A team of Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) researchers created an ionic circuit with hundreds of ionic transistors and performed a core neural net computing process.

Microprocessors in smartphones, computers, and data centers manipulate electrons through solid semiconductors to process information, but our brains use a different system. To process information, they use the manipulation of ions in liquid.

Inspired by the brain, researchers have long been seeking to develop ‘ionics’ in an aqueous solution. While ions in water move slower than electrons in semiconductors, scientists think the diversity of ionic species with different physical and chemical properties could be harnessed for richer and more diverse information processing.

Matrix multiplication is the most prevalent calculation in neural networks for artificial intelligence. Our ionic circuit performs the matrix multiplication in water in an analog manner that is based fully on electrochemical machinery.

Woo-Bin Jung

Ionic computing, however, is still in its early days. To date, labs have only developed individual ionic devices such as ionic diodes and transistors, but no one has put many such devices together into a more complex circuit for computing until now.

A team of researchers at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS), in collaboration with DNA Script, a biotech startup, have developed an ionic circuit comprising hundreds of ionic transistors and performed a core process of neural net computing.

The research is published in Advanced Materials.

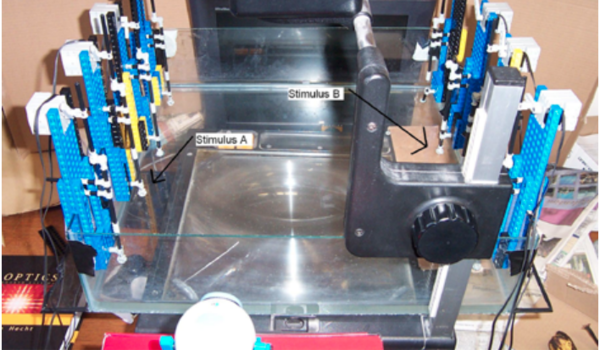

The researchers began by building a new type of ionic transistor from a technique they recently pioneered. The transistor consists of an aqueous solution of quinone molecules, interfaced with two concentric ring electrodes with a center disk electrode, like a bullseye. The two ring electrodes electrochemically lower and tune the local pH around the center disk by producing and trapping hydrogen ions.

A voltage applied to the center disk causes an electrochemical reaction to generate an ionic current from the disk into the water. The reaction rate can be sped up or down by increasing or decreasing the ionic current by tuning the local pH. In other words, the pH controls, or gates, the disk’s ionic current in the aqueous solution, creating an ionic counterpart of the electronic transistor.

They then engineered the pH-gated ionic transistor in such a way that the disk current is an arithmetic multiplication of the disk voltage and a “weight” parameter representing the local pH-gating the transistor. They organized these transistors into a 16 × 16 array to expand the analog arithmetic multiplication of individual transistors into an analog matrix multiplication, with the array of local pH values serving as a weight matrix encountered in neural networks.

“Matrix multiplication is the most prevalent calculation in neural networks for artificial intelligence,” said Woo-Bin Jung, a postdoctoral fellow at SEAS and the first author of the paper. “Our ionic circuit performs the matrix multiplication in water in an analog manner that is based fully on electrochemical machinery.”

“Microprocessors manipulate electrons in a digital fashion to perform matrix multiplication,” said Donhee Ham, the Gordon McKay Professor of Electrical Engineering and Applied Physics at SEAS and the senior author of the paper. “While our ionic circuit cannot be as fast or accurate as the digital microprocessors, the electrochemical matrix multiplication in water is charming in its own right, and has a potential to be energy efficient.”

Now, the team looks to enrich the chemical complexity of the system.

“So far, we have used only 3 to 4 ionic species, such as hydrogen and quinone ions, to enable the gating and ionic transport in the aqueous ionic transistor,” said Jung. “It will be very interesting to employ more diverse ionic species and to see how we can exploit them to make rich the contents of information to be processed.”