New genetic alterations linked to a subset of canine bladder tumors have been discovered by researchers. Their discoveries have implications for both early cancer detection and targeted treatments in both dogs and humans. The study is published in the journal PLOS Genetics.

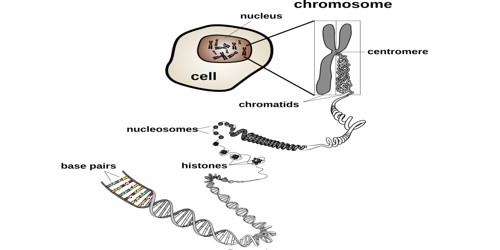

Previous research found that 85% of canine urothelial carcinomas (a kind of bladder cancer) have the same mutation in the BRAF gene. This mutation (known as V595E) is caused by an error in BRAF’s genetic code, where a normal “T” nucleotide in the DNA sequence is substituted by an “A.”

The BRAF V595E mutation causes inappropriate activation of a genetic signaling system known as MAPK, which leads to uncontrolled cellular growth, or proliferation.

“Essentially, BRAF V595E generates an abnormal protein that instructs the cells to keep dividing, forming a tumor. So if this single nucleotide substitution in the BRAF gene is detected in 85% of all canine urothelial carcinomas, why is it not in all of them?” asks Matthew Breen, Oscar J. Fletcher Distinguished Professor of Comparative Oncology Genetics at North Carolina State University and corresponding author of the research. “Pathologists see no difference between those cancers with this mutation and those without, so what’s going on with that other 15%?”

The researchers looked at 28 canine urothelial carcinomas that did not have the BRAF V595E nucleotide substitution, seeking to find other DNA sequence changes that generate these tumors.

Evidence from human cancers suggests that these deletions would generate abnormal proteins that can initiate uncontrolled cellular proliferation and result in a tumor essentially the same end result as V595E. We have developed a laboratory assay that can simultaneously detect both the substitution and deletion mutations, to expand our opportunity for early detection of these cancers in dogs.

Rachael Thomas

The researchers discovered that 13 of the 28 cases (46%) exhibited a different sort of mutation, in which a modest number of nucleotides were deleted, similar to missing words in a phrase. These deletion mutations occurred elsewhere in the BRAF gene or in MAP2K1, another essential MAPK pathway gene.

“This work identified mutations in approximately half of the 15% of canine urothelial carcinomas that don’t have the BRAF V595E mutation,” says Rachael Thomas, lead author of the study. “Evidence from human cancers suggests that these deletions would generate abnormal proteins that can initiate uncontrolled cellular proliferation and result in a tumor essentially the same end result as V595E. We have developed a laboratory assay that can simultaneously detect both the substitution and deletion mutations, to expand our opportunity for early detection of these cancers in dogs.”

But that’s not the only bit of good news. Knowing which mutations are involved in a cancer could lead to more precise, and more effective, treatment.

“We know, for example, that in people with cancers that have a BRAF V600E mutation (the human equivalent of the canine V595E mutation), certain categories of therapeutic drugs are more effective than others,” Breen says. “And human cancers with the corresponding deletion mutations in BRAF and MAP2K1 are more susceptible to a different therapeutic class. So being able to differentiate canine cancers based on their underlying genetic changes may allow us to consider selection of the most appropriate medicine for our dogs in the early stages of the disease.”

The next step for the researchers will be to try to find medications that would effectively target canine bladder tumors with these newly found mutations. They will also look for possible genetic origins of the remaining 7% of canine bladder cancer cases.

“This study drives home the importance of the MAPK pathway in at least 93% of canine bladder cancers,” Breen says. “It will be interesting to see what’s happening in the remaining 7%.”

Surprisingly, whereas dog and human malignancies contain similar mutations, they do not always originate in the same tumor type. For example, while BRAF V595E is common in canine urothelial carcinomas, in people V600E occurs mostly in melanomas.

“This emphasizes the importance of using multiple approaches to studying cancer,” Thomas says. “Looking at which genetic defects are shared by different types of cancer in different species thinking about cancer not just in terms of where in the body it occurs, but also what the cancer DNA itself can tell us. We can think about treatments in those terms as well, which expands opportunities to explore the use of human therapies for dogs with cancer, and vice versa.”