Biography of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi – Shah of Iran.

Name: Mohammad Reza Pahlavi

Date of Birth: 26 October 1919

Place of Birth: Tehran, Iran

Date of Death: 27 July 1980 (aged 60)

Place of Death: Cairo, Egypt

Occupation: Shah

Father: Rezā Shāh

Mother: Tadj Ol-Molouk

Spouse/Ex: Fawzia of Egypt (m. 1939; div. 1948), Soraya Esfandiary-Bakhtiari (m. 1951; div. 1958), Farah Diba (m. 1959)

Children: 5

Early Life

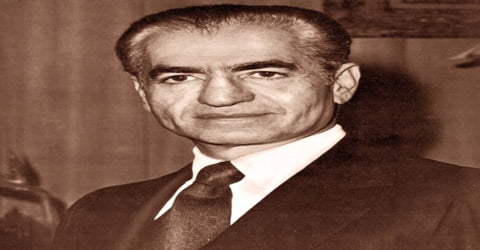

The last Shah of Iran who reigned from 1941 to 1979, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi was born on 26 October 1919, in Tehran, Iran, to Reza Khan (later Reza Shah Pahlavi) and his second wife, Tadj ol-Molouk. Mohammad Reza was the eldest son of Reza Khan, who later became the first Shah of the Pahlavi dynasty and the third of his eleven children. He maintained a pro-Western foreign policy and fostered economic development in Iran. He established many reforms to improve the country, but a revolution, led by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini (1900-1989) in 1979, forced him into exile.

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi was the second and last monarch of the House of Pahlavi. He several other titles, including that of Aryamehr (“Light of the Aryans”) and Bozorg Arteshtaran (“Commander-in-Chief”). His dream of what he referred to as a “Great Civilisation” (Persian: تمدن بزرگ, romanized: tamadon-e bozorg) in Iran led to a rapid industrial and military modernization, as well as economic and social reforms.

During World War II, Mohammad Reza was crowned as the Shah of Iran, at the age of 20, amidst the international political commotion. During his reign, he maintained a pro-Western foreign policy and fostered economic development in Iran. He instituted a ‘White Revolution’ to modernize the country and redistributed extensive land holdings from the wealthiest, dividing them among four million small-holder farmers. He also supported new schools and adult literacy programs in small villages and gave women the right to vote. He sponsored new manufacturing plants and universities in the cities. Corruption in the government and political turmoil resulted in a revolution which forced him to go into exile and was followed by the declaration of an Islamic republic in Iran. He assumed power during the turmoil of World War II, and his rule ended in similarly tumultuous circumstances. He served as the last Shah of Iran ending 2,500 years of monarchy. Due to his status as the last Shah of Iran, he is often known as simply “The Shah”.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi (Persian: محمدرضا پهلوی, pronounced (mohæmˈmæd reˈzɒː ˈʃɒːh pæhlæˈviː); 26 October 1919-27 July 1980), also known as Mohammad Reza Shah (محمدرضا شاه Mohammad Rezā Ŝāh), was born on 26th October 1919, to Reza Pahlavi and his second wife, Tadj ol-Molouk. He was born along with his twin sister, Ashraf. He was the third child and the eldest son of the father’s eleven children from four wives. His father, a former Brigadier-General of the Persian Cossack Brigade, was of Mazandarani and Georgian origin. His mother was an assertive woman who was also very superstitious.

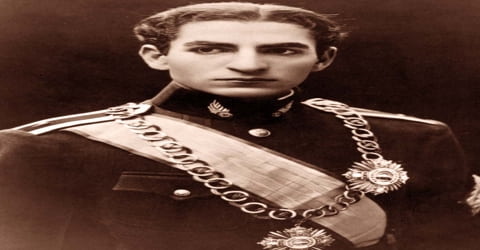

Mohammad Reza was proclaimed crown prince at the age of six. From this time on he was carefully educated for his future role as shah by his stern father. In 1931 he was sent to Switzerland to attend Le Rosey school for boys. He was a good student but made few friends because, as a prince, he was not permitted to leave the school grounds. After returning to Iran in 1936, he entered a Tehran military school, graduating in 1938.

