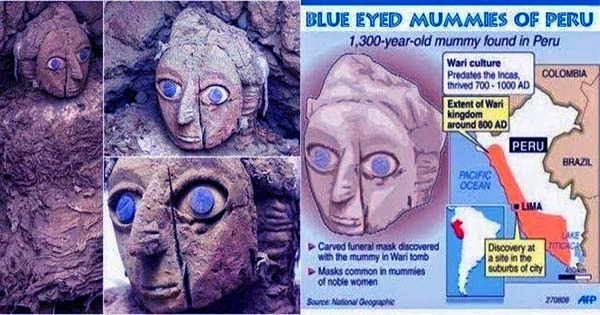

A notable find of seventy-three intact burials in funerary bundles known as ‘fardos’ was made recently at Pachacámac in Peru. The tombs are of both genders, with some ornamented with finely crafted wooden and ceramic masks, specially positioned on ‘fake heads’. The findings are from the late Middle Horizon, circa 800-1100 AD, and correspond to the Wari Empire’s expanding phase.

Contact with Other Empires: Burial and Accompanying Discoveries According to a news release, this archaeological find was discovered by a team of researchers from the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru, led by Professor Krzysztof Makowski, at the archeological site of Pachacámac, located south of Lima, Peru.

In addition to the grave finds, researchers discovered two wooden staffs near the cemetery among the ruins of a nearby village. These staffs were discovered in a deposit of “thorny oyster” (Spondylus princeps) shells, which were thought to have been imported from Ecuador, which is located to the north of the Wari Empire.

The carved iconography on these staffs suggests that the people of Pachacámac had some sort of touch with people from the Tiwanaku kingdom. The Tiwanaku kingdom, located south of the Wari Empire, covered modern-day Peru, Bolivia, and Chile, indicating historic trading networks and cultural contacts.

The wooden staffs portray officials wearing headgear similar to that worn in the Tiwanaku monarchy, offering physical evidence of the influence and exchange between the Pachacámac and Tiwanaku peoples. According to the Archeowiesci blog, the shared aspects in the helmet design, as well as the artistic parallels, make these artifacts historically and culturally unique.

The population that formed as a result of the conquest of the central Peruvian coast around 800 AD coincided with the abandonment of Lima culture temples and power structures dating from 300 to 800 AD. They used ceramics associated with Ayacucho customs. Surprisingly, this pottery also exhibited influences from the northern Peruvian coast, painting a nuanced and diverse picture of cultural interactions during this transitional period.

Pachacámac: Giving Earth Life

During the Wari Empire time, the site had a distinct plan and character that deviated from the assumed ongoing religious use. Pachacámac did not become a monumental edifice until its incorporation into the Inca Empire, when it assumed the role of an oracle, with priests consulting a wooden idol, and became one of the central Andes’ three most important temples.

Notably, Pachacámac lacks the monumental elements seen later during the Wari period. Despite over a century of research, no evidence has emerged to support the hypothesis that the site produced ceramics, textiles, or other artifacts with the intricate iconography of imperial deities seen in Huari, the Wari Empire’s capital, Conchopata (Ayacucho), or Tiahuanaco, the Tiwanaku kingdom’s capital.

Pachacámac is well-known as an Incan-period temple and oracle devoted to the deity Pacha Kamaq (Pachakamak in Quechua), which means ‘one who gives life to the ground,’ and it incorporates a vast complex of cemeteries from various historical periods. Max Uhle, a pioneering figure in scientific archaeology in the Andes, discovered this complex in the late nineteenth century.

Although his exact discoveries were not widely publicized, and only generic descriptions of the site plan, architecture, excavations, and stratigraphy were made available, he linked the temple’s worship to the deity Pacha Kamaq.

The cemetery had been destroyed both before and after Uhle’s research, mostly as a result of colonial efforts to remove pagan beliefs (extirpación de idolatras) and subsequent plundering by grave thieves. As a result, just a percentage of the excavated graves were properly preserved, making these discoveries all the more valuable.

According to Live Science, Professor Makowski and his team, which included Cynthia Vargas, Doménico Villavicencio, and Ana Fernández, intentionally aimed their research efforts at an area where a powerful wall dating back to both the Inca and colonial periods had crumbled.

The motivation behind this approach was the anticipation that the heaps of adobe bricks created by the collapse would act as a barrier, preventing grave thieves from openly reaching the burial places, which proved correct.

The significance and scale of Pachacámac evolved dynamically over time: under the Wari Empire, it appears to have been a rather tiny settlement. However, during the Inca Empire, notably in the 15th century, when Pachacámac witnessed enormous growth, things altered dramatically.

Pachacámac became an important site of religious worship under the Incas. The site’s enlargement and increased religious significance throughout the Inca Empire indicate a dramatic shift in its cultural and geopolitical value.

The Wari Civilization and the Pre-Hispanic Andean Cultural Evolution: The Wari civilization is known for its unique cultural practices and achievements, such as its well-preserved mummies. The Wari people are also noted for their intricate creativity, including finely created pottery and textiles.

The Wari’s cultural environment included rites such as human sacrifice and the usage of hallucinogens during religious ceremonies – a common topic among pre-Columbian indigenous societies, indicating a link between altered states of consciousness and belief systems.

Polish researchers, particularly Professor Miosz Giersz and Patrycja Przdka-Giersz, PhD, who are colleagues and former students of Professor Makowski, have examined the existing site as well as another notable site from the same era, the Castillo de Huarmey on the coast. Drawing parallels between these two sites can help us comprehend this period and the Wari civilization better.

In contrast to Uhle’s earlier views, the cemetery discovered in Professor Makowski’s excavations did not have the characteristics of an elite necropolis. Instead, it resembles the Ancón site, which was renowned as a fishermen’s burial cemetery along the coast between the Chancay and Chillón valleys. This resemblance exists throughout the Wari Empire and the following eras.