The soft, gentle murmurs of a baby’s first expressions, like little whispers of joy and wonder to doting parents, are actually signs that the baby’s heart is working rhythmically in concert with developing speech.

Jeremy I. Borjon, University of Houston assistant professor of psychology, is reporting in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that a baby’s first sweet sounds and early attempts at forming words are directly linked to the baby’s heart rate. The findings have implications for understanding language development and potential early indicators of speech and communication disorders.

For infants, producing recognizable speech is more than a cognitive process. It is a motor skill that requires them to learn to coordinate multiple muscles of varying function across their body. This coordination is directly linked to ongoing fluctuations in heart rate.

Borjon investigated whether these fluctuations in heart rate coincide with vocal production and word production in 24-month-old babies. He found that heart rate fluctuations align with the timing of vocalizations and are associated with their duration and the likelihood of producing recognizable speech.

Heart rate naturally fluctuates in all mammals, steadily increasing then decreasing in a rhythmic pattern. It turns out infants were most likely to make a vocalization when their heart rate fluctuation had reached a local peak (maximum) or local trough (minimum).

Jeremy I. Borjon

“Heart rate naturally fluctuates in all mammals, steadily increasing then decreasing in a rhythmic pattern. It turns out infants were most likely to make a vocalization when their heart rate fluctuation had reached a local peak (maximum) or local trough (minimum),” reports Borjon. “Vocalizations produced at the peak were longer than expected by chance. Vocalizations produced just before the trough, while heart rate is decelerating, were more likely to be recognized as a word by naïve listeners.”

Borjon and team measured a total of 2,708 vocalizations emitted by 34 infants between 18 and 27 months of age while the babies played with a caregiver. Infants in this age group typically don’t speak whole words yet, and only a small subset of the vocalizations could be reliably identified as words by naive listeners (10.3%). For the study, the team considered the heart rate dynamics of all sounds made by the baby’s mouth, be it a laugh, a babble or a coo. “Every sound an infant makes helps their brain and body learn how to coordinate with each other, eventually leading to speech,” Borjon said.

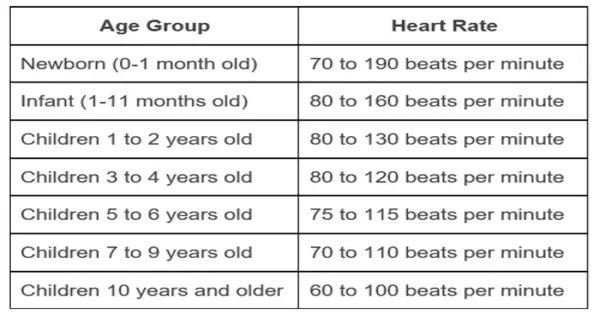

As infants grow, their autonomic nervous system — the part of the body that controls functions like heart rate and breathing — grows and develops. The first few years of life are marked by significant changes in how the heart and lungs function, and these changes continue throughout a person’s life.

“The relationship between recognizable vocalizations and decelerating heart rate may imply that the successful development of speech partially depends on infants experiencing predictable ranges of autonomic activity through development. Understanding how the autonomic nervous system relates to infant vocalizations over development is a critical avenue of future research for understanding how language emerges, as well as risk factors for atypical language development,” said Borjon