terms refer to the amount of room in the frame which is strategically left empty. The shot of the baby crawling has some leading room for him to crawl into, and the shot of his mother has some looking room for her to look into. Without this empty space, the framing will look uncomfortable.

Headroom is the amount of space between the top of the subject’s head and the top of the frame. A common mistake in amateur video is to have far too much headroom, which doesn’t look good and wastes frame space. In any “person shot” tighter than a MS, there should be very little headroom.

- Everything in your frame is important, not just the subject. What does the background look like? What’s the lighting like? Is there anything in the frame which is going to be distracting, or disrupt the continuity of the video?

Pay attention to the edges of your frame. Avoid having half objects in frame, especially people (showing half of someone’s face is very unflattering). Also try not to cut people of at the joints — the bottom of the frame can cut across a person’s stomach, but not their knees. It just doesn’t look right.

Once you’re comfortable with the do’s and don’ts, you can become more creative. Think about the best way to convey the meaning of the shot. If it’s a baby crawling, get down on the floor and see it from a baby’s point-of-view (POV). If it’s a football game, maybe you need to get up high to see all the action.

Look for interesting and unusual shots. Most of your shots will probably be quite “straight”; that is, normal shots from approximate adult eye-level. Try mixing in a few variations. Different angles and different camera positions can make all the difference. For example; a shot can become much more dramatic if shot from a low point. On the other hand, a new and interesting perspective can be obtained by looking straight down on the scene. Be aware that looking up at a person can make them appear more imposing, whereas looking down at a person can diminish them.

Watch TV and movies, and notice the shots which stand out. There’s a reason why they stand out — it’s all about camera positioning and frame composition. Experiment all the time.

Basic Camera Moves

As with camera framing, there are standard descriptions for the basic camera moves. These are the main ones:

Pan: The framing moves left & right, with no vertical movement.

Tilt: The framing moves up & down, with no horizontal movement.

Zoom: In & out, appearing as if the camera is moving closer to or further away from the subject. (There is a difference between zooming and moving the camera in and out, though. There’ll be more about that in the intermediate tutorial.)

When a shot zooms in closer to the subject, it is said to be getting “tighter”. As the shot zooms out, it is getting “looser”.

Follow: Any sort of shot when you are holding the camera (or have it mounted on your shoulder), and you follow the action whilst walking. Hard to keep steady, but very effective when done well.

Note: Most camera moves are a combination of these basic moves. For example, when you’re zooming in, unless your subject is in the exact centre of frame, you’ll have to pan and/or tilt at the same time to end up where you want to be.

Next : Shooting Technique

Shooting Technique

Position yourself and your camera. If you’re using a tripod, make sure it’s stable and level (unless you have a reason for it to be tilted). If the tripod has a spirit level, check it.

If you’re going to be panning and/or tilting, make sure that you’ll be comfortably positioned throughout the whole move. You don’t want to start a pan, then realise you can’t reach around far enough to get the end of it. If it’s going to be difficult, you’re better off finding the position which is most comfortable at the end of the move, so that you start in the more awkward position and become more comfortable as you complete the move.

If the tripod head doesn’t have a bowl (this includes most cheaper tripods), it’s very important to check that the framing still looks level as you pan – it may be okay in one direction but become horribly slanted as you pan left and right.

If you’re not using a tripod, stabilise yourself and your camera as best you can. Keep your arms and elbows close to your body (you can use your arms as “braces” against your torso). Breathe steadily. For static shots, place your feet at shoulder width (if you’re standing), or try bracing yourself against some solid object (furniture, walls, or anything).

Frame your shot. Then do a quick mental check: white balance; focus; iris; framing (vertical and horizontal lines, background, etc.).

Think about your audio. Audio is just as important as vision, so don’t forget about it.

Press “record”. Once you’re recording, make sure that you are actually recording. There’s no worse frustration than realising that you were accidentally recording all the time you were setting the shot up, then stopped recording when you thought you were starting.

Many cameras have a tape “roll-in time”, which means that there is a delay between the time you press record and when the camera begins recording. Do some tests and find out what your camera’s roll-in time is, so you can then compensate for it.

Keep checking the status displays in the viewfinder. Learn what all the indicators mean — they can give you valuable information.

Use both eyes. A valuable skill is the ability to use one eye to look through the viewfinder, and the other eye to watch your surroundings. It takes a while to get used to it, but it means that you can walk around while shooting without tripping over, as well as keeping an eye out for where the action is happening. It’s also easier on your eyes during long shoots.

Learn to walk backwards. Have someone place their hand in the middle of your back and guide you. These shots can look great.

You’ll often see television presenters walking and talking, as the camera operator walks backwards shooting them.

Keep thinking “Framing…Audio…” As long as you’re recording, think about how the frame composition is changing, and what’s happening to the sound.

Press “record stop” before moving. Just as in still photography, you should wait until one second after you’ve finished recording (or taken the photo) before you move. Too many home videos end every shot with a jerky movement as the operator hits the stop button.

That’s all there is to it! Finally, here’s a few more tips to finish off with…

Be diplomatic while shooting. Think about the people you’re shooting. Remember that people are often uncomfortable about being filmed, so try to be discreet and unobtrusive (for example, you might want to position yourself some distance from the subjects and zoom in on them, rather than being “in their faces”).

Many people find the red recording light on the camera intimidating, and freeze whenever they see it. Try covering the light with a piece of tape to alleviate this problem.

Learn to judge when it’s worth making a nuisance of yourself for the sake of the shot, and when it’s not. If it’s an important shot, it might be necessary to inconvenience a few people to get it right. But if you’re going to make enemies over something that doesn’t matter, forget it and move on.

Use the “date/time stamp” feature sparingly. It’s unnecessary to have the time and date displayed throughout your video, and it looks cheap. If you must have it there, bring it up for a few seconds, then get rid of it.

Modern digital cameras have the ability to show or hide this display at any time after recording.

Be prepared to experiment. Think about some of the things you’d like to try doing, then try them at a time that doesn’t matter (i.e. don’t experiment while shooting a wedding). Most new techniques take practice and experimentation to achieve success, and good camera work requires experience.

Camera Angles

The term camera angle means slightly different things to different people but it always refers to the way a shot is composed. Some people use it to include all camera shot types, others use it to specifically mean the angle between the camera and the subject. We will concentrate on the literal interpretation of camera angles, that is, the angle of the camera relative to the subject.

Eye-Level

This is the most common view, being the real-world angle that we are all used to. It shows subjects as we would expect to see them in real life. It is a fairly neutral shot.

High Angle

A high angle shows the subject from above, i.e. the camera is angled down towards the subject. This has the effect of diminishing the subject, making them appear less powerful, less significant or even submissive.

Low Angle

This shows the subject from below, giving them the impression of being more powerful or dominant.

Bird’s Eye

The scene is shown from directly above. This is a completely different and somewhat unnatural point of view which can be used for dramatic effect or for showing a different spatial perspective.

In drama it can be used to show the positions and motions of different characters and objects, enabling the viewer to see things the characters can’t.

The bird’s-eye view is also very useful in sports, documentaries, etc.

Slanted

Also known as a dutch tilt, this is where the camera is purposely tilted to one side so the horizon is on an angle. This creates an interesting and dramatic effect. Famous examples include Carol Reed’s The Third Man, Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane and the Batman series.

Dutch tilts are also popular in MTV-style video production, where unusual angles and lots of camera movement play a big part.

Shot Types

There is a convention in the video, film and television industries which assigns names and guidelines to common types of shots, framing and picture composition. The list below briefly describes the most common shot types. Note that the exact terminology may vary between production environments but the basic principles are the same.

Click the images for more details. See below for more information and related tutorials.

EWS (Extreme Wide Shot) The view is so far from the subject that she isn’t even visible. This is often used as an establishing shot. | VWS (Very Wide Shot) The subject is visible (barely), but the emphasis is still on placing her in her environment. | WS (Wide Shot) The subject takes up the full frame, or at least as much as possible. The same as a long shot. |

MS (Mid Shot) Shows some part of the subject in more detail whilst still giving an impression of the whole subject. | MCU (Medium Close Up) Half way between a MS and a CU. | CU (Close Up) A certain feature or part of the subject takes up the whole frame. |

ECU (Extreme Close Up) The ECU gets right in and shows extreme detail. | CA (Cutaway) A shot of something other than the current action. | Cut-In Shows some part of the subject in detail. |

Two-Shot A comfortable shot of two people, framed similarly to a mid shot. | (OSS) Over-the-Shoulder Shot Looking from behind a person at the subject. | Noddy Shot Usually refers to a shot of the interviewer listening and reacting to the subject, although noddies can be used in drama and other situations. |

Point-of-View Shot (POV) Shows a view from the subject’s perspective. | Weather Shot The subject is the weather, usually the sky. Can be used for other purposes. | |

Camera Moves

This page outlines the standard types of camera movement in film and video. In the real world, many camera moves use a combination of these techniques simultaneously.

| Crab | A less-common term for tracking or trucking. |

| Dolly | The camera is mounted on a cart which travels along tracks for a very smooth movement. Also known as a tracking shot or trucking shot. |

| Dolly Zoom | A technique in which the camera moves closer or further from the subject while simultaneously adjusting the zoom angle to keep the subject the same size in the frame. |

| Follow | The camera physically follows the subject at a more or less constant distance. |

| Pan | Horizontal movement, left and right. |

| Pedestal (Ped) | Moving the camera position vertically with respect to the subject. |

| Tilt | Vertical movement of the camera angle, i.e. pointing the camera up and down (as opposed to moving the whole camera up and down). |

| Track | Roughly synonymous with the dolly shot, but often defined more specifically as movement which stays a constant distance from the action, especially side-to-side movement. |

| Truck | Another term for tracking or dollying. |

| Zoom | Technically this isn’t a camera move, but a change in the lens focal length with gives the illusion of moving the camera closer or further away. |

Dolly Shot

A dolly is a cart which travels along tracks. The camera is mounted on the dolly and records the shot as it moves. Dolly shots have a number of applications and can provide very dramatic footage.

In many circles a dolly shot is also known as a tracking shot or trucking shot. However some professionals prefer the more rigid terminology which defines dolly as in-and-out movement (i.e. closer/further away from the subject), while tracking means side-to-side movement.

Most dollies have a lever to allow for vertical movement as well (known as a pedestal move). In some cases a crane is mounted on the dolly for additional height and flexibility. A shot which moves vertically while simultaneously tracking is called a compound shot.

Some dollies can also operate without tracks. This provides the greatest degree of movement, assuming of course that a suitable surface is available. Special dollies are available for location work, and are designed to work with common constraints such as doorway width.

Dollies are operated by a dolly grip. In the world of big-budget movie making, good dolly grips command a lot of respect and earning power.

The venerable dolly faced serious competition when the Steadicam was invented. Most shots previously only possible with a dolly could now be done with the more versatile Steadicam. However dollies are still preferred for many shots, especially those that require a high degree of precision.

Dolly Zoom

A dolly zoom is a cinematic technique in which the camera moves closer or further from the subject while simultaneously adjusting the zoom angle to keep the subject the same size in the frame. The effect is that the subject appears stationary while the background size changes (this is called perspective distortion).

In the first example pictured, the camera is positioned close to the subject and the lens is zoomed out. In the second shot, the camera is several metres further back and the lens is zoomed in.

The Effect

Dolly zooms create an unnatural effect — this is something your eyes would never normally see. Many people comment on the shot after seeing it for the first time, e.g. “That was weird” or “What just happened there?”.

The exact effect depends on the direction of camera movement. If the camera moves closer, the background seems to grow and become dominant. If the camera moves further away, the foreground subject is emphasized and becomes dominant.

The effect is quite emotional and is often used to convey sudden realisation, reaction to a dramatic event, etc.

History

Invention of the dolly zoom is credited to cameraman Irmin Roberts. The technique was made famous by Alfred Hitchcock (Vertigo being the best-known example), and was used by Steven Spielberg in Jaws and ET. Many other directors have used the technique, which brings us to an important warning…

Warning

The dolly zoom is often over-used by junior directors. Many film critics see it as a cliché, so be very careful before you use this technique.

Other Terminology

The dolly zoom is also known as:

- Hitchcock zoom

- Vertigo zoom or vertigo effect

- Jaws shot

- Trombone shot

- Zolly or zido

- Telescoping

- Contra-zoom

- Reverse tracking

- Zoom in/dolly out (or vice versa)

Follow Shot

The Follow shot is fairly self-explanatory. It simply means that the camera follows the subject ot action. The following distance is usually kept more or less constant.

The movement can be achieved by dollying or tracking, although in many cases a Steadicam is the most practical option. Hand-held follow-shots are quite achievable in many situations but are not generally suited to feature film cinematography.

Camera Pan

A pan is a horizontal camera movement in which the camera moves left and right about a central axis. This is a swiveling movement, i.e. mounted in a fixed location on a tripod or shoulder, rather than a dolly-like movement in which the entire mounting system moves.

To create a smooth pan it’s a good idea to practice the movement first. If you need to move or stretch your body during the move, it helps to position yourself so you end up in the more comfortable position. In other words you should become more comfortable as the move progresses rather than less comfortable.

Pedestal Shot

A pedestal shot means moving the camera vertically with respect to the subject. This is often referred to as “pedding” the camera up or down.

The term comes from the type of camera support known as a pedestal (pictured right). Pedestals are used in studio settings and provide a great deal of flexibility as well as very smooth movement. Unlike standard tripods, pedestals have the ability to move the camera in any direction (left, right, up, down).

Note that a pedestal move is different to a camera tilt, which means the camera is in the same position but tilts the angle of view up and down. In a ped movement, the whole camera is moving, not just the angle of view.

In reality, like most camera moves, the pedestal move is often a combination of moves. For example, pedding while simultaneously panning and/or tilting.

Camera Tilt

A tilt is a vertical camera movement in which the camera points up or down from a stationary location. For example, if you mount a camera on your shoulder and nod it up and down, you are tilting the camera.

Tilting is less common than panning because that’s the way humans work — we look left and right more often than we look up and down.

The tilt should not be confused with the Dutch Tilt which means a deliberately slanted camera angle.

A variation of the tilt is the pedestal shot, in which the whole camera moves up or down.

Tracking Shot

The term tracking shot is widely considered to be synonymous with dolly shot; that is, a shot in which the camera is mounted on a cart which travels along tracks.

However there are a few variations of both definitions. Tracking is often more narrowly defined as movement parallel to the action, or at least at a constant distance (e.g. the camera which travels alongside the race track in track & field events). Dollying is often defined as moving closer to or further away from the action.

Some definitions specify that tracking shots use physical tracks, others consider tracking to include hand-held walking shots, Steadicam shots, etc.

Zoom Shot

A zoom is technically not a camera move as it does not require the camera itself to move at all. Zooming means altering the focal length of the lens to give the illusion of moving closer to or further away from the action.

The effect is not quite the same though. Zooming is effectively magnifying a part of the image, while moving the camera creates a difference in perspective — background objects appear to change in relation to foreground objects. This is sometimes used for creative effect in the dolly zoom.

Zooming is an easy-to-use but hard-to-get-right feature of most cameras. It is arguably the most misused of all camera functions.

Pickup Shots

Pickup shots are shots or scenes recorded after principal photography has concluded.

In some cases pickup shots are specifically planned. For example, on a film set, a scene may be filmed one day with the major actors and then the next day is devoted to pickup shots which do not require the actors. These shots could include close-ups of props, different angles in which the actors are not recognisable, etc.

In other cases pickup shots are unplanned shots which are needed to fix editing problems, re-shoot scenes for better quality, etc. As a contingency, time is usually allocated for pickup shots as part of the production plan.

Contrast Ratio for Cameras

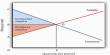

In video and film work it is important to understand what sort of contrast ratio your camera is able to reproduce. A high contrast ratio means that brighter and darker areas of the image will be recorded with more accuracy and apparent detail.

Most people don’t need to know the actual specifications but video makers need to be aware that video has a relatively low contrast ratio. If an image includes extreme light and dark, the camera will struggle to reproduce both. Bright areas will appear over-exposed and dark areas will appear “crushed” (all black, lacking detail).

The example on the right illustrates a common problem for sports coverage in stadiums — the difference between the sunlit areas and the shadows is significant.

The best way to minimize problems with contrast ratio is to avoid having very bright and very dark objects in frame at the same time. When dealing with human subjects it makes sense to avoid white and black clothing. Also, be wary of caps and sunglasses in strong light — they can create terrible over-contrast on the face.

If you can’t alter the framing, either add lighting to the dark areas or filter the bright areas.

When all else fails, the standard approach is to expose for the subject. If some parts of the picture are too bright or too dark it’s not the end of the world — people are used to seeing this.

Note: Film cameras generally perform better than video, but still do not reproduce the same range that the human eye would see.

Video Camera Focus

The ability to manually focus your camera is a critical skill at any level of video production. This page shows you the basics — at the end of the page you can choose to continue and learn more advanced focus techniques.

Note: Manual focus is so important that most professional cameras don’t even have an auto-focus feature.

Some Focus Jargon

| Soft: | Out of focus |

| Sharp: | In focus |

| Depth of Field: | The range of distances from the lens at which an acceptably sharp focus can be obtained |

| Pull focus: | Adjust the focus to a different point during a shot |

How to Use the Manual Focus

First of all, locate the focus control. Professional cameras usually have a manual focus ring near the front of the lens housing. Consumer-level cameras usually have a small dial (Note: you may need to select “manual focus” from the menu).

- Make sure the camera is set to manual focus.

- Zoom in as tight as you can on the subject you wish to focus on.

- Adjust the focus ring until the picture is sharp. Turn the ring clockwise for closer focus, anti-clockwise for more distant focus.

- Zoom out to the required framing — the picture should stay nice and sharp.

- If the picture loses focus when zoomed out, check the back-focus and make sure the macro focus is not engaged.

If you need to adjust your focus on the fly (for example, you’re in the middle of shooting the Prime Minister’s speech when you realise her face is soft), it helps to know which way to turn the focus ring. If you go the wrong way and defocus more, even if you correct yourself quickly you’ve drawn attention to your camera work. Try comparing the background and foreground focus. If the background is sharper than the subject, then you need to pull focus to a closer point (and vice versa).

Note: You will usually find the sharpest focus occurs at about the middle iris position.

Difficult Focus Conditions

You’ll notice that focusing is more difficult in certain conditions. Basically, the more light coming through the lens, the easier it is to focus. Obviously it will be more difficult to focus in very low light. If you’re really struggling with low-light focus, and you can’t add more lighting, try these things:

- Make sure your shutter is turned off.

- If your camera has a filter wheel, make sure you’re using the correct low-light filter. Remove any add-on filters.

- If your camera has a digital gain function, try adding a little gain (note: this compromises picture quality).

- Stay zoomed as wide as possible. If your lens has a 2X extender, make sure it’s on 1X.

Video Camera Iris

The iris is an adjustable opening (aperture), which controls the amount of light coming through the lens (ie. the “exposure”). The video camera iris works in basically the same way as a still camera iris — as you open the iris, more light comes in and the picture appears brighter. The difference is that with video cameras, the picture in the viewfinder changes brightness as the iris is adjusted. For this tutorial, we’ll be setting exposure by eye; that is, adjusting the iris until the exposure looks right in the viewfinder (as opposed to using a light meter).

- Professional cameras have an iris ring on the lens housing, which you turn clockwise to close and anticlockwise to open.

- Consumer-level cameras usually use either a dial or a set of buttons. You will probably need to select manual iris from the menu (see your manual for details).

The Correct Exposure

Before using your manual iris, you need to know what the correct exposure looks like in your viewfinder (note: if your camera has the option to adjust viewfinder settings, you’ll need to do that first). A good start is to set your camera on auto-iris and frame a shot with nice, even lighting. Notice how bright the picture is, then set the iris to manual. Most cameras will retain the same exposure as set by the auto-function, which you can adjust from there as you go. Open and close the iris, then try to set the exposure where it was before.

Always set your iris so that the subject appears correctly exposed. This may mean that other parts of the picture are too bright or too dark, but the subject is usually more important.

Professional cameras have an additional feature called zebra stripes which can help you to judge exposure.

Practice is the only way to get exposure right. Record a number of shots in different light conditions, then play them back and see how good your exposure was. Remember, if you’re not sure about your exposure, try flicking the iris to auto and see what the camera thinks, then go back to manual. In time, you’ll come to trust yourself more than the auto-iris.

Backlight

A common difficulty with exposure is what to do in uneven lighting situations. The “strong backlight” scenario is a headache — this is where your subject is set against a much brighter background, as in the pictures below…

| In the first example, the camera is set to auto-iris. The camera adjusts the exposure for the strong backlight, which leaves the subject as a silhouette. Some cameras have a “backlight” feature which helps with this problem, but it won’t work as well as manual iris control.Assuming that you can’t change your framing or add more lighting to the subject, the only option is to open the iris until the subject is exposed correctly. This will mean the background is too bright, but it’s better than the subject being too dark. In the second example, the manual iris is opened until the subject is correctly exposed. Although this is still far from ideal exposure, it’s an improvement on the silhouette effect. In fact this situation is quite common — on television you’ll often see an outside window which looks too bright, but you don’t usually notice because you’re watching the subject inside. | |

Remember, the rule of thumb for iris control is: Set your exposure for the subject. Everything else is secondary.

Video Camera White Balance

White balance basically means colour balance. It is a function which gives the camera a reference to “true white” — it tells the camera what the colour white looks like, so the camera will record it correctly. Since white light is the sum of all other colours, the camera will then display all colours correctly.

Incorrect white balance shows up as pictures with orange or blue tints, as demonstrated by the following examples:

|

|

|

Most consumer-level camcorders have an “auto-white balance” feature, and this is how most amateurs operate. The camera performs it’s own white balance without any input from the operator. In fact, very few home-video users are aware of it’s existence. Unfortunately, the auto-white balance is not particularly reliable and it is usually preferable to perform this function manually.

Terminology

To confuse the issue, the term “automatic white balance” has two different interpretations. On consumer-level cameras, it means completely automatic. On professional-level cameras, it can mean the white balance operation as described below (which is actually quite manual). This is because in professional situations, a “manual white balance” can mean altering colours using specialised vision processing equipment.

The terminology we use at mediacollege.com is as follows:

“Auto-white” means the completely automatic function (no user input at all).

“Manual-white” means the operation described below.

“Colour correction” means any other method of adjusting colours.

How to Perform a Manual White Balance

You should perform this procedure at the beginning of every shoot, and every time the lighting conditions change. It is especially important to re-white balance when moving between indoors and outdoors, and between rooms lit by different kinds of lights. During early morning and late evening, the daylight colour changes quickly and significantly (although your eyes don’t notice, your camera will). Do regular white balances during these periods.

You will need:

- A camera with a manual white-balance function. There should be a “white balance” button or switch on your camera.

- If your camera has a filter wheel (or if you use add-on filters), make sure you are using the correct filter for the lighting conditions.

- Point your camera to a pure white subject, so that most of what you’re seeing in the viewfinder is white. Opinions vary on just how much white needs to be in the frame – but we’ve found that about 50-80% of the frame should be fine (Sony recommends 80% of frame width). The subject should be fairly matte, that is, non-reflective.

- Set your exposure and focus.

- Activate the white balance by pressing the button or throwing the switch. The camera may take a few seconds to complete the operation, after which you should get a message (or icon) in the viewfinder.

Hopefully this will be telling you that the white balance has succeeded – in this case, the camera will retain it’s current colour balance until another white balance is performed.

If the viewfinder message is that the white balance has failed, then you need to find out why. A good camera will give you a clue such as “colour temperature too high” (in which case change filters). Also try opening or closing the iris a little.

Note: Advanced camera operators occasionally trick the camera into reading an inaccurate white balance, in order to makethe pictures appear warmer (more orange) or cooler (more blue). We’ll look at this technique in a later tutorial.

Crossing the Line (Reverse Cut)

Crossing the line is a very important concept in video and film production. It refers to an imaginary line which cuts through the middle of the scene, from side to side with respect to the camera. Crossing the line changes the viewer’s perspective in such as way that it causes disorientation and confusion. For this reason, crossing the line is something to be avoided.

| In this example the camera is located to the subject’s left. The imaginary line is shown in red.The resulting shot shows the subject walking from right to left, establishing the viewer’s position and orientation relative to her. | ||

| “Crossing the line” means shooting consecutive shots from opposite sides of the line. |

| In this example the camera has crossed the line. As you can see in the resulting shot, the view of the subject is reversed and she appears to be walking from left to right.When cut immediately after the preceding shot, the effect is quite confusing. Because of the sudden reversal of viewpoint and action, this is known as a reverse cut.

|

To prevent reverse cuts, set up the scene so you can shoot it all from one side. If you are using multiple cameras, position them on the same side.

In some cases crossing the line is unavoidable, or at least desirable enough to be worth the awkward transition. In this case you can minimize confusion by using a shot taken on the line itself to go between the shots, as illustrated below. This “buffer” shot guides the viewer to the new position so they know where they are. Although it’s still not perfect, it’s not such a severe jolt.

Sports & Multi-Camera Action

In live-action situations such as sports coverage, crossing the line is often necessary to obtain the best views. Sometimes this isn’t a problem, especially if it’s a view the audience is used to, but sometimes it can be very confusing (for example, a team suddenly seems to be playing in the wrong direction). This can be alleviated by either a graphic key saying something like “Reverse Angle”, or a word from the commentator such as “Let’s see that replay from a different angle”.

The 180° Rule

The rule of line-crossing is sometimes called the 180° rule. This refers to keeping the camera position within a field of 180°.

The Rule of Thirds

The rule of thirds is a concept in video and film production in which the frame is divided into into nine imaginary sections, as illustrated on the right. This creates reference points which act as guides for framing the image.

Points (or lines) of interest should occur at 1/3 or 2/3 of the way up (or across) the frame, rather than in the centre. Like many rules of framing, this is not always necessary (or desirable) but it is one of those rules you should understand well before you break it.

In most “people shots”, the main line of interest is the line going through the eyes. In this shot, the eyes are placed approximately 1/3 of the way down the frame.

Depending on the type of shot, it’s not always possible to place the eyes like this.

In this shot, the building takes up approximately 1/3 of the frame and the sky takes up the rest. This could be a “weather shot”, in which the subject is actually the sky.

Traditional Film Camera Techniques

In film and video production the cinematographer sets the camera shots and decides what camera movement is necessary for a scene. An excellent way to learn how to be a cinematographer is to take filmmaking courses, since the methods of film cinematography are valid for computer animation.

One potential problem in computer animation is that animators try too much razzle dazzle with the camera – if the viewer notices the camera action too much then they won’t really notice the animation. Since most viewers have already seen countless hours of film or video, if you use the camera in traditional methods then it adds rather than detracts from the experience.

The following are the camera elements in any scene:

- Field of View

- Transitions

- Camera Angle

- Camera moves

- Panning

- Dolly shot

- Crane shot

- Lenses

- Zoom Lenses and the Vertigo Effect

- Depth of Field Effects

Field of View

| The Field of View (FOV) is the angle described by a cone with the vertex at the camera’s position. It is determined by the camera’s focal length, with the shorter the focal length the wider the FOV. For example, for a 35mm lens the FOV is 63 degrees (wide-angle), for a 50 mm lens it is 46 degrees (normal), and for a 135 mm lens it is 18 degrees (telephoto). A wide angle lens exaggerates depth while a telephoto lens minimizes depth differences. |

Standard camera shots using different length lenses

Shot | Visual Composition | Use |

| Extreme long shot | characters are small in frame; all or major parts of buildings appear | establishes physical context of action; shows landscape and architectural exteriors |

| Long shot | All or nearly all of the standing person; large parts of a building | shows a large scale action; shows whole groups of people; displays large architectural details |

| Medium shot | Character shown from waist up; medium-sized architectural details | small groups such as two or three people |

| Close-up | Head and neck of character; objects about the size of the desktop computer fill frame | focus on one character; facial expression very important |

| Extreme close-up | The frame filled with just part of a character or very small objects | facial features in a character or small objects |

Transitions

In film or video scene consists of a sequence of shots. Each shot is made from a different perspective and then they are joined together. The joining together of the individual shots to make a particular scene is accomplished through transitions.

The transition may be from one camera angle to another camera angle or from one camera to another camera. When you do transitions as a CG animator you are fulfilling the role of the editor, whose task is to put together a set of individual shots into a scene. One technique that film editors use is to focus on a particular element that is consistent between shots. This can be a physical object or it can be a compositional element such as a motion, color, or direction.

The simplest transition between shots it is a straight cut, which is an abrupt transition between two shots. Another type of transition is called a fade, in which the overall value of the scene increases or decreases into a frame of just one color. For example, a fade to black may indicate the end of the sequence. When one scene fades out as another scene fades in this is a dissolve. These dissolves are used frequently to indicate a passage of time. For example, you might have a shot moving down a hall and then a dissolve as it moves into a different part of the building.

Another type of transition is when one scene wipes across the frame and replaces the previous seen. Wipes can move in any direction and open one side to the other or they can start in the center and move out or the edge of the frame and move in. Wipes are very noticeable and best not used often.

Camera Angle

The camera angle helps to determine the point of view of the camera. This is very important since viewers have seen much TV or film and this has conditioned them to interpret the cameras “eye level” as containing meaning. Viewers expect the camera to show a level horizon. If the camera is not then it appears sinister to them. The cameras height above ground level and its angle in relationship to the ground should reflect real-life. A birds eye or worms eye view is unnatural and draws attention to itself. This may be all right if there’s a reason. However, it may detract from the content of the animation. Something that is a problem in CG. is that the ease of moving or putting a virtual camera anywhere may lead to excessive use of inappropriate camera angles.

A good idea is to observe existing film and video and to determine how far above ground level the camera is for a particular scene and use that information. For example, in a wide-angle shot the camera is usually in position of a viewer sitting down. In close-ups males are usually shown from just below eye level and females from just above eye-level. Placing a camera at the eye level of a standing person actually appears too high most of the time.

Camera moves

There are several fundamental camera moves that were developed right after the invention of motion picture cameras and are still used today. Using a virtual camera you can make almost any move, however, it is still a good idea to use these real world moves. These moves include the following:

Panning and Tilting

For both of these shots the camera is stationary and rotates in a horizontal (panning) or vertical (tilting) plane.

Panning is used to follow a moving object or character, or to show more than can fit into a single frame, such as panning across a landscape. It is also used as a transition between one camera position and another.

Inexperienced operators may pan too fast and caused an effect known as strobing. This is also a problem in CG and is called tearing. This can cause motion sickness or cause the illusion of motion to be broken. For example, for an animation at 30 fps, the number of frames needed for a 45 degree pan would be about 22 frames for a quick turn or 66 frames for a casual turn.

One way to avoid strobing is to use scene motion blur when rendering. This blur is done by sharing information between frames. Note that this is a scene motion blur where a scene shares information from the prior and next scenes. This is not the same as object motion blur.

The same motion considerations about panning are valid for tilting.

Dolly and Tracking shots

A dolly is a small wheeled vehicle, piloted by a dolly grip, that is used to move a camera around in a scene. A dolly shot is a move in and out of a scene, i.e., the movement is parallel to the camera lens axis. A tracking shot is a movement perpendicular to the camera lens axis. The key to these shots is to have realistic motion. The motion can be judged by looking at how fast humans move and then how many frames it would take to realize this motion. Examples of motion at different speeds are given in the table below.

| Miles per hour | Feet per second | Number of Frames to move 10 feet at 30 fps | |

| Casual stroll | 2 | 2.9 | 102 |

| Average walk | 3 | 4.4 | 68 |

| Brisk walk | 4 | 5.9 | 51 |

| Average jog | 6 | 8.8 | 34 |

| Average run | 8 | 11.7 | 26 |

| All out sprint | 12 | 17.6 | 17 |

| Car | 30 | 44 | 7 |

It is also important to have realistically smooth starts and stops in your shots.

Crane or Boom shot

This is when the camera moves up or down, as if it were on a physical crane. The same considerations for panning and tilting apply for crane shots.

Zoom Lenses and the Vertigo Effect

A Zoom lens has a variable focal length and so camera “moves” can be made without actually moving the camera. Professional cinematographers use the zoom very sparingly and generally prefer to move the camera. Amateurs love the zoom and can create some very nauseating motion by combining zooms and rapid pans. A zoom changes the angle of display so spatial relationships also change.

In the movie “Vertigo”, Alfred Hitchcock took advantage of this feature to create a what is now known as the vertigo shot. This involves synchronizing the movement of the subject with the zoom so that the subject is always the same size, but the background changes.

Depth of Field Effects

Real cameras have a depth of field, i.e., only part of the image is in focus at anyone time. The depth of field is a function of the lens length with short lenses (wide-angle) having a large depth of field and telephoto lenses have a small depth of field. Many CG cameras have an infinite depth of field, i.e., everything is in focus, and this looks unnatural. More advanced CG systems have cameras that emulate real lenses this way.

One way to change the center of attention in a scene is to have one object, e.g., in the foreground, in focus, with the background out of focus. Then an object in the background is brought into focus, with the foreground object now out of focus. For example, two people might be having a conversation in a crowded room and only they are in focus. Then the focus changes to reveal a person several feet away looking intensely at the two people. Here is an example prepared in 3D Studio Max 2.

| In this first scene, the creature and Debbie are having an innocent conversation, with the center of focus and attention on them. | |

| Next we switch to focusing on the evil alien as he covertly observes their conversation. |

Video Camera Filters

Camera filters are transparent or translucent optical elements which are either attached to the front of the lens or included as part of the lens housing. Filters alter the properties of light before it reaches the CCD.

Filters can be used to correct problems with light or to create certain effects.

Common types of filter include:

| Neutral Density (ND) | A colour-neutral filter which absorbs light evenly throughout the visible spectrum. Used to reduce the amount of light coming through the lens in strong lighting situations. |

| Ultra Violet (UV) | Video cameras are sensitive to both visible light and ultra violet (UV) light. UV is invisible to humans but it can create a blue tinge and/or washed-out effect on video, especially outside. A UV filter removes UV light while leaving visible light intact. UV filters are also commonly used as a protective filter for the lens. |

| Polarizing | A special type of lens which removes polarized light, reducing the washed-out effect sometimes created by reflected light. This results in more saturated, vibrant colours. Polarized filters are usually mounted with a rotational adjustment to align the polarization. |

| Diffusion | Effectively blurs the image for a slightly soft look. A mild diffusion filter can be used to soften faces (remove wrinkles etc), a stronger filter can be used to create a dream-sequence effect. |

| Sepia | Creates a sepia-tone effect, commonly used to depict historical images or flashbacks. |

| Fog | Creates a fog effect. |

| Colour Conversion / Correction | Adjusts the colour temperature of the light. |

| Star Effect | Makes single points of light stretch out in various star patterns. This effect is created by numerous fine etches in the filter, and can be used to give a dramatic, sophisticated or glamorous look to the image. |

cc

Graduated Filters are graduated from one part of the filter to another, for example, a graduated ND filter might have a strong ND filter on one half and none on the other half. This could be used to frame an image which is half sky, if you only want the sky to be affected by the filter.

Graduated filters have varying levels of transition. A sharp transition means there is a well-defined line between different parts of the filter. With soft transitions, the graduation is smoother.

Timecode Displays for Video

The video clips below are frame-accurate video timecode displays which can be downloaded and used with your video project to provide a timecode reference. The timecode clips are 160×40 pixels and can be placed anywhere in your video frame, as per the example on the right.

Notes:

- Choose the correct format to suit your project from the list below.

- These are big files — you might want to download the 1-minute version first to make sure it works.

- Windows video files use the Microsoft Video 1 codec.

- Quicktime files use the H.264 codec.

- MPEG2 files have the extension .m2v. If your editor doesn’t recognise it, try changing the extension to .mpg.

- If the timecode looks squashed or stretched in your project, try changing the pixel aspect ratio of the timecode clip. You can also resize it if you wish.

Lighting Technique

Reflector Board

Sometimes referred to as a “flecky board”, this is a specially-designed reflective surface which is usually used to act as a secondary light source. It is particularly useful as a fill light when working in strong sunlight.

Reflector boards come in white, silver or gold surfaces. Many reflectors have a different type of surface on each side, giving you two lighting options. Gold surfaces provide a warmer look than silver or white.

If you don’t have a reflector board you can improvise. Almost any suitably-sized object with a reflective surface will do. Some examples include:

- Windscreen sunshades for automobiles

- Polystyrene sheets

- Tin foil on cardboard (try both sides of the foil for different effects)

- Whiteboard

How to Fold Up a Reflector Board

Reflector boards are lightweight and flexible, and are normally folded up for transport in a small carry-case. They can be tricky to fold up — if you’ve never done it you may want to read the instructions below and practice in private before having to do it in front of the whole crew!

| Hold the board with your left hand facing forward and your right facing backward. Move your left hand forward and down, while moving your right hand backwards and up. | Keep moving your hands in a smooth motion. | The board will end up folded in a compact circle. You can then return the board to its case. |

The Standard 3-Point Lighting Technique

The Three Point Lighting Technique is a standard method used in visual media such as video, film, still photography and computer-generated imagery. It is a simple but versatile system which forms the basis of most lighting. Once you understand three point lighting you are well on the way to understanding all lighting.

The technique uses three lights called the key light, fill light and back light. Naturally you will need three lights to utilise the technique fully, but the principles are still important even if you only use one or two lights. As a rule:

- If you only have one light, it becomes the key.

- If you have 2 lights, one is the key and the other is either the fill or the backlight.

Key LightThis is the main light. It is usually the strongest and has the most influence on the look of the scene. It is placed to one side of the camera/subject so that this side is well lit and the other side has some shadow. | |

Fill LightThis is the secondary light and is placed on the opposite side of the key light. It is used to fill the shadows created by the key. The fill will usually be softer and less bright than the key. To acheive this, you could move the light further away or use some spun. You might also want to set the fill light to more of a flood than the key. | |

Back LightThe back light is placed behind the subject and lights it from the rear. Rather than providing direct lighting (like the key and fill), its purpose is to provide definition and subtle highlights around the subject’s outlines. This helps separate the subject from the background and provide a three-dimensional look. |

Lighting with Background Windows

Shooting pictures indoors with external windows is a common issue for photographers and video makers. The large difference in light levels between the room and the outside view make finding the correct exposure a challenge. Video is particularly susceptible to this problem due to it’s relatively low contrast ratio.

If you can’t avoid having the window in shot, in most cases the only thing you can do is use the manual iris to set your exposure correctly for the subjects in the room. This means that the window will be over-exposed but that’s a necessary compromise. If you wish to show the outside view, expose the iris for the window (which will make the room dark).

If you have time and resources available, there are two things you can do to help even out the lighting so it’s possible to capture both areas effectively:

- Add more light to the room

- Reduce the light from the window

(1) Increase the Lighting in the Room

Any extra light you can shine on the subject will decrease the contrast ratio between them and the window.

In some cases switching on the standard room lighting can help, although this often introduces new problems such as clashing colour temperatures and harsh downward shadows.

It’s possible that a reflector board could be useful.

(2) Reduce the Light from the Window

You can reduce the amount of light coming through the window by placing some sort of filter over it.

In the example pictured here, black scrim (a fine mesh material) is taped to the window. You can see that the background is much more manageable through the scrim.

If the entire window needs to be in shot you’ll need to be careful and discreet with the scrim/filter. It can be difficult getting exactly the right fit. If only part of the window is in shot it’s a lot easier.

Filters can cause unwanted side effects such as ripple and the moire effect. Being further away from the window helps.

Lighting Effects

Cold / Warm

You can add to the feeling of coldness or warmth by using additional filters or doubling up on gels. Very blue means very cold, very red/orange means very hot.

Moonlight (or any night-time light)

This is an old standard technique which has become something of a cliché. You can make daytime seem like night by lowering the exposure slightly and adding a blue filter to the camera. However a convincing illusion may require more effort than this — you don’t want any daytime giveaways such as birds flying through shot. You also need to think about any other lighting which should appear in shot, such as house or street lights.

Firelight

To light a person’s face as if they were looking at a fire, try this: Point a redhead with orange gel away from the subject at a large reflector which reflects the light back at the subject. Shake the reflector to simulate firelight (remember to add sound effects as well).

Watching TV

To light a person’s face as if they were watching TV, shine a blue light at the subject and wave a piece of cloth or paper in front of the light to simulate flickering.

Lighting For Video & Television

Video lighting is based on the same principles as lighting for any other visual media. If you haven’t done so already, you should read through our general lighting tutorials before reading this page, which deals specifically with lighting issues for video.

Light Sources

All video uses some sort of lighting, whether it be natural light (from the sun) or artificial lights. The goal of video lighting is to choose the best source(s) to achieve your goals.

First and foremost you need enough light. You must ensure that your camera is able to record an acceptable picture in the conditions. With modern cameras this is seldom a problem except in very low light or strong contrast.

Assuming you have enough light, you must then consider the quality of the light and how the various light sources combine to produce the image.

If you have clashing light sources (e.g. artificial interior lights with sunlight coming through the windows), you may find the colours in your image appear unnatural. It’s best to control the light sources yourself if possible (e.g. turn off the lights or close the curtains).

When moving between locations, think about what light source you are using. If you move from an outside setting to an inside one with artificial lights, the amount of light may seem the same but the colour temperature will change according to the type of lights. In this case you need to white balance your camera for the new light source.

Contrast Ratio

Contrast ratio is the difference in brightness between the brightest and darkest parts of the picture. Video does not cope with extreme contrast as well as film, and nowhere near as well as the human eye. The result of over-contrast is that some parts of the picture will be too bright or too dark to see any detail. For this reason you need to ensure that there is not too much contrast in your shot.

Camera-Mounted Lights

The camera-mounted light is an easy, versatile solution used by amateurs and professionals alike. Typically the light will draw power from the camera battery, although a separate power supply can be used. Be aware that lights which draw power from the camera battery will significantly shorten the battery’s charge time.

This type of lighting does not create pleasing effects. it is a “blunt instrument” approach which is really only designed to illuminate the scene enough to allow normal camera operations. However it is a simple, practical solution.

Night-Mode Video Shooting

Some cameras offer a special “night vision” option which allows you to shoot with virtually no light. This mode uses infrared light instead of normal visible light.

This is useful in extreme circumstances when you have no other option. Unfortunately the results tend to be poor-quality monochrome green.

Of course, you can use this mode for a special effect if it suits the content.

Common Lighting Terminology

| Ambient Light | The light already present in a scene, before any additional lighting is added. |

| Incident Light | Light seen directly from a light source (lamp, sun, etc). |

| Reflected Light | Light seen after having bounced off a surface. |

| Colour | A standard of measuring the characteristics of light, measured in kelvins. |

| Contrast Ratio | The difference in brightness between the brightest white and the darkest black within an image. |

| Key Light | The main light on the subject, providing most of the illumination and contrast. |