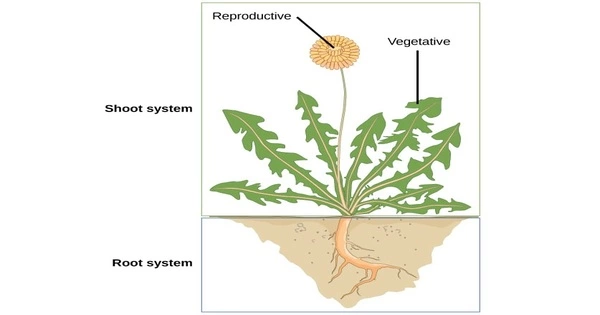

In botany, the root is the underground portion of a vascular plant. Its primary functions are plant anchorage, water and dissolved mineral absorption and transport to the stem, and reserve food storage. The root differs from the stem primarily in the absence of leaf scars and buds, the presence of a root cap, and the presence of branches that grow from internal tissue rather than buds.

Plant roots adapt their shape to maximize water uptake, pausing branching when they lose contact with water and only resuming when they reconnect with moisture, allowing them to survive even in the driest conditions, according to researchers.

Plant scientists at the University of Nottingham have discovered a new water sensing mechanism known as ‘Hydro-Signalling,’ which demonstrates how hormone movement is linked to water fluxes. The findings were published in Science today.

Water is the earth’s rate-limiting molecule. Climate change’s devastation is exacerbating the effects of water scarcity on global agriculture. Rainfall patterns are becoming more erratic as a result of climate change, affecting rain-fed crops in particular.

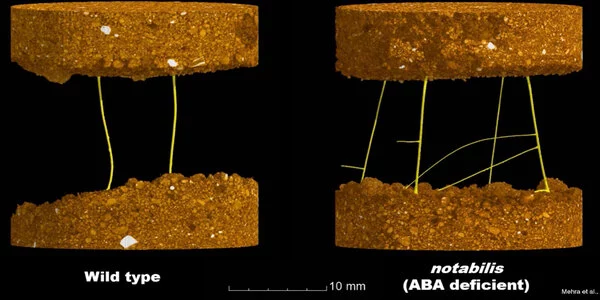

When roots come into contact with water, a key hormone signal (auxin) moves inwards, causing new root branches to form. When roots lose contact with moisture, they rely on internal water sources to mobilize another hormone signal (ABA) outwards, which acts to block the branching signal’s inward movement.

Dr. Poonam Mehra

Roots play an important role in mitigating the effects of water stress on plants by changing their shape (for example, branching or growing deeper) to secure more water. Understanding how plant roots detect and respond to water stress is critical for helping to ‘future proof’ crops and improve their climate resilience.

Researchers used X-ray micro-CT imaging to show that roots change shape in response to external moisture availability by linking water movement with plant hormone signals that control root branching.

The study provides critical information about the key genes and processes controlling root branching in response to limited water availability, helping scientists design novel approaches to manipulating root architecture to enhance water capture and yield in crops.

Roots only grow in length from their tips. The growing tip of the root is protected by a thimble-shaped root cap as it travels through the soil. The apical meristem, a tissue of actively dividing cells, is located just behind the root cap. Some cells from the apical meristem are added to the root cap, but the majority are added to the region of elongation, which is located just above the meristematic region.

One of the lead authors is Dr. Poonam Mehra, a postdoctoral fellow in the School of Biosciences, who explains: “When roots come into contact with water, a key hormone signal (auxin) moves inward, causing new root branches to form. When roots lose contact with moisture, they rely on internal water sources to mobilize another hormone signal (ABA) outward, which acts to block the branching signal’s inward movement. This simple, yet elegant mechanism allows plant roots to fine-tune their shape in response to local conditions and optimize foraging.”

Professor Malcolm Bennett, the study’s co-leader, adds: “Our plant research is critical to understanding how we can future-proof crops and ensure successful crop yields even in the most difficult climates. We are already living in a hotter climate, so designing plants that can still access water in these conditions is critical, and this research is a critical step toward understanding how to do so. These new discoveries were only possible because of the authors’ cutting-edge tools and collaborative approaches, which involved an international team of scientists based in the UK, Belgium, Sweden, the United States, and Israel,” he continued.