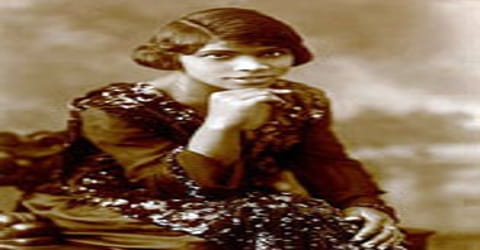

Biography of Marian Anderson

Marian Anderson – American singer.

Name: Marian Anderson

Date of Birth: February 27, 1897

Place of Birth: Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States

Date of Death: April 8, 1993 (aged 96)

Place of Death: Portland, Oregon, United States

Occupation: Singer

Father: John Berkley Anderson

Mother: Annie Delilah Rucker

Spouse/Ex: Orpheus H. Fisher (m. 1947 – died 1986)

Early Life

An African-American contralto, best remembered for her performance on Easter Sunday, 1939, on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington D.C. Marian Anderson was born on February 27, 1897, in Philadelphia, to John Berkley Anderson and the former Annie Delilah Rucker. Anderson was one of the most celebrated singers of the twentieth century. Music critic Alan Blyth said: “Her voice was a rich, vibrant contralto of intrinsic beauty.” Most of her singing career was spent performing in concert and recital in major music venues and with famous orchestras throughout the United States and Europe between 1925 and 1965. Her career was notable not only for her artistic achievements which were many but also for a dignified tenacity in the face of discrimination. She opened doors for subsequent generations of black American singers.

Anderson was born in Philadelphia and started displaying her extraordinary vocal talent from the time she was a child. However, her family was not well off and did not have enough means to pay for her formal vocal training. It was a magnanimous gesture shown by the members of Marian’s church congregation who raised funds, which enabled her to attend a music school for about a year. A major portion of her singing career was devoted to giving performances in recital in important music venues and in concerts as well as with well-known orchestras throughout Europe and the United States of America. Though she was offered various roles with many of the major European opera companies Marian declined all of them as she was not a trained actor. Her first preference had always to perform in recitals and concerts only. However, Marian did perform opera arias within her recitals and concerts. She did several recordings that were a reflection of her broad performance talents ranging from concert literature to traditional American songs, to opera and spirituals. Marian Anderson became one of the important personalities in the then ongoing struggle for many of the black artists for overcoming racial prejudices during the mid-twentieth-century in the United States of America.

Anderson worked for several years as a delegate to the United Nations Human Rights Committee and as a “goodwill ambassadress” for the United States Department of State, giving concerts all over the world. She participated in the civil rights movement in the 1960s, singing at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963. Anderson became a great advocate and role model for African-American musicians, never seeming to give up hope for the future of both her people and her country.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Marian Anderson was born on 27 February 1897, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the U.S. to John Berkley Anderson and Annie Delilah Rucker. Throughout her life, she gave her birth date as February 17, 1902, but her death certificate records her birth date as February 27, 1897, and there is a photograph taken of her as an infant that is dated 1898. She was the oldest of three daughters and was only 6 years old when she joined the choir as a member at a church called Union Baptist Church. She was given the nickname “Baby Contralto”.

Her father was a loader at the Reading Terminal Market, while her mother was a former teacher, having taught in Virginia. In 1912, her father suffered a head wound at work and died soon after. Marian and her two sisters, along with their mother moved in with her father’s parents. Her mother found work cleaning, laundering, and scrubbing floors. Anderson’s parents were both devout Christians and the whole family was active in the Union Baptist Church in South Philadelphia.

Anderson’s father bought her a piano when Marian was just 8-year-old. Since the family did not have enough means to send her for music lessons, the immensely talented Marian taught music herself. She lost her father when she was barely 12 years old and her mother had to raise the children single-handedly. However, this personal tragedy did not stop Marian from pursuing her musical ambitions. She was still deeply attached to her church as well as its choir where she rehearsed different parts such as bass, tenor, alto, soprano in the presence of her family till the time she perfected them.

Anderson attended Stanton Grammar School, graduating in the summer of 1912. Her family, however, could not afford to send her to high school, nor could they pay for any music lessons. She joined the Baptists’ Young People’s Union and the Camp Fire Girls which provided her with some limited musical opportunities. Eventually, the directors of the People’s Chorus and the pastor of her church, Reverend Wesley Parks, along with other leaders of the black community, raised the money she needed to get singing lessons with Mary Saunders Patterson and to attend South Philadelphia High School, from which she graduated in 1921. After high school, Anderson applied to an all-white music school, the Philadelphia Music Academy (now University of the Arts), but was turned away because she was black. Reflecting on that experience, Marian later stated:

“I don’t think I said a word. I just looked at this girl and was shocked that such words could come from one so young. If she had been old and sour-faced I might not have been startled. I cannot say why her youth shocked me as much as her words. On second thought, I could not conceive of a person surrounded as she was with the joy that is music without having some sense of its beauty and understanding rub off on her. I did not argue with her or ask to see her superior. It was as if a cold, horrifying hand had been laid on me. I turned and walked out.”

Her former high school principal enabled her to meet Guiseppe Boghetti, a much sought-after teacher. He was reportedly moved to tears during the audition when Marian performed “Deep River.”

Personal Life

Marian Anderson married Orpheus H. Fisher on 17 July 1943 at Bethel in Connecticut. Orpheus was an architect and Marian was her second wife. Her husband had initially proposed her when they were both teenagers. The wedding was a private ceremony performed by United Methodist pastor Rev. Jack Grenfell and was the subject of a short story titled “The ‘Inside’ Story” written by Rev. Grenfell’s wife, Dr. Clarine Coffin Grenfell, in her book Women My Husband Married, including Marian Anderson.

By this marriage, Marian had a stepson, James Fisher, from her husband’s previous marriage to Ida Gould. The couple had purchased a 100-acre (0.40 km2) farm in Danbury, Connecticut, three years earlier in 1940 after an exhaustive search throughout New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut. Through the years Fisher built many outbuildings on the property, including an acoustic rehearsal studio he designed for his wife. The property remained Anderson’s home for almost 50 years.

Orpheus H. Fisher, Marian’s husband died in 1986 after about 43 years of marriage. Anderson continued to live at Marianna Farm till the year 1992, just one year prior to her death.

Career and Works

Marian Anderson’s family could not afford high school education for her nor could they pay for her music lessons. However, her passion for singing helped her stay active in the musical activities in churches where she joined the adult choir. Her involvement with the Camp Fire Girls and Baptists’ Young People’s Union opened some musical opportunities.

In 1919, at the age of 22, Anderson sang at the National Baptist Convention. Gaining knowledge and confidence with each performance, on April 23, 1924, she dared her first recital at New York’s Town Hall. However, she was uncomfortable with foreign languages and critics found her voice lacking. This discouraging experience nearly caused her to end her vocal career. However, her confidence was soon bolstered when, while studying under Boghetti, she was granted the opportunity to sing at the Lewisohn Stadium in New York by entering a contest sponsored by the New York Philharmonic Society.

In 1925 Anderson got her first big break when she won first prize in a singing competition sponsored by the New York Philharmonic. As the winner, she got to perform in concert with the orchestra on August 26, 1925, a performance that scored immediate success with both audience and music critics. Anderson remained in New York to pursue further studies with Frank La Forge. During the time Arthur Judson, whom she had met through the New York Philharmonic, became her manager. Over the next several years, she made a number of concert appearances in the United States, but racial prejudice prevented her career from gaining much momentum. In 1928, she sang for the first time at Carnegie Hall. Eventually, she decided to go to Europe where she spent a number of months studying with Sara Charles-Cahier before launching a highly successful European singing tour.

A New York Times critic wrote: “A true mezzo-soprano, she encompassed both ranges with full power, expressive feeling, dynamic contrast, and utmost delicacy.” However, Ms. Anderson’s popularity was not catching on with mainstream America; she was still performing mainly for black audiences. The National Association of Negro Musicians awarded Marian a scholarship to study in Britain.

By the end of the 1930s, Anderson’s voice was famous on both sides of Atlantic. She was invited by the U.S. President Roosevelt and the First Lady Eleanor to give her performance at the White House. Marian Anderson was the first African American singer to receive this exceptional honor.

In 1933, Anderson made her European debut in a concert at Wigmore Hall in London, where she was received enthusiastically. She spent the early 1930s touring throughout Europe where she did not encounter the racial prejudices she had experienced in America. In the summer of 1930, she went to Scandinavia, where she met the Finnish pianist Kosti Vehanen who became her regular accompanist and her vocal coach for many years.

Anderson was intent on perfecting her language skills (as most operas were written in Italian and German) and learning the art of lieder singing. At a debut concert in Berlin, she attracted the attention of Rule Rasmussen and Helmer Enwall, managers who arranged a tour of Scandinavia. Enwall continued as her manager for other tours around Europe.

In 1934, impresario Sol Hurok offered Anderson a better contract than she previously had with Arthur Judson. He became her manager for the rest of her performing career and through his persuasion, she came back to perform in America. In 1935, Anderson made her second recital appearance at The Town Hall in New York City, which received highly favorable reviews by music critics. She spent the next four years touring throughout the United States and Europe. She was offered opera roles by several European houses but, due to her lack of acting experience, Anderson declined all of those offers. She did, however, record a number of opera arias in the studio, which became bestsellers.

In 1935, Anderson’s performance at the Salzburg festival earned her worldwide recognition and a compliment from the Italian conductor, Arturo Toscanini, who told her, “a voice like yours is heard only once in a hundred years.” The Finnish composer Jean Sibelius dedicated his Solitude to her. In 1935 impresario Sol Hurok took over as her manager and was with her for the remainder of her performing career.

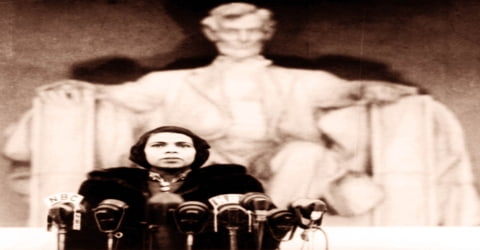

In 1939, Anderson scheduled an appearance at Constitution Hall in Washington, D.C., but was denied the use of the building by its owners, the Daughters of the American Revolution, who objected to the presentation of a black performer. Eleanor Roosevelt resigned her membership in the DAR in protest of this decision and then scheduled an appearance for Anderson at the Lincoln Memorial on Easter Sunday. The resulting concert, attended by thousands and broadcast nationwide, forever established Anderson as an ambassador for racial progress a role she embraced with great pride and success for the remainder of her career. Fittingly, Anderson’s 1955 appearance at the Metropolitan Opera marked the first by an African-American singer, preparing the way for such future stars as Leontyne Price and Shirley Verrett.

In 1943, Anderson sang at the invitation of the DAR to an integrated audience at Constitution Hall as part of a benefit for the American Red Cross. By contrast, the federal government continued to bar her from using the high school auditorium in the District of Columbia. On January 7, 1955, Anderson broke the color barrier by becoming the first African-American to perform with the New York Metropolitan Opera. On that occasion, she sang the part of Ulrica in Giuseppe Verdi’s Un Ballo in Maschera. The occasion was bittersweet as Anderson, at age 58, was no longer in her prime vocally.

In 1957, Anderson sang for President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s inauguration, toured India and the Far East as a goodwill ambassador through the U.S. State Department and the American National Theater and Academy. She traveled 35,000 miles (56,000 km) in 12 weeks, giving 24 concerts. After that, President Eisenhower appointed her as a delegate to the United Nations Human Rights Committee. The same year, she was elected Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. In 1958 she was officially designated delegate to the United Nations, a formalization of her role as “goodwill ambassadress” of the U.S. which she had played earlier.

On January 20, 1961, Marian Anderson sang for President John F. Kennedy’s inauguration, and in 1962 she performed for President Kennedy and other dignitaries in the East Room of the White House, and also toured Australia. She was active in supporting the civil rights movement during the 1960s, giving benefit concerts for the Congress of Racial Equality, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the America-Israel Cultural Foundation. In 1963, she sang at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. She also released her album, Snoopycat: The Adventures of Marian Anderson’s Cat Snoopy, which included short stories and songs about her beloved black cat.

Marian Anderson eventually retired from singing in 1965 after a long illustrious music career but she continued to make public appearances even after that. However, she continued to appear publicly, narrating Copland’s “A Lincoln Portrait,” including a performance with the Philadelphia Orchestra at Saratoga in 1976, conducted by the composer.

Awards and Honor

Marian Anderson worked for several years as a delegate to the United Nations Human Rights Committee and as a “goodwill ambassadress” for the United States Department of State and gave concerts throughout the world.

In 1955, Marian Anderson earned the distinction of becoming the first African American for performing at the New York Metropolitan Opera as a member.

Marian Anderson was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1963, the Congressional Gold Medal in 1977, the Kennedy Center Honors in 1978, the National Medal of Arts in 1986, and a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1991.

On January 27, 2005, a commemorative U.S. postage stamp honored Marian Anderson with her image on the 37¢ issue as part of the Black Heritage series. Anderson is also pictured on the $5,000 Series I United States Treasury Savings Bond.

Death and Legacy

Marian Anderson died of congestive heart failure on April 8, 1993, at age 96. She had suffered a stroke a month earlier. She died in Portland, Oregon, at the home of her nephew, conductor James DePreist, where she had relocated the year prior. She is interred at Eden Cemetery, in Collingdale, Pennsylvania, a suburb of Philadelphia.

Marian Anderson holds the record of being the first African-American to have sung at the Metropolitan Opera House in New York, both in the years 1955 and in 1956. She amazed the world by singing at the presidential inaugurations of John F. Kennedy and Dwight D. Eisenhower. In 1957, she made an extensive concert tour of the far east of the US State Department and India. Her European singing tour in the 1920s was the most popular of her times.

Marian Anderson’s voice was dark, rich, and possessed of great power and agility. Her repertory ranged from opera and concert material to Negro spirituals, and she brought to all things a great sense of commitment and integrity. Arturo Toscanini is noted to have remarked that a voice like hers only appears “once in a hundred years.” While her voice was most distinctive in the lower range, she was also capable of lightening it almost to leggiero proportions as she did in works of Handel and other Baroque composers and of bringing a near-ideal combination of classical training and folk-like spontaneity to the spirituals that were an integral part of her concert and recording repertoire.

The 1939 documentary film, Marian Anderson: the Lincoln Memorial Concert was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry.

Information Source: