You can surely vouch for the truth that seeing loved ones can lift your spirits based on your own personal experience. It’s possible that you’re going through a particularly trying week that’s making it difficult for you to feel optimistic about the future.

How do you cope with these feelings of distress?

It’s likely that you look for a close friend or family member who will be understanding so that you may vent some of that negativity.

The question is, how do you get in touch with this family member?

You may communicate with a family member over a technology gadget rather than in person more frequently in today’s highly mobile environment when people may find it difficult to connect in person. If all goes well, you’ll be able to get in touch on FaceTime or maybe even Zoom. The question is, will that interaction do the trick in helping you feel better?

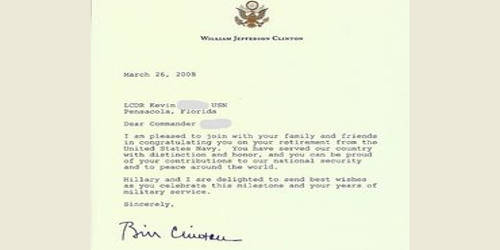

According to a new study headed by the University of Hamburg’s Lara Kroencke (2022), there’s no question that social interaction matters: “A large body of research has shown that… people who interact more than others have higher well-being than average”. The authors argue that as mobile technology develops, the advantages of interaction may not be as evident whether it takes place face-to-face (FtF) or through computer-mediated communication (CMC).

Personality and the Value of Social Interaction

There is no doubt that different people approach social connection from different angles, and as the German authors suggest, personality may very well be one of the factors that determine how social engagement affects a person’s wellbeing. Kroencke et al. used the Five-Factor Model of personality (FFM) to study how each of its sets of attributes affected the interactions that were recorded throughout the day from their college student participants.

Why might personality be so potentially important?

Think now about that scenario in which you sought out your family member for social support. If you’re highly extraverted, you might approach this interaction with the goal of getting things off your chest, looking for what Kroencke and her colleagues refer to as consistent with the “social enhancement hypothesis.” It might not even matter whether you see your relative in person or engage in a CMC type of situation.

However, if you tend toward the neurotic end of the personality trait continuum, you might seek “social compensation.” You might actually benefit more from CMC interactions because you’re worried about your ability to communicate well in person.

The FFM also predicts the potential contribution of other traits to the outcome of FtF versus CMC interactions. People high in the combination of high extraversion along with high agreeableness plus low neuroticism should be the most likely to show benefits of interaction, regardless of the mode. High neuroticism plus low agreeableness and extraversion would, in turn, predict greater benefits from FtF if the social compensation hypothesis is correct.

Testing Personality’s Role in Social Interactions

The German authors set out on the ambitious task of testing their hypotheses on three separate college student samples. They deliberately chose this population because social interactions become so “intense” during the undergraduate years, with many opportunities to connect in both CMC and FtF ways with the people emotionally close to them (such as parents and best friends) and those they know only in a peripheral sense such as classmates. This opportunity, therefore, added the component of closeness to interaction partners as a predictor of well-being from social interaction and personality.

Using experience sampling methodology, Kroencke and her colleagues asked the students (all of whom were attending the University of Texas in Austin) to record their interactions in terms of format and type of partner over a 14-day period. This produced a mammoth 139,363 surveys representing 87,976 different interactions from their more than 3,000 students.

Participants also completed a standard measure of FFM traits along with a simple assessment of their well-being at the time of the interaction. The momentary well-being measures simply asked a set of questions about their mood state as follows: “RIGHT NOW, I am feeling CONTENT/STRESSED/LONELY” in two of the samples, and “angry/worried/happy/sad” in the third.

Getting into the method yourself, try thinking about your last FtF interaction and then the mood that accompanied it. Compare this with your last CMC interaction. The CMC interaction might have occurred through any of a number of modalities; as tested in the German study, they included text messaging, chatting, and interacting on such variations as Instagram, Twitter, Facebook, Snapchat, email, and video. Now think about your mood after the interaction. Was it any different based on the format of your interaction?

Yes, the impact of social interactions is a positive one, Kroencke and her colleagues were able to conclude after doing rigorous statistical analyses on their large database. However, in general, FtF ties with close peers provided the most positive influence.

Relative to CMC interactions, FtF interactions with weak social ties were less likely to produce a positive impact on well-being. Relative to FtF interactions with a close partner, all forms of CMC interaction fell short of the mark, particularly when they involved weak social ties. Any interaction, though, had a more positive effect on well-being compared to no interaction at all.

However, in line with the overall theoretical model informing this study, namely that personality interacts with social factors to influence people’s “momentary thoughts, feelings, and behaviors”, there were moderating effects of FFM traits on the well-being participants reported at the time of the interaction.

Regardless of whom they interacted with, people high in neuroticism benefited from social interactions, even in situations involving a “mixed” FtF and CMC interaction (e.g., texting while in the presence of another person). As the authors concluded, “Thus, our findings suggest that college students high in neuroticism find all social interactions more enjoyable, irrespective of the interaction partner”. As a remedy for loneliness, as the authors propose, social interaction can therefore help serve as a form of compensation for the high levels of worry and depression that the highly neurotic might experience on a chronic basis.

The Need for Social Interaction and Well-Being

The German findings appear to support the lyrics in the song People, that “people who need people are the luckiest people in the world” but also go beyond this sentiment to show why they are so lucky. Wanting to connect to others, particularly for people whose self-doubts and potential loneliness present a risk to mental health, appears to be a healthy and affirmative way to ensure greater well-being.

Returning to the example of seeking support during a stressful time from your family member, you can now see why the ability to connect is so important to your well-being. Moreover, the German findings suggest that the benefit will be particularly positive if you score on the high end of a neuroticism dimension. It might be preferable to ensure that your interaction takes place in person but, if you can’t, the U. Hamburg findings suggest that some form of connection is better than none at all.

To sum up, if fulfillment in life is so contingent on social interactions, the Kroencke et al. study can provide you with inspiration to be one of those “people who need people.”