Upon graduating, Mohammad Reza was quickly promoted to the rank of Captain, a rank which he kept until he became Shah. During college, the young prince was appointed Inspector of the Army and spent three years traveling across the country, examining both civil and military installations. Mohammad Reza spoke English, French, and German fluently in addition to his native language Persian.

Personal Life

Mohammad Reza and Princess Fawzia married on 15th March 1939 in the Abdeen Palace in Cairo. Reza Shah did not participate in the ceremony. Dilawar Princess Fawzia of Egypt (5 November 1921-2 July 2013), a daughter of King Fuad I of Egypt and Nazli Sabri, was a sister of King Farouk I of Egypt. They had one child together, Princess Shahnaz Pahlavi, but the couple later got divorced. In his 1961 book Mission For My Country, Mohammad Reza wrote the “only happy light moment” of his entire marriage to Fawzia was the birth of his daughter.

In 1951, Soraya Esfandiary-Bakhtiari, a half-German half-Iranian woman, became his second wife. However, when it became apparent that even with help from medical doctors she could not bear children, he divorced her. However, it was rumored that she was actually 16, the Shah being 32. As a child she was tutored and brought up by Frau Mantel, and hence lacked proper knowledge of Iran, as she herself admits in her personal memoirs, stating, “I was a dunce I knew next to nothing of the geography, the legends of my country, nothing of its history, nothing of Muslim religion.”

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi subsequently indicated his interest in marrying Princess Maria Gabriella of Savoy, a daughter of the deposed Italian king, Umberto II. Pope John XXIII reportedly vetoed the suggestion. In an editorial about the rumours surrounding the marriage of a “Muslim sovereign and a Catholic princess”, the Vatican newspaper, L’Osservatore Romano, considered the match “a grave danger”, especially considering that under the 1917 Code of Canon Law a Roman Catholic who married a divorced person would be automatically, and could be formal, excommunicated.

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi then married Farah Diba and they were blessed with four children; two sons, Prince Reza Pahlavi and Prince Ali-Reza Pahlavi, and two daughters, Princess Farahnaz Pahlavi and Princess Leila Pahlavi.

Career and Works

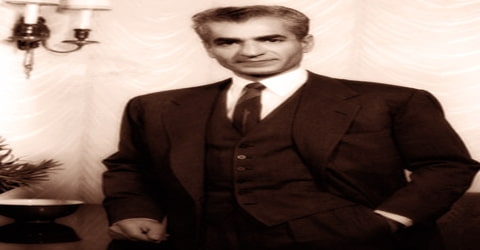

In 1941 the Soviet Union and Great Britain, fearing that the shah would cooperate with Nazi Germany to rid himself of their tutelage, occupied Iran and forced Reza Shah into exile. Mohammad Reza Pahlavi then replaced his father on the throne (September 16, 1941). Mohammad Reza took the oath of office and was received warmly by parliamentarians. On his way back to the palace, the streets filled with people welcoming the new Shah jubilantly, seemingly more enthusiastic than the Allies would have liked. The British would have liked to put a Qajar back on the throne, but the principal Qajar claimant to the throne was Prince Hamid Mirza, an officer in the Royal Navy who did not speak Persian, so the British had to accept Mohammad Reza as Shah.

When Reza Shah sought his assistance to ensure that the Allies would not put an end to the Pahlavi dynasty, Foroughi put aside his adverse personal sentiments for having been politically sidelined since 1935. The Crown Prince confided in amazement to the British Minister that Foroughi “hardly expected any son of Reza Shah to be a civilized human being”, but Foroughi successfully derailed thoughts by the Allies to undertake a more drastic change in the political infrastructure of Iran.

The young Shah was caught in a struggle between the pro-Soviet Tudeh Party, which wanted a social revolution without the shah, and the pro-British National Will Party, which wanted the Shah but no social change. The Shah himself was not satisfied with either idea. After World War II the Soviet Union refused to remove its forces from Iran as it had promised. Instead, the Soviet forces stayed to help a branch of the Persian Communist Party set up a separate government in the northwest province of Azerbaijan. Iran brought this issue to the United Nations (UN). After much discussion, the Soviet Union left Azerbaijan in May 1946, and the Shah became very popular.

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi had serious misgivings about not only the course and roughshod political means adopted by his father but also his unsophisticated approach to affairs of state. The young Shah possessed a decidedly more refined temperament, and amongst the unsavory developments that “would haunt him when he was king” were the political disgrace brought by his father on Teymourtash; the dismissal of Foroughi by the mid-1930s. An even more significant decision that cast a long shadow was the disastrous and one-sided agreement his father had negotiated with the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC) in 1933, one which compromised the country’s ability to receive more favorable returns from oil extracted from the country.

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi was relieved when the Red Army pulled out of Iran, in June 1946. In a letter to the Azerbaijani Communist leader Ja’far Pishevari, Stalin stated that he had to pull out of Iran as otherwise, the Americans would not pull out of China, and he wanted to assist the Chinese Communists in their civil war against the Kuomintang. However, the Pishevari regime remained in power in Tabriz, and Mohammad Reza sought to undercut Qavam’s attempts to make an agreement with Pishevari as a way of getting rid of both. On 11th December 1946, the Iranian Army led by the Shah in person entered Iranian Azerbaijan and the Pishevari regime collapsed with little resistance, with most of the fighting occurring between ordinary people who attacked functionaries of the Pishevari regime who had behaved brutally.

A struggle for control of the Iranian government developed between the shah and Mohammad Mosaddeq, a zealous Iranian nationalist, in the 1950s. Mosaddeq secured passage of a bill in the Majles (parliament) to nationalize the vast British petroleum interests in Iran, in March 1951. Mosaddeq’s power grew rapidly, and by the end of April, Mohammad Reza had been forced to appoint Mosaddeq premier. A two-year period of tension and conflict followed. The Shah tried to dismiss Mosaddeq but was himself forced to leave the country by Mosaddeq’s supporters, in August 1953. Several days later, however, Mosaddeq’s opponents, with the covert support and assistance of the United States and the United Kingdom, restored Mohammad Reza to power.

When 12 university professors issued a public statement criticizing the 1953 coup, all were dismissed from their jobs, but in the first of his many acts of “magnanimity” towards the National Front, Mohammad Reza intervened to have them reinstated, in 1954. Mohammad Reza tried very hard to co-opt the supporters of the National Front by adopting some of their rhetoric and addressing their concerns, for example declaring in several speeches his concerns about the Third World economic conditions and poverty which prevailed in Iran, a matter that had not much interested him before.

Under Mohammad Reza, the nationalization of the oil industry was nominally maintained, although in 1954 Iran entered into an agreement to split revenues with a newly formed international consortium that was responsible for managing production. With U.S. assistance Mohammad Reza then proceeded to carry out a national development program, called the White Revolution, that included construction of an expanded road, rail, and air network, a number of dam and irrigation projects, the eradication of diseases such as malaria, the encouragement and support of industrial growth, and land reform. He also established a literacy corps and a health corps for the large but isolated rural population. New industries were created, and Iran became one of the most stable countries in the Middle East.

Gradually, Mohammad Reza grew increasingly autocratic and took the extreme measure of outlawing all political parties except for his own favored Rastakhiz Party, thus abolishing the multi-party system. Displeased with his rule, his opponents soon began to hold strikes and street rallies to which he responded by deploying the army on the streets of Tehran.

In the 1960s and ’70s, the shah sought to develop a more independent foreign policy and established working relationships with the Soviet Union and eastern European nations. The White Revolution solidified domestic support for Mohammad Reza, but he faced continuing political criticism from those who felt that the reforms did not move far or fast enough and religious criticism from those who believed westernization to be antithetical to Islam. Opposition to the Shah himself was based upon his autocratic rule, corruption in his government, the unequal distribution of oil wealth, forced westernization, and the activities of Savak (the secret police) in suppressing dissent and opposition to his rule. These negative aspects of the shah’s rule became markedly accentuated after Iran began to reap greater revenues from its petroleum exports beginning in 1973.

