Researchers employed artificial intelligence to explore websites and social media for information on bat hunting and commerce. studies discovered evidence of bat exploitation in 22 nations that had not previously been detected by regular academic studies. Following worries about the IUCN Red List’s dependability, new research shows how AI’s ability to sift massive volumes of web data can benefit wildlife conservation.

Sussex researchers employed artificial intelligence to obtain online records from Facebook, X/Twitter, Google, and Bing in order to map the global scope of bat risks from hunting and trade. The new study shows how social media and internet information provided by news outlets and the general public might help us better comprehend global wildlife issues and refocus conservation efforts.

The Sussex team identified 22 countries involved in bat exploitation, covering both hunting and trade, that had not previously been identified by traditional academic research, including Bahrain, Spain, Sri Lanka, New Zealand and Singapore, which had the highest number of new records.

Using data sources like this provides a low-cost way to help us understand threats to wildlife globally. AI allowed us to access the data at scale and complete a global analysis, which isn’t something we would have been able to achieve using traditional field studies.

Bronwen Hunter

The team created an automated method that enabled them to run large-scale searches on different platforms. They used artificial intelligence to filter through tens of thousands of results in search of useful information. Any observations or anecdotes about bat exploitation were compiled into a global database of ‘bat exploitation records’.

To better identify bat dangers, the team compared online records to academic records, recognizing that data and information published online is influenced by factors such as world events and internet accessibility.

Lead author, Bronwen Hunter at the University of Sussex says:

“Using data sources like this provides a low-cost way to help us understand threats to wildlife globally. AI allowed us to access the data at scale and complete a global analysis, which isn’t something we would have been able to achieve using traditional field studies.

“Another benefit of using online data combined with automated data filtering is that more information can be obtained in real-time, ensuring that we can keep up to date with current threats.”

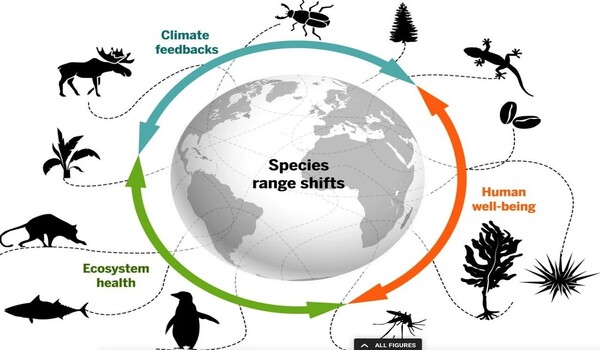

Bats make up about a fifth of all mammal species globally, and have a vital role in ecosystems. They are pollinators, disperse seeds and help with pest control.

The International Union for Nature Conservation (IUCN) classifies over half of bat species as ‘Threatened with Extinction’ or ‘Data Deficient’. There is much less information available about the impact of bat hunting and trade compared to other mammals. Their low reproductive rate and lifespan (typically 10-30 years) render them susceptible on a scale more commonly associated with much larger mammals such as chimps, bears, and lions.

The ability to enhance knowledge of bat exploitation through crowd-sourced digital records can aid in the identification of bat populations in need of conservation intervention, as well as feed into worldwide assessments such as the IUCN Red List.

Prof. Fiona Mathews of the University of Sussex, who leads the research group, states: “The killing and sale of bats for meat was emphasized during the Covid pandemic. However, there is also a serious trade in bats as curios or medicines. It is critical that we determine where bat exploitation occurs, which has previously been difficult because it frequently occurs in rural areas and the illicit trade can be disguised. This study demonstrates that internet and social media posts can give critical evidence that can now be investigated on the ground.”

This research highlights the value of contributions from social media and online platforms and argues that they could be used for future conservation decision making. Using online data combined with current research studies provides a more complete picture of the global extent of bat exploitation.

According to Kit Stoner, CEO of The Bat Conservation Trust, unsustainable wildlife trafficking poses a hazard to bat species that are hunted or harvested. Species are frequently sold far from their original location. This trade has the potential to directly harm bat conservation while also posing a larger concern by raising the risk of zoonotic disease. We applaud the findings of this study because they provide a potential new low-cost method of identifying bat trading, which might be used to monitor how this wildlife trade occurs and investigate strategies to stop it.