Full name: Booker Taliaferro Washington

Date of birth: April 5, 1856

Place of birth: Hale’s Ford, Virginia, U.S.

Date of death: November 14, 1915 (aged 59)

Place of death: Tuskegee, Alabama, U.S.

Occupation: Educator; Author; African American civil rights leader

Political party: Republican

Father: Washington Ferguson

Mother: Jane Ferguson

Spouse: Fannie N. Smith (1882–1884, her death); Olivia A. Davidson (1886–1889, her death); Margaret Murray (1893–1915, his death)

Children: Booker T. Washington Jr., Ernest Davidson Washington, Portia M. Washington

Early Life

American educator and orator Booker T. Washington, whose full name was Booker Taliaferro Washington, was born on April 5, 1856, and died on November 14, 1915. He founded the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute in Alabama, which is today known as Tuskegee University. Washington dominated both the African-American community and the modern black aristocracy from 1890 and 1915.

Washington had a very challenging upbringing; as a young child, he was made to labor extremely hard and was frequently beaten. He was born to a black slave mother and an unidentified white father. He would see white students at school and want to learn, but it was against the law for slaves to attend school. As one of the founding members of the National Negro Business League, Washington was a strong supporter of African-American-owned enterprises.

Even when his family was freed, poverty prohibited him from continuing his education, forcing him to look for work. However, he was saved by Viola Ruffner, the employer, who pushed him to pursue his education. He finally enrolled at the Hampton Normal Agricultural Institute, where Samuel Armstrong, the headmaster, became a mentor and had a significant impact on the philosophy of the young George Washington.

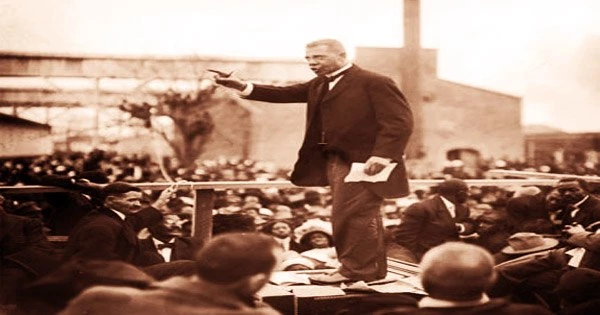

Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft received advice from Washington. Despite his infamous disagreements over segregation with Black leaders like W. E. B. Du Bois, he is now regarded as the most significant African American speaker of his era. With the long-term objective of enhancing the community’s economic power and pride through a focus on self-help and education, Washington rallied a nationwide coalition of middle-class blacks, church leaders, and white donors and politicians.

He gained a great deal of respect within the African-American community after delivering a speech on how education and business may advance the economic and social well-being of black people. Washington supported racial equality through his own donations to the Black community, but he also quietly backed legal challenges to voting restrictions and segregation. Despite his statements that his long-term goal was to abolish the disenfranchisement of African Americans, the vast majority of whom still lived in the South, he received harsh criticism for accommodating white supremacy after his death in 1915.

Childhood and Educational Life

On April 5, 1856, Booker Taliaferro Washington was born in a cabin in Franklin County, Virginia. The proprietor of the plantation employed his mother Jane as a cook. She relocated the family to West Virginia after being free to be with her husband Washington Ferguson. During the Civil War, West Virginia broke away from Virginia and became a free state that joined the Union. Washington started working at the age of nine, first in a coal mine and then in a salt furnace.

Washington’s poverty prevented him from attending school even after he was freed. He supported his family by working as a salt packer in salt furnaces. He enrolled at the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute (now Hampton University) in Virginia in 1872 because he was determined to receive an education and needed the money to cover costs. After earning his degree in 1875, he returned to Malden and taught adults at night and children during school hours for two years. He joined the staff of Hampton after completing his studies at Wayland Seminary in Washington, D.C. (1878–79).

Personal Life

Washington was married three times. In his autobiography Up from Slavery, he gave all three of his wives credit for their contributions at Tuskegee. He married Fannie Smith in 1882 and had one child with her. Fannie died in 1884. His second wife was Olivia Davidson whom he wed in 1885. She gave birth to two sons before dying in 1889.

In 1893 Washington married Margaret James Murray. She was from Mississippi and had graduated from Fisk University, a historically black college. They had no children together, but she helped rear Washington’s three children. Murray outlived Washington and died in 1925.

Working and Political Career

After graduating, Washington worked as a teacher in Malden. In 1878, he enrolled at the Wayland Seminary in Washington, D.C. The youthful Washington was chosen in 1881 to be the founding president of the fledgling Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, which was established to provide higher education for blacks. He built the college from the ground up, involving students in the construction of all types of facilities, including dorms and classrooms. The college work was thought to be essential to students’ overall education.

