Endocrine-disrupting chemicals such as PFAS and phenols have been linked to hormone-mediated malignancies of the breast, ovaries, skin, and uterus. Researchers reviewed NHANES data to learn more about the environmental exposures experienced by women who had these cancers and discovered that women who reported having cancer had much greater amounts of these chemicals in their bodies.

Researchers discovered that persons who had malignancies of the breast, ovarian, skin, and uterus have much greater levels of these chemicals in their bodies, indicating that exposure to certain endocrine-disrupting substances may be playing a role.

While this study does not establish that exposure to chemicals such as PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl compounds) and phenols (including BPA) caused these cancer diagnoses, it does provide a strong indication that they may have played a role and should be investigated further.

Higher exposure to PFDE, a long-chained PFAS compound, was shown to double the odds of a previous melanoma diagnosis in women; higher exposure to two other long-chained PFAS compounds, PFNA and PFUA, nearly doubled the risks of a prior melanoma diagnosis in women.

As communities across the country grapple with PFAS contamination, this adds more evidence to support policymakers in developing action to reduce PFAS exposure. Because PFAS are made up of thousands of chemicals, one way for the EPA to reduce exposure is to regulate PFAS as a class of chemicals rather than one at a time.

Tracey J. Woodruff

The study found a link between PFNA and a prior uterine cancer diagnosis, and women who were exposed to more phenols, such as BPA (used in plastics) and 2,5-dichlorophenol (a chemical used in dyes and found as a by-product in wastewater treatment), had a higher risk of ovarian cancer.

Researchers from UC San Francisco (UCSF), USC, and the University of Michigan collaborated on the study, which was supported by the National Institutes of Health’s Environmental Health Sciences Core Centers.

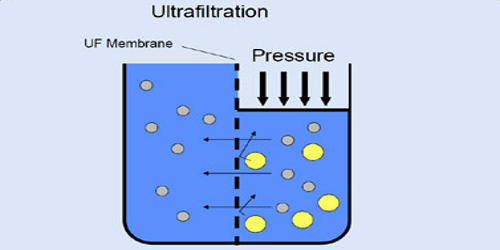

They analyzed data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), which included blood and urine samples from over 10,000 people. They examined current phenol and PFAS exposure in connection to prior cancer diagnoses, as well as racial/ethnic differences in these correlations.

The findings were published in the journal Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiology.

“These findings highlight the need to consider PFAS and phenols as whole classes of environmental risk factors for cancer risk in women,” said Max Aung, Ph.D., senior author of the study and associate professor of environmental health at the USC Keck School of Medicine.

PFAS are ubiquitous in the environment

PFAS have contaminated water, food, and people through products such as Teflon pans, waterproof clothing, stain-resistant carpets and fabrics, and food packaging. They are often referred to as “forever chemicals” because they are resistant to breaking down and therefore last for decades in the environment. PFAS also remain in people’s systems anywhere from several months to years.

“These PFAS chemicals appear to disrupt hormone function in women, which is one potential mechanism that increases the odds of hormone-related cancers in women,” said Amber Cathey, Ph.D., study lead author and research faculty scientist at the University of Michigan’s School of Public Health.

The investigation also discovered racial disparities. Only white women had links with various PFAS and ovarian and uterine malignancies, while non-white women had associations with a PFAS called MPAH and a phenol called BPF with breast cancer.

According to researchers, the EPA should regulate PFAS as a chemical class.

“As communities across the country grapple with PFAS contamination, this adds more evidence to support policymakers developing action to reduce PFAS exposure,” said Tracey J. Woodruff, Ph.D., MPH, UCSF professor and director of the Program on Reproductive Health and the Environment, as well as director of the UCSF EaRTH Center, which funded the study. “Because PFAS are made up of thousands of chemicals, one way for the EPA to reduce exposures is to regulate PFAS as a class of chemicals rather than one at a time.”