Biography of Simone de Beauvoir

Simone de Beauvoir – French writer, intellectual, existentialist philosopher, political activist, feminist and social theorist.

Name: Simone Lucie Ernestine Marie Bertrand de Beauvoir

Date of Birth: 9 January 1908

Place of Birth: Paris, France

Date of Death: 14 April 1986 (aged 78)

Place of Death: Paris, France

Occupation: Writer

Father: Georges Bertrand De Beauvoir

Mother: Françoise Brasseur

Children: Sylvie Le Bon-de Beauvoir

Early Life

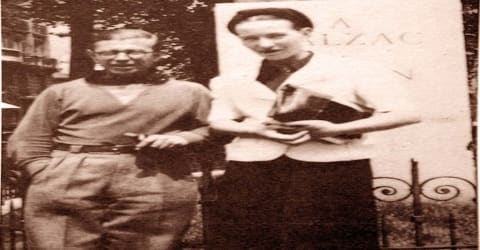

Simone de Beauvoir, French writer, and feminist, a member of the intellectual fellowship of philosopher-writers who have given a literary transcription to the themes of Existentialism, was born on 9 January 1908 into a bourgeois Parisian family in the 6th arrondissement. Though she did not consider herself a philosopher, she had a significant influence on both feminist existentialism and feminist theory. She is known primarily for her treatise Le Deuxième Sexe, 2 vol. (1949; The Second Sex), a scholarly and passionate plea for the abolition of what she called the myth of the “eternal feminine.” This seminal work became a classic of feminist literature. De Beauvoir also lent her voice to various political causes and traveled the world extensively.

Her diverse corpus includes novels, short stories, travel diaries, essays, philosophy, ethical writings, biographies, autobiographies, social issues, and politics. She had a major influence on feminism, feminist theory and feminist existentialism which is prominent from her revolutionary masterpiece ‘The Second Sex’ that deals with the oppression of women. Her other notable writings include ‘She Came to Stay’, ‘The Ethics of Ambiguity’, ‘The Mandarins’ and ‘Pyrrhus et Cineas’. Many of her writings speak strongly of her philosophical bent of mind which was influenced by idealisms and philosophy of Friedrich Engels, Karl Marx, Martin Heidegger and Descartes among others.

She had an open relationship with famous philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre. Although most of her ideas were original and sometimes different from Sartre, many times Simone de Beauvoir was unfairly tagged as a follower of Sartrean philosophy. Throughout her life, she remained under close scrutiny of the public.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Simone de Beauvoir, in full Simone Lucie-Ernestine-Marie-Bertrand de Beauvoir (French: simɔn də bovwaʁ), was born in Paris to Georges Bertrand de Beauvoir and Françoise Beauvoir on January 9, 1908. Her parents were Georges Bertrand de Beauvoir, a legal secretary who once aspired to be an actor, and Françoise de Beauvoir (née Brasseur), a wealthy banker’s daughter and devout Catholic. Simone’s sister, Hélène, was born two years later.

Simone was educated at a strict Catholic school for girls. After World War I (1914–18), her father suffered money problems, and the family moved to a smaller home. Beauvoir entered the Sorbonne and began to take courses in philosophy (the search for an understanding of the world and man’s place in it) to become a teacher. By this time she no longer believed all, she had been taught in Catholic school. She also began keeping a journal which became a lifetime habit and writing some stories.

After passing baccalaureate exams in mathematics and philosophy in 1925, she studied mathematics at the Institut Catholique de Paris and literature/languages at the Institut Sainte-Marie. She then studied philosophy at the Sorbonne and after completing her degree in 1928, she wrote her diplôme d’études supérieures (roughly equivalent to an MA thesis) on Leibniz for Léon Brunschvicg (the topic was “Le concept chez Leibniz” (“The Concept in Leibniz”)). De Beauvoir was only the ninth woman to have received a degree from the Sorbonne at the time, due to the fact that French women had only recently been allowed to join higher education.