Initially, Washington himself traveled around advertising the school while sessions were held in a run-down ancient church. The school offered both academic and practical training in trades including printing, farming, carpentry, etc. To honor his life’s effort, Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute was built. At the time of his passing, 34 years later, it had more than 100 modern facilities, 1,500 students, a faculty of close to 200 teaching 38 crafts and professions, and a $2 million endowment.

Washington rose to prominence as an advocate for African-Americans. Black clergymen, teachers, and businesspeople made up his key followers as he developed a statewide network of sympathizers in numerous black areas. He thought that training in industrial and craft skills, as well as the development of the values of perseverance, initiative, and thrift, might serve Black people’s interests in the post-Reconstruction age.

Black people faced several difficulties in the South in the years following Reconstruction. When Jim Crow Laws were in place, discrimination was rampant. Voting under the 15th Amendment was risky, and there were severe restrictions on employment and educational opportunities. The fear of retaliatory violence for promoting civil rights was there with the rise of the Ku Klux Klan. Washington dominated black politics and enjoyed widespread support from both the more liberal whites and the black community in the South (especially rich Northern whites). He was able to interact with prominent national figures in politics, philanthropy, and education.

The Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta, often known as the “Atlanta Compromise” in 1895, invited Washington to speak. He became a prime spokesperson of the African-American community as a result of the speech, which was widely covered by the publications. He exhorted his fellow Blacks, the most of whom were poor and uneducated farm laborers, to temporarily give up their pursuit of complete civil rights and political power in favor of honing their agricultural and industrial abilities in order to secure their financial future.

As part of his efforts, Washington collaborated with white individuals and enlisted the aid of powerful philanthropists. He had claimed that showing “industry, thrift, intelligence, and property” was the best way for black people to obtain equal social rights. His speech was sharply criticized by W.E.B. Du Bois, who repudiated what he called “The Atlanta Compromise” in a chapter of his famous 1903 book, “The Souls of Black Folk.”

Opposition to Washington’s views on race inspired the Niagara Movement (1905-1909). Du Bois would go on to found the NAACP in 1909. He received a White House invitation from President Theodore Roosevelt in 1901. Roosevelt sought advice from Washington on racial issues, as did his successor, President William Howard Taft. In 1901, his autobiography “Up from Slavery” was released. The book detailed his journey from being a slave child to becoming an educator.

Dissenting opinions were vigorously suppressed due to Washington’s disproportionate standing in the Black community. Washington came under fire from Du Bois and others for his harsh handling of competing Black publications and Black intellectuals who dared to disagree with him. Even though he had put a lot of effort towards uplifting black people, Washington came under fire from numerous black activists who believed that black people should be subservient to white people; William Du Bois was his largest detractor.

It is true that rigid patterns of segregation and discrimination institutionalized in the Southern states during the time that Washington rose to prominence as the nation’s voice for African Americans. His race was also systematically denied the right to vote and any meaningful participation in national politics. Even Washington’s visit to the White House in 1901 was greeted with a storm of protest as a “breach of racial etiquette.”

Retirement and Later Life

His autobiography ‘Up from Slavery’ gave a detailed account of the problems faced by blacks during that era and how he overcame the obstacles to succeed in his life. The Modern Library’s list of the top 100 nonfiction books of the 20th century includes the bestseller, which also became a best seller.

He made significant contributions to enhancing the working ties between the races during a trying time of transition. His work significantly aided blacks in obtaining education, wealth, and legal knowledge in the United States. This helped blacks develop the abilities to start and support the civil rights movement, which helped crucial federal civil rights laws get passed in the latter 20th century.

Death and Legacy

Washington’s health was deteriorating rapidly in 1915; he collapsed in New York City and was diagnosed by two different doctors as having Bright’s disease, an inflammation of the kidneys, today called nephritis. He remained at the Tuskegee Institute until congestive heart failure ended his life on November 14, 1915.

His funeral was held on November 17, 1915, in the Tuskegee Institute Chapel. It was attended by nearly 8,000 people. He was buried nearby in the Tuskegee University Campus Cemetery.

Awards and Honours

Washington was awarded an honorary master’s degree from Harvard University in 1896 and an honorary doctorate from Dartmouth College in 1901 for his contributions to American society.

Washington was the first African-American to be depicted on a U.S. postal stamp.

The house where he was born was designated as the Booker T. Washington National Monument on his hundredth birth anniversary.