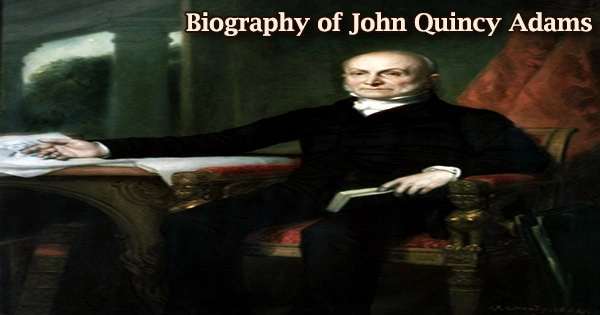

Full name: John Quincy Adams

Date of birth: July 11, 1767

Place of birth: Braintree, Massachusetts Bay, British America (now Quincy)

Date of death: February 23, 1848 (aged 80)

Place of death: Washington, D.C., U.S.

Occupation: Politician; Lawyer

Political party: Federalist (1792–1808); Democratic-Republican (1809–1828); National Republican (1828–1830); Anti-Masonic (1830–1834); Whig (1834–1848)

Father: John Adams

Mother: Abigail Smith

Spouse: Louisa Johnson (m. 1797)

Children: George, John II, Charles, Louisa

Early Life

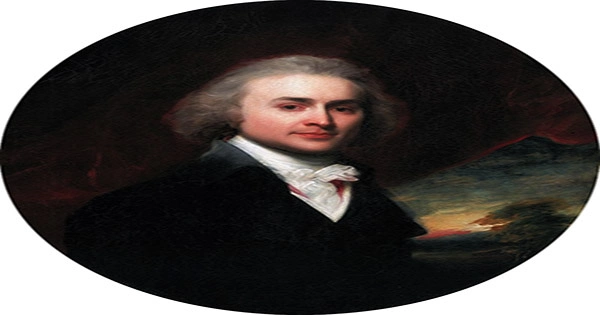

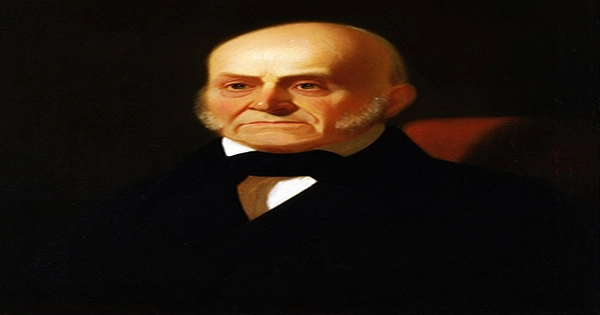

John Quincy Adams (/ˈkwɪnzi/; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848), often known as “Old Man Eloquent”, was the sixth President of the United States, serving from 1825 to 1829. He was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the eighth Secretary of State of the United States from 1817 until 1825. He was one of America’s best diplomats during his pre-presidential years (formulating, among other things, the Monroe Doctrine), and during his post-presidential years (as a U.S. congressional representative, 1831–48), he waged a constant and often spectacular campaign against the extension of slavery.

Adams holds the distinction of being the first President of the United States whose father had previously served in the position. Because he was the son of John Adams, the second President of the United States, patriotism ran in his veins. Adams’ disposition was that of a recluse, and he did not mingle much, despite his remarkable intellect. Adams also served as an ambassador and a member of the United States Senate and House of Representatives, representing Massachusetts, during his long diplomatic and political career.

These behavioral traits are thought to have lost him his presidential reelection effort, and as a result, his leadership was limited to a single term. He became a lawyer after graduating from Harvard College. He was appointed Minister to the Netherlands at the age of 26 and later promoted to the Berlin Legation. He was elected to the United States Senate in 1802. President Madison nominated him Minister to Russia six years later.

Adams was inducted into the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia in 1818. Although Adams’ career had been nearly entirely successful, his president (1825–29), during which the country developed, was in many ways a political failure due to the Jacksonians’ vehement resistance. The Democrats proved to be more adept political organizers than Adams and his National Republican allies, and in the 1828 presidential election, Jackson easily defeated Adams, making him only the second president to lose re-election (his father being the first).

Adams did not retire from public duty; instead, he was elected to the House of Representatives, where he served from 1831 to 1848. He is acknowledged today as one of the greatest American diplomats and Secretaries of State the country has ever had. He is remembered as an amazing moral leader who helped create America’s foreign policy and ushered in an era of economic progress while upholding the country’s nationalist republican beliefs.

Childhood and Educational Life

John Quincy Adams was born on July 11, 1767, to John Adams (second President of the United States) and Abigail Adams (née Smith) in a part of Braintree, Massachusetts that is now Quincy. He received his early schooling at a private academy on the suburbs of Paris before enrolling at Leiden University on January 10, 1781, when he matriculated.

Adams was well-prepared for public service as a child, having accompanied his father on many diplomatic missions. From 1781 until 1782, he worked as a private secretary and interpreter for Francis Dana, the United States’ Minister to Russia.

From Penn’s Hill, he witnessed the Battle of Bunker Hill and heard the cannons thunder across Boston’s Back Bay. After the war had robbed Braintree of its only schoolmaster, his patriot father, John Adams, a delegate to the Continental Congress at the time, and his patriot mother, Abigail Smith Adams, had a great molding impact on his education.

In 1787, Adams graduated in Bachelor of Arts from Harvard College and later in 1790, earned an A.M. from Harvard. Between 1787 and 1789, he completed his apprenticeship as an attorney with Theophilus Parsons in Newburyport, Massachusetts. In 1791, he was admitted to the bar and thereafter started his law practice in Boston.

Personal Life

John Quincy Adams was married in London in 1797, on the eve of his departure for Berlin, to Louisa Catherine Johnson (Louisa Adams), daughter of the United States consul Joshua Johnson, a Marylander by birth, and his wife, Katherine Nuth, an Englishwoman. They had three sons and a daughter; their daughter, Louisa, was born in 1811 but died in 1812. They named their first son George Washington Adams (1801–1829) after the first president.

Both George and their second son, John (1803–1834), had terrible childhoods and died young. George, who had a lengthy history of drunkenness, died in 1829 after falling overboard on a steamboat; it is unclear if he fell or jumped from the boat on purpose. In 1834, John died of an unknown disease while running his father’s unproductive flour and grist mill.

Adams’s youngest son, Charles Francis Adams Sr., was an important leader of the “Conscience Whigs”, a Northern, anti-slavery faction of the Whig Party. In the 1848 presidential election, Charles ran as the vice presidential candidate for the Free Soil Party, and later became a prominent member of the Republican Party.

At the age of 22, Adams was profoundly in love with Mary Frazier, but his mother forbade him from marrying her, claiming that he couldn’t support a wife. Finally, Adams saw that marrying a wealthy heiress like Louisa Johnson might allow him to continue a writing career, but her family had financial setbacks and filed for bankruptcy only a few weeks after the wedding.

Few men in American history have possessed the independence, civic spirit, and ability that Adams possessed. Nonetheless, he was hampered throughout his political career by a personal reserve, austerity, and chilly demeanor that prevented him from appealing to the people’s imaginations and sympathies. He had few close friends, and few men in American history have faced such animosity or been vilified with such venom by their political opponents during their lifetimes.

Working and Political Career

Adams’ early diplomatic career, away from his father’s shadow, began in 1794, when he was nominated by then-President George Washington as minister to the Netherlands. He was appointed minister plenipotentiary to Berlin in 1797, but he returned to America at his father’s request after losing his presidential run in 1800. While in Berlin, Adams negotiated an amity and commerce contract with Prussia in 1799.

After being summoned from Berlin by President Adams following Thomas Jefferson’s election to the presidency in 1800, the younger Adams arrived in Boston in 1801 and was elected to the Massachusetts Senate the following year. He was elected to the Massachusetts State Senate in April 1802, after winning the elections. Up until this point, John Quincy Adams was thought to be a member of the Federalist Party, but he despised the party’s general policies. As the son of his father, he was despised by supporters of Alexander Hamilton and reactionary factions, and he quickly found himself helpless as an unpopular member of an unpopular minority.

Adams was one of America’s great secretaries of state, arranging with England for a joint occupation of the Oregon territory, winning the cession of the Floridas from Spain, and developing the Monroe Doctrine with the President. After a year in the State Senate, the Massachusetts General Court elected Adams to represent the state in the United States Senate, a position he held from March 4, 1803 to March 4, 1808.