She stood second in the philosophy aggregation test writing a thesis on Leibniz thus becoming the youngest ever to pass the exam and later became the youngest teacher of Philosophy in France. It is here that she met fellow student Jean-Paul Sartre who stood first in the exam.

Writing of her youth in Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter she said: “…my father’s individualism and pagan ethical standards were in complete contrast to the rigidly moral conventionalism of my mother’s teaching. This disequilibrium, which made my life a kind of endless disputation, is the main reason why I became an intellectual.”

Personal Life

Simone never married but remained in a life-long relationship with famous philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre since October 1929. Perhaps her most famous lover was American author Nelson Algren whom she met in Chicago in 1947, and to whom she wrote across the Atlantic as “my beloved husband.” Algren vociferously objected to their intimacy becoming public. Years after they separated, she was buried wearing his gift of a silver ring. However, she lived with Claude Lanzmann from 1952 to 1959.

De Beauvoir was bisexual and her relationships with young women were controversial. Former student Bianca Lamblin (originally Bianca Bienenfeld) wrote in her book Mémoires d’une jeune fille dérangée (English: Memoirs of a Disturbed Young Lady), that, while she was a student at Lycée Molière, she had been sexually exploited by her teacher de Beauvoir, who was in her 30s at the time. In 1943, de Beauvoir was suspended from her teaching job, due to an accusation that she had seduced her 17-year-old lycée pupil Natalie Sorokine in 1939. Sorokine’s parents laid formal charges against de Beauvoir for debauching a minor and as a result, she had her license to teach in France permanently revoked.

Simone adopted Sylvie Le Bon as her daughter who was her literary heir. In 1977, de Beauvoir, Sartre, Roland Barthes, Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida and much of the era’s intelligentsia signed a petition seeking to abrogate the age of consent in France.

Career and Works

Simone de Beauvoir started her career as a teacher in 1931 in a lycée at Marseilles. In 1932 she moved to Rouen to teach advanced literature and philosophy in the ‘Lycée Jeanne d’Arc’. As she advocated pacifism and was outspoken about the condition of women, she was officially admonished. Later in 1941, the Nazi Government discharged her from her post of teacher.

From 1929 to 1943, de Beauvoir taught at the lycée level until she could support herself solely on the earnings of her writings. She taught at the Lycée Montgrand (Marseille), the Lycée Jeanne-d’Arc (Rouen), the Lycée Molière (Paris) (1936–39). During October 1929, Jean-Paul Sartre and de Beauvoir became a couple, they entered a lifelong relationship. Sartre and de Beauvoir always read each other’s work. Debate continues about the extent to which they influenced each other in their existentialist works, such as Sartre’s Being and Nothingness and de Beauvoir’s She Came to Stay and “Phenomenology and Intent”. However, recent studies of de Beauvoir’s work focus on influences other than Sartre, including Hegel and Leibniz. The Neo-Hegelian revival led by Alexandre Kojève and Jean Hyppolite in the 1930s inspired a whole generation of French thinkers, including Beauvoir and Sartre, to discover Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit.

The first installment of Beauvoir’s autobiography (the story of her life), Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter, describes her rejection of her parents’ middle-class lives. The second volume, The Prime of Life, covers the years 1929 through 1944, a time when she and Sartre were both teachings in Paris and she was, she said, too happy to write. That happiness ended with the beginning of World War II (1939–45) and problems in her relationship with Sartre, who became involved with another woman and was also imprisoned for more than a year. During this unhappy time Beauvoir composed her first major novel, She Came to Stay (1943), a study of the effects of love and jealousy. In the next four years, she published The Blood of Others, Pyrrhus et Cinéas, Les Bouches Inutiles, and All Men are Mortal. America Day By Day, a chronicle of Beauvoir’s 1947 trip to the United States, and the third part of her autobiography, Force of Circumstances, cover the period during which the author was writing The Second Sex.

De Beauvoir’s first major published work was the 1943 novel She Came to Stay, which used the real-life love triangle between De Beauvoir, Sartre and a student named Olga Kosakiewicz to examine existential ideals, specifically the complexity of relationships and the issue of a person’s conscience as related to “the other.” She followed up the next year with the philosophical essay Pyrrhus and Cineas, before returning to fiction with the novels The Blood of Others (1945) and All Men Are Mortal (1946), both of which were centered on her ongoing investigation of existence.

In 1944 de Beauvoir wrote her first philosophical essay, Pyrrhus et Cinéas, a discussion of existentialist ethics. She continued her exploration of existentialism through her second essay The Ethics of Ambiguity (1947); it is perhaps the most accessible entry into French existentialism. In the essay, de Beauvoir clears up some inconsistencies that many, Sartre included, have found in major existentialist works such as Being and Nothingness. In The Ethics of Ambiguity, de Beauvoir confronts the existentialist dilemma of absolute freedom vs. the constraints of circumstance.

During the 1940s, De Beauvoir also wrote the play Who Shall Die? as well as editing and contributing essays to the journal Les Temps Modernes, which she founded with Sartre to serve as the mouthpiece for their ideologies. It was in this monthly review that portions of De Beauvoir’s best-known work, The Second Sex, first came to print.

In 1945 her political commitments and leftist orientation led her to associate with Jean-Paul Sartre, Raymond Aron, Maurice Merleau-Ponty among other intellectuals who founded a leftist journal, ‘Les Temps Modernes’. She continued to be an editor of the journal till her death. ‘Moral Idealism and Political Realism’, ‘Eye for an Eye’ and ‘Existentialism and Popular Wisdom’ are some of the remarkable articles worth mentioning.

Her novels expound the major Existential themes, demonstrating her conception of the writer’s commitment to the times. L’Invitée (1943; She Came To Stay) describes the subtle destruction of a couple’s relationship brought about by a young girl’s prolonged stay in their home; it also treats the difficult problem of the relationship of conscience to “the other,” each individual conscience being fundamentally a predator to another. Of her other works of fiction, perhaps the best known is Les Mandarins (1954; The Mandarins), for which she won the Prix Goncourt. It is a chronicle of the attempts of post-World War II intellectuals to leave their “mandarin” (educated elite) status and engage in political activism. She also wrote four books of philosophy, including Pour une Morale de l’ambiguité (1947; The Ethics of Ambiguity); travel books on China (La Longue Marche: essai sur la Chine (1957); The Long March) and the United States (L’Amérique au jour de jour (1948); America Day by Day); and a number of essays, some of them book-length, the best known of which is The Second Sex.

Written in 1949, The Second Sex had two main ideas: that man, who views himself as the essential being, has made a woman into the inessential being, “the Other,” and that femininity as a trait is an artificial posture. Sartre influenced both of these ideas. The Second Sex was perhaps the most important writing on women’s rights through the 1980s. When it first appeared, however, it was not very popular. The Second Sex does not offer any real solutions to the problems of women except the hope “that men and women rise above their natural differentiation (differences) and unequivocally (firmly) affirm their brotherhood.” The description of Beauvoir’s own life revealed the possibilities available to the woman who found ways to escape her situation. Hers was a life of equality, and she remained a voice and a model for those women not living free lives.

Four years later, the first English-language edition of The Second Sex was published in America, but it is generally considered to be a shadow of the original. In 2009, a far-more-faithful, unedited English volume was published, bolstering De Beauvoir’s already significant reputation as one of the great thinkers of the modern feminist movement.

Her travel diaries include ‘America Day by Day’ published in 1948 following her lecture in the US in 1947 and ‘The Long March’ in 1957 after she visited China with Sartre in 1955. During the 1950s and 1960s she wrote numerous essays, fictions, and short stories. Her book ‘Mandarins’ was published in 1954. It is about the personal lives of friends and philosophers belonging to and Sartre and her circle. She had dedicated the book to American writer Nelson Algren. The book also contained experiences of her relationship with Algren including sexual encounters. This book won her France’s highest literary prize, the Prix Goncourt.

Although The Second Sex established De Beauvoir as one of the most important feminist icons of her era, at times the book has also eclipsed a varied career that included many other works of fiction, travel writing, and autobiography, as well as meaningful contributions to philosophy and political activism.

