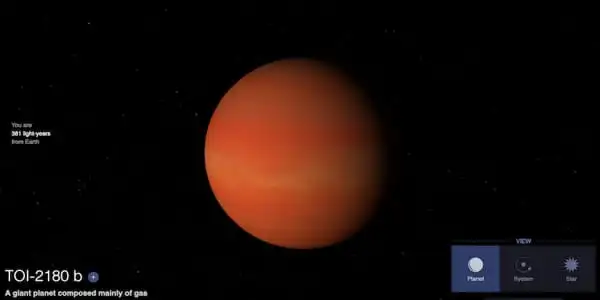

A UC Riverside astronomer and a group of keen citizen scientists have discovered a massive gas planet that was previously hidden from view by standard stargazing tools. TOI-2180 b, a giant gas planet discovered by a UC Riverside astronomer and a group of keen citizen scientists, was recently discovered. The planet was discovered to be a bright, slightly evolved G5 star hidden in plain sight.

TOI-2180 b has the same diameter as Jupiter but is almost three times more massive. It also has 105 times the mass of Earth in elements heavier than helium and hydrogen, according to researchers. Nothing like it can be found in our solar system. The discovery was detailed in the Astronomical Journal and presented at an American Astronomical Society virtual press event.

The planet is relatively close to Earth (379 lightyears) and has an orbit of several hundred days. It is the same size as Jupiter but three times as massive. Scientists estimate that it has 105 times the mass of Earth in elements heavier than helium and hydrogen. Nothing like it can be found in our solar system. TOI-2180 b takes 261 days to orbit its star.

TOI-2180 b is such an exciting planet to have discovered. It satisfies the trifecta of 1) having a several-hundred-day orbit, 2) being relatively close to Earth and 3) being visible to us transiting in front of its star. It is exceedingly rare for astronomers to discover a planet that meets all three of these criteria.

UCR astronomer Paul Dalba

“TOI-2180 b is such an exciting planet to have discovered,” said UCR astronomer Paul Dalba, who contributed to the planet’s discovery. “It satisfies the trifecta of 1) having a several-hundred-day orbit, 2) being relatively close to Earth (379 lightyears is considered close for an exoplanet), and 3) being visible to us transiting in front of its star. It is exceedingly rare for astronomers to discover a planet that meets all three of these criteria.”

Dalba also stated that the planet is unique in that it takes 261 days to complete a journey around its star, which is a relatively long time compared to many other known gas giants outside our solar system. Its proximity to Earth, as well as the brightness of the star it orbits, make it likely that astronomers will be able to learn more about it.

NASA’s TESS satellite looks at one part of the sky for a month before moving on to find exoplanets, which orbit stars other than our sun. It is looking for brightness dips that occur when a planet passes in front of a star.

“The general rule is that we need to see three ‘dips’ or transits before we believe we’ve discovered a planet,” Dalba explained. A single transit event could be caused by a jittery telescope or a star masquerading as a planet. TESS isn’t focused on these single transit events for these reasons. A small group of citizen scientists, on the other hand, is.

Tom Jacobs, a group member and former US naval officer, saw light dim from the TOI-2180 star only once while reviewing TESS data. Dalba, who specializes in studying planets that take a long time to orbit their stars, was alerted by his group.

Dalba and his colleagues observed the planet’s gravitational tug on the star using the Lick Observatory’s Automated Planet Finder Telescope, which allowed them to calculate the mass of TOI-2180 b and estimate a range of orbital possibilities.

Dalba organized a campaign using 14 different telescopes across three continents in the northern hemisphere in the hopes of observing a second transit event. Over the course of 11 days in August 2021, the effort yielded 20,000 images of the TOI-2180 star, but none of them reliably detected the planet.

The campaign did, however, lead the group to estimate that TESS will see the planet transit its star again in February, when a follow-up study is planned. The National Science Foundation’s Astronomy and Astrophysics Postdoctoral Fellowship Program supports Dalba’s research.

The citizen planet hunters group searches for single transit events using publicly available data from NASA satellites such as TESS. While professional astronomers use algorithms to scan large amounts of data automatically, the Visual Survey Group inspects telescope data by eye using a program they created.

“The effort they put in is really significant and impressive, because it’s difficult to write code that can reliably identify single transit events,” Dalba said. “This is one area where humans continue to outperform code.”

The scientists only saw light from the TOI-2180 star once while analyzing TESS data. They then notified Dalba, who is an expert on planets that take a long time to orbit their stars. Dalba and his colleagues searched for the planet’s gravitational pull on the star using the Lick Observatory’s Automated Planet Finder Telescope. This enabled them to calculate the mass of TOI-2180 b as well as a range of orbital possibilities.