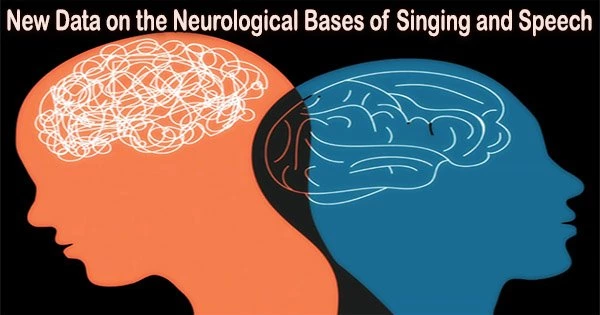

While singing has generally been linked to the structures of both cerebral hemispheres, speech-related neural networks are primarily situated in the left hemisphere. However, a recent study suggests that the left hemisphere is more important than previously believed, notably with regard to singing.

“According to a notion prevalent for more than 50 years, the potential preservation of singing ability in aphasia is based on the fact that the right hemisphere of the brain offers, as it were, a detour to expressing sung words,” says Doctoral Researcher Anni Pitkäniemi from the University of Helsinki.

This hypothesis has also been used as the foundation for the creation of singing-based therapy programs for people who have aphasia, or difficulties speaking as a result of cerebrovascular disease.

However, a study recently published in Communications Biology and carried out by the Cognitive Brain Research Unit at the University of Helsinki found that, contrary to the researchers’ expectations, the ability to produce words by singing was associated not with the structures of the right hemisphere, but as with speech, with the language network of the left hemisphere.

Both shared and distinct neural connections

Another important discovery from the study was that, although the findings show that the language network of the brain plays a central role in both speech and song production, both functions are also partially distributed into separate circuits within that network.

The findings of the recently published study can already help define biological markers that could be useful, for example, in assessing the effectiveness of treatment or rehabilitation. The findings also provide indications of the at least partly parallel development of speech and singing, which is interesting from the perspective of evolutionary neuroscience.

Anni Pitkäniemi

In fact, it was discovered that the ventral stream, which is connected to speech understanding, was responsible for the generation of sung words.

On the other hand, fluent speech was linked in aphasia patients not only to the dorsal stream of the left hemisphere, which is tied to speech production, but also to other connections. These include pathways completely outside of the language network as well as the aforementioned ventral stream, which are more frequently linked to information processing and motor activities in the brain.

“The scale of the network demonstrates the complexity of conversation-level speech,” Pitkäniemi points out.

“The observation also now explains why the ability to produce familiar lyrics is preserved only in certain patients,” she adds. The extent of damage within the language network, she further remarks, has the largest effect on this.

According to Pitkäniemi, the structures of the right hemisphere considered central to singing are likely to play a more important role in other significant factors associated with singing, including the production of melody and rhythm.

Toward increasingly personalized rehabilitation

Researchers have been interested in the connection between music and language for ages.

“There are cases in research literature dating back to the eighteenth century of persons with stroke losing their ability to speak due to aphasia, while unexpectedly retaining the ability to sing the words of familiar songs fluently,” Pitkäniemi says.

The University of Helsinki researchers will then look at the brain networks that are associated with, say, learning new songs or creating melody and rhythm. The idea is to develop increasingly individualized and efficient singing-based rehabilitation techniques for aphasic individuals.

“The findings of the recently published study can already help define biological markers that could be useful, for example, in assessing the effectiveness of treatment or rehabilitation,” Pitkäniemi muses.

“The findings also provide indications of the at least partly parallel development of speech and singing, which is interesting from the perspective of evolutionary neuroscience,” she adds.