Parkinson’s disease is commonly accompanied by irregularities in sleep cycles and the biological clock. Uncertainty exists regarding the relationship between biological rhythm and neuronal degeneration. Using the fruit fly as a study model, a team from the University of Geneva (UNIGE) has looked at how neurons are destroyed during the day.

The researchers found that the cellular stress associated with Parkinson’s disease was more harmful to neurons at night. The study is published in Nature Communications.

Parkinson’s disease is a neurological ailment that progresses and is defined by the death of specific brain neurons called dopamine neurons. Tremors, sluggishness of movement, and muscle stiffness are the prominent signs of this illness. Epidemiological research suggests that other conditions, like sleep and circadian cycle disruptions, may be linked to this condition.

The human body has an internal clock that regulates practically all of its biological processes. This cycle, which is defined by the alternation of awake and sleep, lasts roughly 24 hours.

In particular, the circadian clock controls the secretion of the “sleep hormone” (melatonin) at the end of the day, variations in body temperature (lower in the early morning and higher during the day), and metabolism in periods of fasting (during sleep) or energy intake (during daytime meals).

Our results further suggest that genetic variations in circadian clock genes may represent a risk factor for dopaminergic neurodegeneration. We now need to ascertain the relevance of these results in humans.

Emi Nagoshi

Cause or consequence?

Disruptions in circadian and sleep rhythms can be observed years before the onset of motor symptoms in Parkinson’s patients. But does disruption of the circadian cycle contribute to the development of the disease, or is it a consequence?

This question is at the heart of work in the laboratory of Emi Nagoshi, associate professor in the Department of Genetics and Evolution at the UNIGE Faculty of Science. Her team uses the fruit fly as a study model for Parkinson’s disease and to dissect the mechanisms of dopamine neuron degeneration.

By subjecting the flies for a few hours to a substance that causes oxidative stress and, in the days that follow, the death of dopaminergic neurons, researchers may replicate the onset of the illness.

Flies’ neurons are more sensitive at night

Despite being very different animals, the biological clocks of flies and humans are comparable. To determine whether the circadian cycle could influence the onset of Parkinson’s disease, flies were exposed to oxidative stress at six different times of the day and night.

“We waited seven days to observe the survival of the targeted neurons under the microscope, and we found a greater number of destroyed dopaminergic neurons when the exposure had been made during the night hours,” explains Michaëla Dorcikova, ex-doctoral fellow in the Department of Genetics and Evolution and first author of the study.

The researchers subjected mutant flies with disrupted circadian cycles to the identical stimuli in order to determine if these observations relied on circadian regularity. The scientists discovered that flies without internal clocks had neurons that were more vulnerable to oxidative stress. These results suggest that the circadian clock exerts a protective effect on dopaminergic neurons against oxidative stress.

Exploring risk factors for Parkinson’s disease

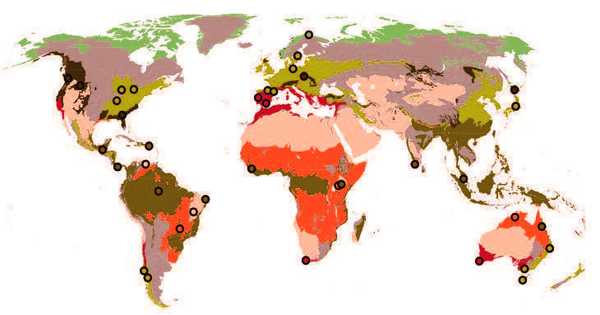

Most Parkinson’s cases result from an interaction between multiple genetic risk factors and lifelong exposure to environmental factors such as pesticides, solvents and air pollution. The findings demonstrate that an oxidative stressor, such as a pesticide, can significantly impact the survival of dopaminergic neurons when it is applied at a certain time of day.

“Our results further suggest that genetic variations in circadian clock genes may represent a risk factor for dopaminergic neurodegeneration. We now need to ascertain the relevance of these results in humans,” concludes Emi Nagoshi, the study’s final author.