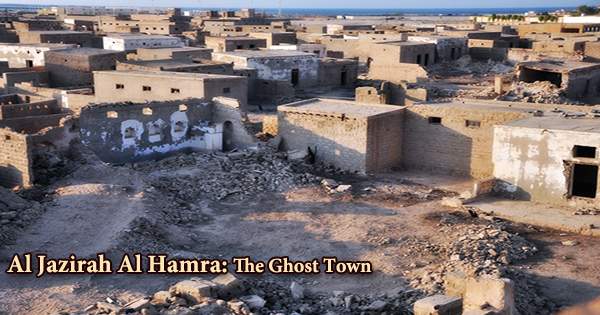

Al Jazirah Al Hamra (Arabic: الجزيرة الحمراء, English: The Red Island) is a surviving emblem of the once-thriving pearl fishing village, whose name in Arabic translates to “Red Island” due to the type of sand used to construct it. It is a town in the United Arab Emirates, located south of the city of Ras Al Khaimah. It’s known for a series of abandoned houses and other structures, including a mosque, that is said to be haunted by locals. Although it is still debatable whether Al Jazirat Al Hamra’s downfall was due to tribal disputes with the Ruler of Ras Al Khaimah or the allure of luxury in Abu Dhabi; a return to this ghost village after the oil was discovered is still a rare experience in knowing how rapidly life changed here. The town began as a tidal island, and by 1830, it had grown to 200 residents, most of whom were engaged in pearl fishing. Rajib bin Ahmed, the Sheikh of Jazira Al Hamra in 1820, was a signatory to the initial 1820 treaty between the Trucial States and the British, which followed the British’s punitive expedition against Ras Al Khaimah in 1819. The sheikhdom was given the name ‘Jourat Al Kamra’ in the treaty. The Ghost Town of Ras Al Khaimah, as it’s known, isn’t exactly on the tourist map, and it’s not on the list of places to demolish to make room for new projects. It’s no surprise, considering that this emirate, known as the “rebel emirate,” isn’t participating in its famous neighbor’s race to build the largest, tallest, or longest of anything.

The Zaab tribe inhabited the former tidal island, which transformed the area into a renowned pearling trade center by 1831. It had over 4,000 residents and hundreds of fishing and trading ships, and thanks to its good fortune, it was able to expand well into the twentieth century. It was divided into two parts, the tiny northern quarter of Umm Awaimir and the southern Manakh because it was a tidal island. Although the Zaab tribe tended groves at Khatt, there were no palm groves at the time, despite having 500 sheep and 150 cattle. Jazirah Al Hamrah had a fleet of 25 pearling vessels, which were the tribe’s main source of income until the pearl market crashed in the late 1920s. Although old towns were repurposed and new cities were established elsewhere in the Gulf, Al Jazirat Al Hamra, now a filled-in patch of land in the south of Ras Al Khaimah, remained deserted and untouched. This abandoned town is now considered one of the best examples of a pre-oil settlement. The structures, like the other pre-oil era structures in the region, were made of coral stones, kept together by mud, and covered with a roof of woven date palms. It’s crazy to think they’ve stood the test of time, surviving hundreds of years of scorching heat, biting sandstorms, and tribal conflicts. The town became part of Ras Al Khaimah after an agreement between Sheikh Khalid bin Ahmad Al Qasimi of Sharjah and Sheikh Sultan bin Salim Al Qasimi of Ras Al Khaimah in 1914, but it was often in dispute with the Ruler. According to others, the prospect of prosperity drew the residents of Al Jazirat Al Hamra to Abu Dhabi. Others speculate that the villagers were forced to seek protection in the land of their neighbors due to a tribal dispute with the Ras Al Khaimah chief. Others say that the occupants were driven away by ghosts haunting the coral-and-mud dwellings. Hussein Bin Rahma Al Zaabi, the last Al-Zaab Sharif (mayor) of Jazirah Al Hamra, later became the Sharif of Abu Dhabi’s Al Zaab district. Rahma, his eldest son, is the ambassador of the United Arab Emirates to Kuwait. The architecture and rows of houses have mostly remained unchanged, and tourists will instantly feel how close-knit and community-spirited this village used to be. The hollow structures, as well as an empty boat and rusting truck referring to the first car in Ras Al Khaimah, are stark reminders of how quickly people left for a new beginning. In 2018, portions of Netflix’s “6 Underground” were filmed in Al Hamra; there are no tour guides, guards, or warning signs. While the fate of the ghost town in Ras Al Khaimah is unknown, its preservation is essential for understanding how a new type of affluence and the birth of a new nation rapidly overturned a once-thriving trading culture and nomadic tradition.