In 1807, as a Senator, he voted in favor of the Louisiana Purchase and the Embargo, which was a departure from the Federalist Party’s position. In December 1807, he strenuously pushed immediate action on President Jefferson’s proposal of an embargo to effectively halt all trade with other nations (in an attempt to secure British recognition of American rights). Adams was a professor of logic at Brown University and the Boylston Professor of Rhetoric and Oratory at Harvard University while in the Senate. Adams’s devotion to classical rhetoric shaped his response to public issues, and he would remain inspired by those rhetorical ideals long after the neo-classicalism and deferential politics of the founding generation were eclipsed by the commercial ethos and mass democracy of the Jacksonian Era.

His successor was elected on June 3, 1808, many months ahead of schedule for electing a senator for the next term, and Adams resigned five days later. He linked himself with the Republican party by attending the Republican congressional caucus in the same year, which nominated James Madison for president. Many of Adams’ eccentric opinions stemmed from his unwavering commitment to Ciceronian ideals of the citizen-orator “speaking properly” for the good of the polis. British philosopher David Hume’s classical republican ideal of civic eloquence also influenced him.

President James Madison designated him as the first-ever minister plenipotentiary to Russia in 1809. Adams resided in St. Petersburg for the next five years with his wife and youngest kid. From there, he reported about Napoleon’s ambitious European adventure and disastrous effort to capture Russia in 1812. His Lectures on Rhetoric and Oratory (1810) examines the fate of classical oratory, the need for liberty for it to thrive, and its significance as a unifying feature for a new nation of many cultures and ideas.

The “public spaces of passionate oratory” collapsed in favor of the private sphere in the United States in the second decade of the nineteenth century, much as civic eloquence failed to acquire appeal in Britain. When the United States waged war on the United Kingdom in 1812, Adams attempted to mediate a peace between the two countries through Russian intervention. The impasse between America and Great Britain persisted, so he was summoned to the United States in 1814 to negotiate the Treaty of Ghent, which he successfully completed. This ended the War of 1812.

Adams was still in St. Petersburg when the conflict between the United States and England broke out in 1812. The Russian government suggested in September that the tsar was willing to mediate between the two belligerents. Madison quickly accepted the proposal and dispatched Albert Gallatin and James Bayard to function as commissioners alongside Adams, but England refused to participate.

These individuals, along with Henry Clay and Jonathan Russell, began negotiations with English commissioners in August 1814, which culminated in the signing of the Treaty of Ghent on December 24 of that year. Adams was appointed as the United States’ representative to the United Kingdom in 1815, a position he maintained until 1817. Adams returned to the United States in August 1817 after spending several years in Europe and was appointed Secretary of State by President Monroe. This appointment was primarily due to his diplomatic experience but also due to the president’s desire to have a sectionally well-balanced cabinet in what came to be known as the Era of Good Feelings.

From 1817 until 1825, Adams served as Secretary of State during Monroe’s eight-year presidency. Many of his accomplishments as Secretary of State, like as the 1818 convention with the United Kingdom, the Transcontinental Treaty with Spain, and the Monroe Doctrine, were the result of unanticipated occurrences. As Secretary of State, Adams was instrumental in Florida’s acquisition. Since the purchase of Louisiana, successive administrations have attempted to incorporate at least a portion of Florida in the deal.

After months of negotiations, Adams was able to persuade the Spanish minister to agree to a treaty in which Spain would relinquish all claims to territory east of the Mississippi River, the United States would relinquish all claims to what is now Texas, and the United States would draw a boundary from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean for the first time. This Transcontinental Treaty was possibly the biggest diplomatic victory ever gained by a single man in American history.

Adams was the driving force behind the notion of expanding the country’s northern border westward from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific, which was regarded as a diplomatic coup. It was a triumphant “epocha” in U.S. continental expansion, to use his own words. However, before the Spanish government ratified the Transcontinental Treaty in 1819, Mexico (including Texas) had broken its ties with the mother country, and the US had taken Florida by force.

Adams was keen on establishing American sovereignty over the Oregon Country, partially because he believed that doing so would increase trade with Asia. The Adams–Onís Treaty was ratified in February 1821 after extensive discussions between Spain and the United States. Though Adams was proud of the deal, he was privately apprehensive about the possibility of slavery spreading into the newly acquired territory. By ratifying the Russo-American Treaty of 1824, which fixed Russian Alaska’s southern border at 54°40′ north, the Monroe administration would enhance US claims to Oregon.

In 1821, the authoritative Report on Weights and Measures presented before the Congress was another of his major accomplishments. Besides this, he was also one of the key members behind the development of 1823 Monroe Doctrine. His run for the presidency in 1824 did not culminate in a unanimous victory, he became a minority president and his term extended from March 4, 1825, to March 4, 1829.

Adams, as Secretary of State, was seen as the political heir to the presidency in the early nineteenth century political tradition. However, before the clamor for a popular option in 1824, the conventional means of choosing a President were giving way. As president, he aspired to improve the country’s infrastructure by establishing a road and canal system, but his minority status hampered his passionate efforts. Despite all of the challenges, he was able to reduce the national debt from $16 million to $5 million during his brief presidency, which ended in 1829 after he failed his reelection bid.

Upon becoming President, Adams appointed Clay as Secretary of State. Jackson and his enraged supporters accused Adams of making a “corrupt bargain,” and they launched a campaign to grab the presidency from him in 1828. Despite the fact that he knew he would face opposition in Congress, Adams announced a stunning national program in his first Annual Message. He recommended that the federal government connect the sections with a network of highways and canals, as well as develop and conserve the public domain with revenues raised from the sale of federal property.

Adams outlined a detailed and ambitious program in his annual statement to Congress in 1825. He advocated for significant investments in internal reforms, as well as the establishment of a national university, naval academy, and astronomical observatory. Adams also advocated for the United States to take the lead in the growth of the arts and sciences by establishing a national university, funding scientific expeditions, and constructing an observatory. His detractors said that such actions went beyond the bounds of the Constitution.

After his defeat, Adams returned to politics, contesting the 1830 elections and winning a seat in the United States House of Representatives. From 1831 to 1848, he was a member of Congress. During this time, he became a vocal opponent of slavery, as well as the Mexican war and annexation of Texas. He remained active in politics to the end of his life.

Retirement and Later Life

The 78-year-old former president suffered a stroke in mid-November 1846, leaving him largely incapacitated. He recovered completely and resumed his work in Congress after a few months of relaxation. When Adams entered the House chamber on February 13, 1847, everyone “stood up and applauded.”

Death and Legacy

In 1848, Adams collapsed on the floor of the House from a stroke and was carried to the Speaker’s Room, where two days later he died at the age of 80. He was buried as were his father, mother, and wife at First Parish Church in Quincy. His last words were “This is the last of Earth. I am content”. Among those present for his death was Abraham Lincoln, then a freshman representative from Illinois.

His original interment was temporary, in the public vault at the Congressional Cemetery in Washington, D.C. Later, he was interred in the family burial ground in Quincy, Massachusetts, across from the (Unitarian) United First Parish Church, called Hancock Cemetery. After Louisa’s death in 1852, his son had his parents re-interred in the expanded family crypt in the United First Parish Church across the street, next to John and Abigail. Both tombs are viewable by the public. Adams’s original tomb at Hancock Cemetery is still there and marked simply “J.Q. Adams”.

Adams’ vast personal journal, which spans 50 large volumes, is one of his most important legacies. He began writing when he was 11 years old and continued to do so until his death. He envisioned a grand plan for national reforms as the sixth President of the United States, in which he hoped to secure federal assistance for the advancement of the arts and sciences.

Awards and Honours

John Quincy Adams Birthplace is now part of Adams National Historical Park and open to the public. Adams House, one of twelve undergraduate residential Houses at Harvard University, is named for John Adams, John Quincy Adams, and other members of the Adams family associated with Harvard.

In the 1997 film Amistad, his character was played by Anthony Hopkins and once again in 2008, a mini-series based on his life was showcased by HBO. His personal journals were kept under lock and key until 1951. It was then, when the unedited copies were released for the general public by his great grandsons.

An Adams Memorial has been proposed in Washington, D.C., honoring Adams and his wife, son, father, mother, and other members of their family. Several locations in the United States have used Adams’s middle name of Quincy, including the town of Quincy, Illinois. Adams County, Illinois, and Adams County, Indiana are also named after Adams. Adams County, Iowa, and Adams County, Wisconsin, were each named for either John Adams or John Quincy Adams.