In the chapter “Woman: Myth and Reality” of The Second Sex, de Beauvoir argued that men had made women the “Other” in society by application of a false aura of “mystery” around them. She argued that men used this as an excuse not to understand women or their problems and not to help them and that this stereotyping was always done in societies by the group higher in the hierarchy to the group lower in the hierarchy. She wrote that a similar kind of oppression by hierarchy also happened in other categories of identity, such as race, class, and religion, but she claimed that it was nowhere more true than with gender in which men stereotyped women and used it as an excuse to organize society into patriarchy.

In 2018 the manuscript pages of Le Deuxième Sexe were published. At the time her adopted daughter, Sylvie Le Bon-de Beauvoir, a philosophy professor, described her mother’s writing process: Beauvoir wrote every page of her books longhand first and only after that would hire typists.

In addition to treating feminist issues, de Beauvoir was concerned with the issue of aging, which she addressed in Une Mort très douce (1964; A Very Easy Death), on her mother’s death in a hospital, and in La Vieillesse (1970; Old Age), a bitter reflection on society’s indifference to the elderly. In 1981 she wrote La Cérémonie des adieux (Adieux: A Farewell to Sartre), a painful account of Sartre’s last years. Simone de Beauvoir: A Biography, by Deirdre Bair, appeared in 1990. Carole Seymour-Jones’s A Dangerous Liaison (2008), a double biography of de Beauvoir and Sartre, explores the unorthodox long-term relationship between the two.

The fourth installment of her autobiography, All Said And Done, was written when Beauvoir was sixty-three. In it she describes herself as a person who has always been secure in an imperfect world: “Since I was 21, I have never been lonely. The opportunities granted to me at the beginning helped me not only to lead a happy life but to be happy in the life I led. I have been aware of my shortcomings and my limits, but I have made the best of them. When I was tormented by what was happening in the world, it was the world I wanted to change, not my place in it.”

The 1970s saw her in an active role in Women’s Liberation Movement in France and in 1971 she signed the ‘Manifesto of the 343’. It contained names of renowned ladies who professed to have gone through an abortion, which was illegal in France then but later legalized in 1974. Her four-volume autobiography includes ‘Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter’; ‘The Prime of Life; ‘Force of Circumstance’, ‘After the War and Hard Times’ and ‘All Said and Done’.

In 1981 she wrote La Cérémonie Des Adieux (A Farewell to Sartre), a painful account of Sartre’s last years. In the opening of Adieux, de Beauvoir notes that it is the only major published work of hers which Sartre did not read before its publication. She contributed the piece “Feminism alive, well, and in constant danger” to the 1984 anthology Sisterhood Is Global: The International Women’s Movement Anthology, edited by Robin Morgan.

Awards and Honor

The Mandarins are also considered as one of her most successful books and fetched her highest literary award of France, the ‘Prix Goncourt’ in 1954.

Death and Legacy

Simone de Beauvoir died in Paris on April 14, 1986, at the age of 78, in a Paris hospital. She is buried next to Sartre at the Montparnasse Cemetery in Paris.

Several volumes of her work are devoted to autobiography. These include Mémoires d’une jeune fille rangée (1958; Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter), La Force de l’âge (1960; The Prime of Life), La Force des choses (1963; Force of Circumstance), and Tout Compte fait (1972; All Said and Done). This body of work, beyond its personal interest, constitutes a clear and telling portrait of French intellectual life from the 1930s to the 1970s.

In the later stages of her career, De Beauvoir devoted a good deal of her thinking to the investigation of aging and death. Her 1964 work A Very Easy Death details her mother’s passing, Old Age (1970) analyzes the significance and meaning of the elderly in society and Adieux: A Farewell to Sartre (1981), published a year after his death, recalls the last years of her partner’s life.

Simone de Beauvoir revealed herself as a woman of formidable courage and integrity, whose life supported her thesis: the basic options of an individual must be made on the premises of an equal vocation for man and woman founded on a common structure of their being, independent of their sexuality.

Information Source: