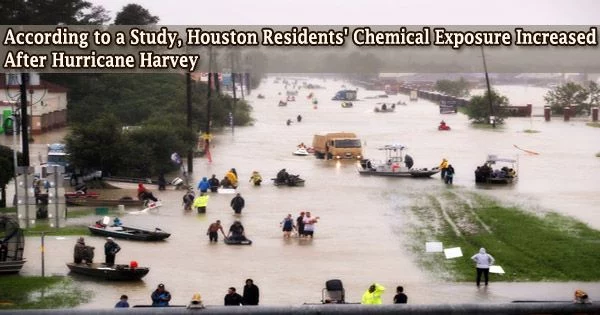

In the wake of Hurricane Harvey in 2017, researchers at Oregon State University utilized silicone wristbands to gauge Houston residents’ heightened exposure to dangerous pollutants.

The wristbands tracked exposure to 162 different chemicals, such as phthalates, flame retardants, industrial chemicals, and pesticides.

Following up with study participants a year after Harvey helped researchers establish a rough baseline that allowed them to identify which exposures were brought on by the storm. Although people’s baseline exposure was already high, 75% of the pollutants tested on average at both timepoints were discovered in higher concentrations right after the hurricane.

“Houston is one of our most industrialized cities,” said co-author Kim Anderson, head of OSU’s Department of Environmental and Molecular Toxicology and the inventor of the study’s wristbands.

“When we look a year after the storm, we see that several neighborhoods that are closer to industrial zones socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods had higher concentrations of chemicals right from the get-go, and that was only exacerbated when the hurricane came in.”

The silicone wristbands serve as a handy screening tool by absorbing toxins from the environment and from skin contact. In comparable studies conducted in South America, Europe, and Africa, Anderson has employed them.

The possible health impacts of many of the substances listed in the Houston study have not yet been adequately investigated, according to researchers. However, exposure to phthalates can have negative effects on reproductive health and some heavier polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons have been found to be carcinogenic.

Houston is one of our most industrialized cities. When we look a year after the storm, we see that several neighborhoods that are closer to industrial zones socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods had higher concentrations of chemicals right from the get-go, and that was only exacerbated when the hurricane came in.

Kim Anderson

After Hurricane Harvey made landfall, the research team got to work almost quickly. Within a week, they received approval for sample, and three weeks later, they gave 173 residents wristbands for the study.

“At that point, flooding was still occurring. I think that’s a huge strength of this study,” said co-author Diana Rohlman, associate professor in OSU’S College of Public Health and Human Sciences. “From the public health perspective, that’s the data people want: ‘I’m actively flooded, actively cleaning my house; what am I being exposed to right now?’”

She stated that this quick reaction is crucial since in the past, during disasters like the 2010 Gulf of Mexico oil leak, catastrophe response times had been delayed by up to six months due to testing permission delays.

Within the first 10 days following Harvey’s impact, the researchers also carried out a short pilot study with 27 residents. Those 27 samples had the largest number of chemicals from any study the researchers have done anywhere else in the world, Anderson said.

The amount of Superfund sites that were harmed by floods following Harvey was a big issue in Houston. Superfund sites are places with pollution levels so high that the EPA has determined they require federal mitigating actions.

70% of Superfund sites nationally are within one mile of federal housing projects, according to a 2020 analysis by the Shriver Center on Poverty Law. This finding highlights the disproportionate burden of pollution placed on low-income areas, most frequently communities of color.

There are nine Superfund sites in the entire state of Oregon, compared to 41 in the city of Houston. 13 of them experienced flooding during the hurricane, but researchers are unsure of the overall impact.

“There is this pocket of contaminants that mobilized in the water, but they were also in five feet of rain, which could be a diluting factor,” Anderson said.

According to Rohlman, 89 industries reported “unintentional emissions” within the first few days of the disaster. Although several industries in Houston shut down after the hurricane, reducing their emissions, the state of Texas also gave manufacturing plants emergency exemptions from clean air laws, so others might have been polluting more, according to researchers.

The bracelets also captured numerous compounds found in typical household cleansers that individuals were exposed to while cleaning their homes after floods, in addition to chemicals released by storm damage.

Rohlman stated that they are unable to provide particular safety advice other than the conventional advice to use gloves and masks when cleaning up flooded areas until more research has been conducted on the individual chemicals listed in the report.

Additional authors on the Houston study were Samantha Samon, Lane Tidwell and Peter Hoffman at OSU and Abiodun Oluyomi at Baylor College of Medicine.