An attempt on the Shah’s life occurred on 10th April 1965. A soldier shot his way through the Marble Palace. The assassin was killed before he reached the royal quarters, but two civilian guards died protecting the Shah. According to Vladimir Kuzichkin a former KGB officer who defected to the SIS the Soviet Union also allegedly targeted the Shah. The Soviets tried to use a TV remote control to detonate a bomb-laden Volkswagen Beetle; the TV remote failed to function. A high-ranking Romanian defector, Ion Mihai Pacepa, also supported this claim, asserting that he had been the target of various assassination attempts by Soviet agents for many years.

On 27th October 1967, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s forty-eighth birthday, and after twenty-six years as shah, Pahlavi was crowned as His Imperial Majesty Mohammad Reza Pahlavi Aryamehr, Shahanshah of Iran. What made this crowning unique in Persian history was that his third wife, Farah, was crowned as empress, the first since the coming of Islam in the seventh century. Their six-year-old son, Reza, was declared crown prince. During the 1970s, oil-rich countries such as Iran exercised much world power. It was also the strongest military country in the Middle East. However, the Shah ruled with unlimited authority and his popularity began to decrease, especially among Muslims who were followers of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. The Ayatollah led a revolution in 1979, forcing the shah and his family into exile.

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s family traveled to Morocco, the Bahamas, and Mexico within the first six months of exile. Later, he became ill and was granted permission to receive medical treatment in the United States where he spent some time and then went to Egypt. Two weeks later Iranian militants seized the U.S. embassy in Tehrān and took hostage more than 50 Americans, demanding the extradition of the shah in return for the hostages’ release. Extradition was refused, but the Shah later left for Panama and then Cairo, where he was granted asylum by President Anwar el-Sadat.

Awards and Honor

In 1957, Mohammad Reza was decorated with the ‘Grand Collar of the Order of the Yoke and Arrows of Spain’. The same year, he received the ‘Grand Cross w/ Collar of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Italy’. He was knighted with the ‘Order of the Elephant of Denmark’, in 1959. The same year, he also got decorated with the ‘Grand Cross of the Order of the Netherlands Lion’.

In 1960, Mohammad Reza received the ‘Grand Cross of the Order of the Redeemer of Greece’ and the ‘Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold of Belgium’.

On 15 September 1965, Mohammad Reza was granted the title of Aryamehr (‘Light of the Aryans’) by an extraordinary session of the joint Houses of Parliament. He was conferred with the ‘Order of the Flag with Diamonds’ by Hungary and the ‘Grand Cordon of the Grand Star of Yugoslavia’, in 1966.

Death and Legacy

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi underwent treatment in Cairo for non-Hodgkin lymphoma, a type of blood cancer, in March 1980. He died on 27th July 1980 at the age of 60. Egyptian President Sadat gave the Shah a state funeral. In addition to members of the Pahlavi family, Anwar Sadat, Richard Nixon and Constantine II of Greece attended the funeral ceremony in Cairo. Mohammad Reza is buried in the Al Rifa’i Mosque in Cairo, a mosque of great symbolic importance. Also buried there is Farouk of Egypt, Mohammad Reza’s former brother-in-law. The tombs lie to the left of the entrance. Years earlier, his father and predecessor, Reza Shah had also initially been buried at the Al Rifa’i Mosque.

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi introduced a national development program called the ‘White Revolution’ that included the construction of an expanded road, rail, and air network, the encouragement, and support to industrial growth, and land reforms. He also established literacy and health corps for the isolated rural population. In the 1960-70s, he sought to develop a more independent foreign policy and established working relationships with the Soviet Union and eastern European nations.

Shortly after his overthrow, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi wrote an autobiographical memoir Réponse à l’histoire (Answer to History). It was translated from the original French into English, Persian (Pasokh be Tarikh), and other languages. However, by the time of its publication, the Shah had already died. The book is his personal account of his reign and accomplishments, as well as his perspective on issues related to the Iranian Revolution and Western foreign policy toward Iran. He places some of the blame for the wrongdoings of SAVAK, and the failures of various democratic and social reforms (particularly through the White Revolution), upon Amir Abbas Hoveyda and his administration.

Information Source: