Throughout history and throughout continents, every community has had some degree of wealth disparity; there always appear to be those individuals who have more than others. However, the degree of inequality varies by civilization; in some, a few wealthy individuals control practically all of the wealth, whilst in others, money is more evenly distributed.

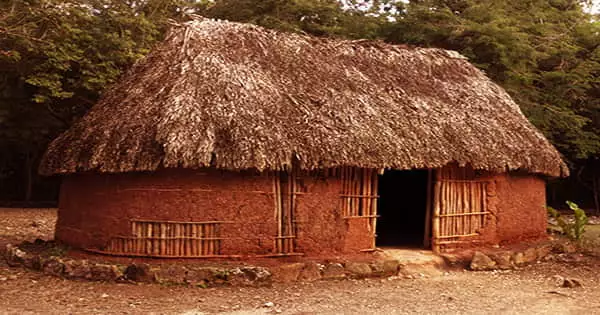

Archaeologists examined the remains of houses in ancient Maya cities and compared them to other Mesoamerican societies in a new study published in PLOS ONE; they discovered that the societies with the most wealth inequality also had governments that concentrated power with a smaller number of people.

“Differences in house size are a reflection of wealth inequality,” says Amy Thompson, a postdoctoral researcher at Chicago’s Field Museum and corresponding author of the PLOS ONE study. “By looking at how house size varies within different neighborhoods within ancient cities, we can learn about wealth inequality in Classic Maya cities.”

Although there are millions of Maya people alive today, scientists date the Classic Maya civilization from 250 to 900 CE. Classic Maya civilization was made up of a network of autonomous communities that spread throughout what is now eastern Mexico, the Yucatan Peninsula, Guatemala, Belize, and western El Salvador and Honduras.

“Rather than being like the United States today where we have one central government overseeing all the states, Classic Maya civilization was a series of cities that each had its own independent ruler,” says Thompson.

People have known for decades, if not centuries, that the Classic Maya were unequal. But the real thing we can add is that this inequality trickled down, even to neighborhoods. That hasn’t really been well documented before.

Keith Prufer

These political systems differed across Mesoamerica, with some sharing power more collectively and others being more authoritarian and concentrating power in a smaller group of individuals. To determine how autocratic a state was, archaeologists analyze a number of indicators.

“We look at the way they represented their leadership. In burials, are certain individuals treated completely differently from everyone else, or are the differences more muted?” says Keith Prufer, an author of the study from the University of New Mexico.

“Another key is to look at palaces. When you have very centralized palace buildings or funerary temples dedicated to a ruling lineage, the government tends to be more autocratic. In societies that were less autocratic, it’s harder to determine where rulers lived or even who they were.”

The researchers aimed to determine how the governmental structure influenced the distribution of income among the population in this study. They point out that wealth disparity is more severe across various social groupings in more authoritarian cultures, as well as amongst people living in the same areas who were previously thought to be economically equal by archaeologists.

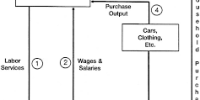

Much of this inequity may be traced back to a lack of access to market products or trading networks. They looked at the ruins of historic dwellings to see how money was distributed among the community.

Home size, for example, does not always reflect wealth; a one-bedroom apartment in Central Park may be valued more than a two-bedroom in Queens, or a complete house in rural Kansas.

“Everything is looked at in a relative sense,” says Gary Feinman, the Field Museum’s MacArthur curator of anthropology and a co-author of the paper. “We’re comparing houses within a neighborhood to each other, and it still reveals a pattern. It would be like if you compared all the houses in Kansas, some might be bigger than the houses in Manhattan, but that relative pattern of wealth distribution in Kansas, as compared to Manhattan, would still tell you something about wealth differentials in both areas.”

To study Maya houses, the researchers looked at a number of variables beyond just size. “Using household archaeology, we can get at the interactions and relationships between the people,” says Thompson. “We document where these houses are on the landscape, how big they are, where they’re located in relationship to each other, and which resources like water and good agricultural land are nearby.”

The researchers also excavated residences to learn about the sorts of pottery and stone tools that the inhabitants used to get more information about wealth distribution.

Even though one district was richer than the other, the researchers discovered that patterns of wealth disparity were rather constant in diverse communities within two Classic Maya settlements in southern Belize. Nonetheless, income disparities were most pronounced in communities having access to trading routes at both sites.

“People have known for decades, if not centuries, that the Classic Maya were unequal,” says Prufer. “But the real thing we can add is that this inequality trickled down, even to neighborhoods. That hasn’t really been well documented before.”

The researchers point out that the correlation between income disparity and despotism isn’t unique to the Classic Maya. “We’re really trying to get at some of these very real issues of how inequality forms, how it’s perpetuated, and how it manifests in early cities,” says Prufer.

“One of archaeology’s bigger aims is to demonstrate that current and ancient cultures are not that unlike in their core features. On many levels, there are many parallels that represent human conduct and creativity, as well as indications of human inequity and cruelty. This comes through from these types of studies, and we feel really good to be able to contribute our work to these broader discussions of social inequality, which are so, so important today.”

While inequality has afflicted mankind for millennia, Feinman believes that as a species, we are not doomed. “There’s a tight interconnection between how power is funded and how power is wielded and monopolized,” he says.

“People can and do establish institutions that try to check power, but it takes work, and it takes interpersonal interdependence and the recognition that we cooperate with communities of people beyond just one’s self and one’s family.”