Viral Hemorrhagic Fever

Definition

The term “Viral Hemorrhagic Fever” (VHF) is used to describe a severe multisystem syndrome (multisystem in that multiple organ systems in the body are affected). VHF virus infections, particularly those caused by the Ebola and Marburg viruses, can be severe and life-threatening, and are given their name by the fever, exhaustion, and internal bleeding that may occur in its victims. VHF illness in humans is rare worldwide and extremely rare in the United States. Outbreaks of VHF illness are generally found in Africa, South America, and Asia.

Viral Hemorrhagic Fevers (VHFs) refer to a group of illnesses that are caused by several distinct families of viruses. Characteristically, the overall vascular system is damaged, and the body’s ability to regulate itself is impaired. These symptoms are often accompanied by hemorrhage (bleeding); however, the bleeding is it rarely life-threatening. While some types of hemorrhagic fever viruses can cause relatively mild illnesses, many of these viruses cause severe, life-threatening disease.

The Viral Special Pathogens Branch (VSPB) primarily works with hemorrhagic fever viruses that are classified as biosafety level four (BSL-4) pathogens. A list of these viruses appears in the VSPB disease information index. The Division of Vector-Borne Diseases, also in the National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, works with the non-BSL-4 viruses that cause two other hemorrhagic fevers, dengue hemorrhagic fever and yellow fever.

Causes, Sign and Symptoms of Viral Hemorrhagic Fever (VHF)

The viruses that cause viral hemorrhagic fevers live naturally in a variety of animal and insect hosts — most commonly mosquitoes, ticks, rodents or bats.

Each of these hosts typically lives in a specific geographic area, so each particular disease usually occurs only where that virus’s host normally lives. Some viral hemorrhagic fevers also can be transmitted from person to person, and can spread if an infected person travels from one area to another.

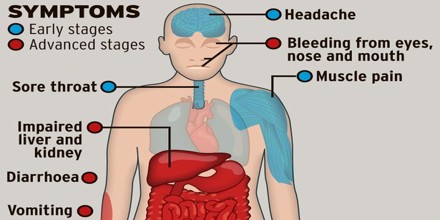

The signs differ depending on the type of Viral Hemorrhagic Fever (VHF) virus. Early on, someone with VHF illness may have a fever (higher than 100.4ºF or 38.0ºC), feel very tired, feel dizzy, have muscle aches, and feel like they have no strength. Unless you have been in an area where people have been sick with VHF, it is unlikely that these symptoms are related to VHF illness. However, signs such as jaundice (yellow skin & eyes), blood in body fluids (urine, vomit, stool), and bleeding from the mouth, eyes, or ears could indicate serious infection related to VHF. Severely ill patient cases may also show shock, nervous system malfunction, coma, delirium, and seizures. Some types of VHF are associated with renal (kidney) failure.

Risk Factors of VHF –

Simply living in or traveling to an area where a particular viral hemorrhagic fever (VHF) is common will increase our risk of becoming infected with that particular virus. Several other factors can increase our risk even more, including:

- Working with the sick

- Slaughtering infected animals

- Sharing needles to use intravenous drugs

- Having unprotected sex

- Working outdoors or in rat-infested buildings

Diagnosis, Treatment and Prevention of VHF

Diagnosing specific viral hemorrhagic fevers in the first few days of illness can be difficult because the initial signs and symptoms — high fever, muscle aches, headaches and extreme fatigue — are common to many other diseases.

Laboratory diagnosis of VHF has traditionally taken place in highly specialized reference laboratories. These laboratories have been classified with biosafety levels (BSL) ranging from 1 to 4 by the World Health Organization. The laboratories are categorized according to the laboratory design, containment facility, and handling of biological agents classified into 4 specific risk groups (RG 1–4).

While no specific treatment exists for most viral hemorrhagic fevers, the antiviral drug ribavirin (Rebetol, Virazole, others) may help shorten the course of some infections and prevent complications in some cases.

Supportive care is essential. To prevent dehydration, you may need fluids to help maintain your balance of electrolytes — minerals that are critical to nerve and muscle function.

Viral Hemorrhagic Fever (VHF) isolation guidelines dictate that all VHF patients should be cared for using strict contact precautions; including hand hygiene, double gloves, gowns, shoe and leg coverings, and faceshield or goggles. Lassa, CCHF, Ebola, and Marburg viruses may be particularly prone to nosocomial (hospital-based) spread. Airborne precautions should be utilized including, at a minimum, a fit-tested, HEPA filter-equipped respirator (such as an N-95 mask), a battery-powered, air-purifying respirator, or a positive pressure supplied air respirator to be worn by personnel coming within 1,8 meter (six feet) of a VHF patient. Multiple patients should be cohorted (sequestered) to a separate building or a ward with an isolated air-handling system. Environmental decontamination is typically accomplished with hypochlorite (e.g. bleach) or phenolic disinfectants.