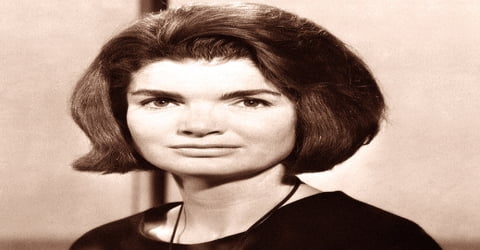

Biography of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis

Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis – American book editor and socialite who was First Lady of the United States.

Name: Jacqueline Lee Kennedy Onassis

Date of Birth: July 28, 1929

Place of Birth: Southampton, New York, United States

Date of Death: May 19, 1994 (aged 64)

Place of Death: New York City, New York, United States

Father: John Vernou Bouvier III

Mother: Janet Lee Bouvier

Spouse: John F. Kennedy (m. 1953; died 1963), Aristotle Onassis (m. 1968; died 1975)

Children: John F. Kennedy Jr., Caroline Kennedy, Patrick Bouvier Kennedy

Early Life

Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis (An internationally famous first lady), was born on July 28, 1929, in Southampton, New York, to Wall Street stockbroker John Vernou Bouvier III and his wife, Janet Lee Bouvier. In 1951, she graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in French literature from George Washington University and went on to work for the Washington Times-Herald as an inquiring photographer.

In 1952, Jacqueline met then-Congressman John F. Kennedy at a dinner party in Washington. She married John F. Kennedy in 1953. When she became the first lady in 1961, she worked to restore the White House to its original elegance and to protect its holdings. After JFK’s assassination in 1963, she moved to New York City. She married Aristotle Onassis in 1968.

Following her husband’s election to the presidency in 1960, Jacqueline Kennedy was known for her highly publicized restoration of the White House and emphasis on arts and culture, as well as for her style, elegance, and grace. Only 31 years old when her husband was inaugurated, she was the youngest First Lady since Frances Cleveland. She was also the first Catholic to serve as First Lady. On November 22, 1963, Jacqueline Kennedy was riding with the President in an open-air motorcade in Dallas, Texas, when he was assassinated. Following his funeral, she and her children largely withdrew from public view.

In 1968, Jacqueline married Greek shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis. Following Aristotle Onassis’s death in 1975, she had a career as a publishing editor in New York City. She died on May 19, 1994, of Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, aged 64.

During her lifetime, Jacqueline Kennedy was regarded as an international fashion icon. Her famous ensemble of a pink Chanel suit and matching pillbox hat has become a symbol of her husband’s assassination. Even after her death, she ranks as one of the most popular and recognizable First Ladies and was listed as one of Gallup’s Most-Admired Men and Women of the 20th century in 1999.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, née Jacqueline Lee Bouvier, later (1953–68) Jacqueline Kennedy, byname Jackie, was born on July 28, 1929, to Janet Lee Bouvier (1908–) and John (Jack) Vernon Bouvier III (1892–1957), at Stony Brook Southampton Hospital in Southampton, New York. Bouvier’s mother was of Irish descent, and her father had French, Scottish, and English ancestry. Named after her father, Bouvier was baptized at the Church of St. Ignatius Loyola in Manhattan; she was raised in the Catholic faith. Her sister Lee was born in 1933.

As a child, Jacqueline developed the interests she would still relish as an adult: horseback riding, writing, and painting. In 1942, after her parents had divorced and her mother married Hugh D. Auchincloss, Jr., a wealthy lawyer, Jacqueline divided her time between the family’s Merrywood estate in Virginia and Hammersmith Farm in Newport, Rhode Island.

In 1935, Bouvier was enrolled in Manhattan’s Chapin School, which she attended for grades 1–6. Jacqueline was a bright, curious and occasionally mischievous child. One of her elementary school teachers described her as “a darling child, the prettiest little girl, very clever, very artistic, and full of the devil.” Another teacher, less charmed by young Jacqueline, wrote admonishingly that “her disturbing conduct in geography class made it necessary to exclude her from the room.”

In 1940, at the age of 11, Jacqueline won a national junior horsemanship competition. The New York Times reported, “Jacqueline Bouvier, an eleven-year-old equestrienne from East Hampton, Long Island, scored a double victory in the horsemanship competition. Miss Bouvier achieved a rare distinction. The occasions are few when the same rider wins both competitions in the same show.”

After six years at Chapin, Bouvier attended the Holton-Arms School in Northwest Washington, D.C. from 1942 to 1944, and Miss Porter’s School in Farmington, Connecticut, from 1944 to 1947. She chose Miss Porter’s because it was a boarding school that allowed her to distance herself from the Auchinclosses and because the school placed an emphasis on college preparatory classes. In her senior class yearbook, Bouvier was acknowledged for “her wit, her accomplishment as a horsewoman, and her unwillingness to become a housewife”. Jacqueline later hired her childhood friend Nancy Tuckerman to be her Social Secretary at the White House. She graduated among the top students of her class and received the Maria McKinney Memorial Award for Excellence in Literature.

In 1947, Jacqueline enrolled at Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York. During her junior year abroad, while studying at the Sorbonne, she polished her French and solidified her affinity for French culture and style, which she sometimes associated with her adored father. She graduated from George Washington University in 1951 and took a job as a reporter-photographer at the Washington Times-Herald. She notably covered the coronation (1952) of Elizabeth II.

Jacqueline spent her junior year studying abroad in Paris. “I loved it more than any year of my life,” Onassis later wrote about her time there. “Being away from home gave me a chance to look at myself with a jaundiced eye. I learned not to be ashamed of a real hunger for knowledge, something that I had always tried to hide, and I came home glad to start in here again but with a love for Europe that I am afraid will never leave me.”

Also during her senior year, in 1947, Jacqueline was named “Debutante of the Year” by a local newspaper. However, Onassis had greater ambitions than being recognized for her beauty and popularity. She wrote in the yearbook that her life ambition was “not to be a housewife.”

Personal Life

Jackie was a beautiful and elegant young woman. When she made her social debut, a top newspaper gossip columnist named her Debutante of 1947.

Jacqueline and U.S. Representative John F. Kennedy belonged to the same social circle and were formally introduced by a mutual friend, journalist Charles L. Bartlett, at a dinner party in May 1952. Bouvier was attracted to Kennedy’s physical appearance, charm, wit and wealth. The pair also shared the similarities of Catholicism, writing, enjoying reading and having previously lived abroad. Kennedy was busy running for the U.S. Senate in Massachusetts; the relationship grew more serious and he proposed to her after the November election.

(Jacqueline Lee Bouvier and John F. Kennedy)

They became engaged in June 1953. On September 12, 1953, Jacqueline Lee Bouvier married John F. Kennedy at St. Mary’s Church in Newport, Rhode Island. The wedding was considered the social event of the season with an estimated 700 guests at the ceremony and 1200 at the reception that followed at Hammersmith Farm. The wedding dress, now housed in the Kennedy Library in Boston, Massachusetts, and the dresses of her attendants were created by designer Ann Lowe of New York City.

The early years of their marriage included considerable disappointment and sadness. John underwent spinal surgery, and she suffered a miscarriage and delivered a stillborn daughter. Their luck appeared to change with the birth of a healthy daughter, Caroline Bouvier Kennedy, on November 27, 1957.

In early 1963, Jacqueline was again pregnant, which led her to curtail her official duties. She spent most of the summer at a home she and the President had rented on Squaw Island, which was near the Kennedy compound on Cape Cod, Massachusetts. On August 7 (five weeks ahead of her scheduled due date), she went into labor and gave birth to a boy, Patrick Bouvier Kennedy, via emergency Caesarean section at nearby Otis Air Force Base. The infant’s lungs were not fully developed, and he was transferred from Cape Cod to Boston Children’s Hospital, where he died of hyaline membrane disease two days after birth.

On November 22, 1963, Jacqueline was riding alongside the president in a Lincoln Continental convertible before cheering crowds in Dallas, Texas, when he was shot and killed by Lee Harvey Oswald, widowing Onassis at the age of 34.

After Robert Kennedy’s death, Jacqueline reportedly suffered a relapse of the depression she had suffered in the days following her husband’s assassination nearly five years prior. She came to fear for her life and those of her children, saying: “If they’re killing Kennedys, then my children are targets … I want to get out of this country”.

(Jacqueline and Aristotle Onassis)

In 1968, five years after John F. Kennedy’s death, Jacqueline married a Greek shipping magnate named Aristotle Onassis. However, he died only seven years later, in 1975, leaving Onassis a widow for the second time.

Career and Works

After graduating from college in 1951, Jacqueline landed a job as the “Inquiring Camera Girl” for the Washington Times-Herald newspaper. Her job was to photograph and interview various Washington residents and then weave their pictures and responses together in her column. Among her most notable stories were an interview with Richard Nixon, coverage of President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s inauguration and a report on the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II.

In 1951 Jacqueline met John F. Kennedy, a popular congressman from Massachusetts, and two years later, after he became a U.S. senator, he proposed marriage. On September 12, 1953, the couple wed in St. Mary’s Roman Catholic Church in Newport, Rhode Island. The newlyweds honeymooned in Acapulco, Mexico, before settling in their new home, Hickory Hill in McLean, Virginia, a suburb of Washington, D.C. Kennedy developed a warm relationship with her in-laws, Joseph, and Rose Kennedy.

In January 1960, John F. Kennedy announced his candidacy for the U.S. presidency. Although Jacqueline was pregnant at the time and thus unable to join him on the campaign trail, she campaigned tirelessly from home. She answered letters, gave interviews, taped commercials and wrote a weekly syndicated newspaper column called “Campaign Wife.”

During the 1960 election campaign, Jacqueline hired Letitia Baldrige, who was both politically savvy and astute on matters of etiquette, to assist her as social secretary. Through Baldrige, Jacqueline announced that she intended to make the White House a showcase for America’s most talented and accomplished individuals, and she invited musicians, actors, and intellectuals including Nobel Prize winners to the executive mansion.

Despite not participating on the campaign trail, Jacqueline became the subject of intense media attention with her fashion choices. On one hand, she was admired for her personal style; she was frequently featured in women’s magazines alongside film stars and named as one of the 12 best-dressed women of the world. On the other hand, her preference for French designers and her spending on her wardrobe brought her negative press. In order to downplay her wealthy background, Jacqueline stressed the amount of work she was doing for the campaign and declined to publicly discuss her clothing choices.

As soon as John Kennedy was elected president, Jackie began working to reorganize the White House so that she could turn it into a home for her children and protect their privacy. At the same time, she recognized the importance of the White House as a public institution and a national monument. She formed the White House Historical Association to help her with the task of redecorating the building, as well as a Special Committee for White House Paintings to further advise her. She wrote an introduction to “The White House: A Historical Guide,” and she also developed the idea of a filmed tour of the White House that she would conduct. The tour was broadcast on Valentine’s Day 1962, and it was eventually distributed to 106 countries.

On November 8, 1960, Kennedy defeated Richard Nixon by a razor-thin margin to become the 35th president of the United States; less three weeks later, Onassis gave birth to their second child, John Fitzgerald Kennedy Jr. The couple had a third child, Patrick Bouvier Kennedy born prematurely on August 7, 1963, but lost the child two days later.

Although Jacqueline stated that her priority as a First Lady was to take care of the President and their children, she also dedicated her time to the promotion of American arts and preservation of its history. The restoration of the White House was her main contribution, but she also furthered the cause by hosting social events that brought together elite figures from politics and the arts. One of her unrealized goals was to found a Department of the Arts, but she did contribute to the establishment of the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities, established during Johnson’s tenure.

Jacqueline’s first mission as the first lady was to transform the White House into a museum of American history and culture that would inspire patriotism and public service in those who visited. “Every boy who comes here should see things that develop his sense of history,” she once said. She went to extraordinary lengths to procure art and furniture owned by past presidents including artifacts owned by George Washington, James Madison, and Abraham Lincoln as well as pieces she considered representative of various periods of American culture. “Everything in the White House must have a reason for being there,” she insisted. “It would be sacrilege merely to ‘redecorate’ it a word I hate. It must be restored and that has nothing to do with decoration. That is a question of scholarship.”

During her short time in the White House, Jacqueline became one of the most popular first ladies. During her travels with the president to Europe (1961) and to Central and South America (1962), she won wide praise for her beauty, fashion sense, and facility with languages. Alluding to his wife’s immense popularity during their tour of France in 1961, President Kennedy jokingly reintroduced himself to reporters as the “the man who accompanied Jacqueline Kennedy to Paris.” Parents named their daughters after Jacqueline, and women copied her bouffant hairstyle, pillbox hat, and flat-heeled pumps.

On February 14, 1962, Jacqueline took American television viewers on a tour of the White House with Charles Collingwood of CBS News. In the tour, she stated that “I feel so strongly that the White House should have as fine a collection of American pictures as possible. It’s so important … the setting in which the presidency is presented to the world, to foreign visitors. The American people should be proud of it. We have such a great civilization. So many foreigners don’t realize it. I think this house should be the place we see them best.” The film was watched by 56 million television viewers in the United States and was later distributed to 106 countries. Kennedy won a special Academy of Television Arts & Sciences Trustees Award for it at the Emmy Awards in 1962, which was accepted on her behalf by Lady Bird Johnson. Kennedy was the only First Lady to win an Emmy.

In November 1963 Jacqueline agreed to make one of her infrequent political appearances and accompanied her husband to Texas. The First Lady and the President left the White House for a political trip to Texas; this was the first time that she had joined her husband on such a trip in the U.S. The First Lady was wearing a bright pink Chanel suit and a pillbox hat, which had been personally selected by President Kennedy. As the president’s motorcade moved through Dallas, he was assassinated as she sat beside him; 99 minutes later she stood beside Lyndon Johnson in her blood-stained suit as he took the oath of office, an unprecedented appearance by a widowed first lady.

On her return to the capital, Jacqueline oversaw the planning of her husband’s funeral, using many of the details of Abraham Lincoln’s funeral a century earlier. Her quiet dignity and the sight of her two young children standing beside her during the ceremony brought an outpouring of admiration from Americans and from all over the world.

On November 29, 1963, a week after her husband’s assassination Jacqueline was interviewed in Hyannis Port by Theodore H. White of Life magazine. In that session, she famously compared the Kennedy years in the White House to King Arthur’s mythical Camelot, commenting that the President often played the title song of Lerner and Loewe’s musical recording before retiring to bed. She also quoted Queen Guinevere from the musical, trying to express how the loss felt. The era of the Kennedy administration would subsequently often be referred to as the “Camelot Era,” although historians have later argued that the comparison is not appropriate, with Robert Dallek stating that Kennedy’s “effort to lionize her husband must have provided a therapeutic shield against immobilizing grief”.

It was also Jacqueline who, in the aftermath of the president’s death, provided a metaphor for her husband’s administration that has remained its enduring symbol: Camelot, the idyllic castle of the legendary King Arthur. “There’ll be great presidents again,” She said, “but there’ll never be another Camelot again.”

On January 14, 1964, Kennedy made a televised appearance from the office of the Attorney General; thanking the public for the “hundreds of thousands of messages” she had received since the assassination and said she had been sustained by America’s affection for her late husband. She purchased a house for herself and her children in Georgetown but sold it later in 1964 and bought a 15th-floor penthouse apartment for $250,000 at 1040 Fifth Avenue in Manhattan in the hopes of having more privacy.

In October 1968 Jackie Kennedy married Aristotle Onassis (c. 1900–1975), a wealthy Greek businessman. He was sixty-two and she was thirty-nine. Jackie spent large portions of her time in New York to be with her children. As the years went by, the Onassis marriage was rumored to be a difficult one, and the couple began to spend most of their time apart. Aristotle Onassis died in 1975. His financial legacy was severely limited under Greek law, which dictated how much a non-Greek surviving spouse could inherit. After two years of legal wrangling, Kennedy eventually accepted a settlement of $26 million from Christina Onassis Aristotle’s daughter and sole heir and waived all other claims to the Onassis estate. Widowed for a second time, Jackie returned permanently to New York. For the next two decades, Jackie worked as a book editor for several large publishers in New York City.

Returning to an old interest, Jacqueline worked as a consulting editor at Viking Press and later as an associate and senior editor at Doubleday. She also maintained her interest in the arts and in landmark preservation. Notably, in the 1970s she played an important role in saving Grand Central Terminal in New York City. Although her name was linked romantically with different men, her constant companion during the last 12 years of her life was Maurice Tempelsman, a Belgian-born diamond dealer.

Jacqueline resigned from Viking Press in 1977 following the false accusation by The New York Times that she held some responsibility for the company’s publication of Jeffrey Archer novel Shall We Tell the President?, which was set in a fictional future presidency of Ted Kennedy and described an assassination plot against him. Two years later, she appeared alongside her mother-in-law Rose Kennedy at Faneuil Hall in Boston when Ted Kennedy announced that he was going to challenge incumbent president Jimmy Carter for the Democratic nomination for president. She participated in the subsequent presidential campaign, which was unsuccessful.

In the 1970s, Jacqueline led a historic preservation campaign to save from demolition and renovate Grand Central Terminal in New York. A plaque inside the terminal acknowledges her prominent role in its preservation. In the 1980s, she was a major figure in protests against a planned skyscraper at Columbus Circle that would have cast large shadows on Central Park; the project was canceled. A later project proceeded despite protests: a large twin-towered skyscraper, the Time Warner Center, was completed in 2003.

In the early 1990s, Jacqueline supported Bill Clinton and contributed money to his presidential campaign. Following the election, she met with First Lady Hillary Clinton and advised her on raising a child in the White House. In her memoir Living History, Clinton wrote that Onassis was “a source of inspiration and advice for me”. Democratic consultant Ann Lewis observed that Onassis had reached out to the Clintons “in a way she has not always acted toward leading Democrats in the past”.

Jacqueline continues to be regarded as one of the most beloved and iconic first ladies in American history. Throughout her life, she was a ubiquitous presence on lists of the most admired and respected women in the world. Learned, beautiful and eminently classy, Onassis has come to symbolize an entire epoch of American culture. “She epitomized elegance in the post–World War II era,” historian Douglas Brinkley once said. “There’s never been a first lady like Jacqueline Kennedy, not only because she was so beautiful but because she was able to name an entire era ‘Camelot’ … no other first lady in the 20th century will be able to have that aura. She’s become an icon.”

Awards and Honor

In 2011, Jacqueline was ranked in fifth place in a list of the five most influential First Ladies of the twentieth century for her “profound effect on American society”. In 2012, Time magazine included Kennedy on its All-TIME 100 Fashion Icons list.

In 2014, she ranked third place in a Siena College Institute survey, behind Eleanor Roosevelt and Abigail Adams.

In 2015, she was included in a list of the top ten influential U.S. First Ladies due to the admiration for her based around “her fashion sense and later after her husband’s assassination, for her poise and dignity”.

Jacqueline Kennedy was named to the International Best Dressed List Hall of Fame in 1965. Many of her signature clothes are preserved at the John F. Kennedy Library and Museum; pieces from the collection were exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 2001. Titled “Jacqueline Kennedy: The White House Years,” the exhibition focused on her time as a First Lady.

In 2016, Forbes included her on the list 10 Fashion Icons and the Trends They Made Famous.

Death and Legacy

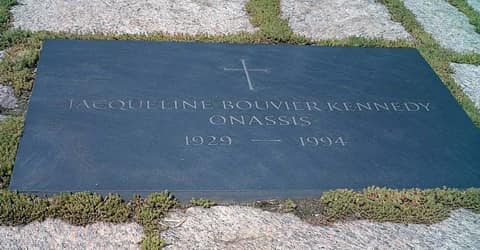

In 1994 Jackie Kennedy told the public that she was being treated for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (a form of cancer), and that her condition was responding well to therapy. However, the disease proved fatal on May 19, 1994, when she died in New York City. After a funeral at St. Ignatius Roman Catholic Church on Park Avenue, she was buried in Arlington National Cemetery beside John F. Kennedy and the two children who had predeceased them. She left an estate that its executors valued at $43.7 million. After her, one surviving son, John F. Kennedy, Jr., was killed in a plane accident in July 1999.

Many books and articles assessed the recurring role of tragedy in the Kennedy story. But it had been a story of luck and glamour as well, and the name she applied to her husband’s short administration, “Camelot,” seemed to capture much of her essence as well.

Jacqueline Kennedy became a global fashion icon during her husband’s presidency. After the 1960 election, she commissioned French-born American fashion designer and Kennedy family friend Oleg Cassini to create an original wardrobe for her appearances as First Lady. From 1961 to 1963, Cassini dressed her in many of her most iconic ensembles, including her Inauguration Day fawn coat and Inaugural gala gown, as well as many outfits for her visits to Europe, India, and Pakistan. In 1961, Kennedy spent $45,446 more on fashion than the $100,000 annual salary her husband earned as president.

As the first lady, Jacqueline was also a great patron of the arts. In addition to the officials, diplomats and statesman who typically populated state dinners, Onassis also invited the nation’s leading writers, artists, musicians and scientists to mingle with its top politicians. The great violinist Isaac Stern wrote to Onassis after one such dinner, “It would be difficult to tell you how refreshing, how heartening it is to find such serious attention and respect for the arts in the White House. To many of us, it is one of the most exciting developments on the present American cultural scene.”

Information Source: