Ebola Virus Disease and Prevention

Ebola is one of several viruses that can cause Viral Hemorrhagic Fever. The first Ebola virus species was discovered in 1976 in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo, near the Ebola River. Since then, outbreaks have occurred sporadically, mainly in West and Central Africa. Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) has a high mortality rate and there is no treatment proven to be effective, although experimental treatment for EVD is undergoing evaluation.

The most severely affected countries, Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone, have very weak health systems, lack human and infrastructural resources, and have only recently emerged from long periods of conflict and instability. On August 8, the WHO Director-General declared the West Africa outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern under the International Health Regulations (2005).

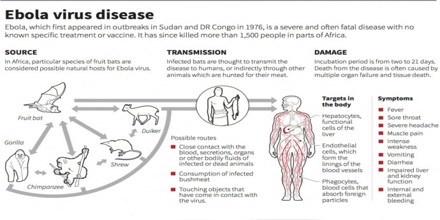

The virus family Filoviridae includes three genera: Cuevavirus, Marburgvirus, and Ebola virus. There are five species that have been identified: Zaire, Bundibugyo, Sudan, Reston and Taï Forest. The first three, Bundibugyo ebola virus, Zaire ebola virus, and Sudan ebola virus have been associated with large outbreaks in Africa. The virus causing the 2014 West African outbreak belongs to the Zaire species.

Health-care workers have frequently been infected while treating patients with suspected or confirmed EVD. This has occurred through close contact with patients when infection control precautions are not strictly practiced.

Key Facts of Ebola Disease

- Ebola virus disease (EVD), formerly known as Ebola haemorrhagic fever, is a severe, often fatal illness in humans.

- The virus is transmitted to people from wild animals and spreads in the human population through human-to-human transmission.

- The average EVD case fatality rate is around 50%. Case fatality rates have varied from 25% to 90% in past outbreaks.

- The first EVD outbreaks occurred in remote villages in Central Africa, near tropical rainforests, but the most recent outbreak in West Africa has involved major urban as well as rural areas.

- Community engagement is key to successfully controlling outbreaks. Good outbreak control relies on applying a package of interventions, namely case management, surveillance and contact tracing, a good laboratory service, safe burials and social mobilization.

- Early supportive care with rehydration, symptomatic treatment improves survival. There is as yet no licensed treatment proven to neutralize the virus but a range of blood, immunological and drug therapies are under development.

- There are currently no licensed Ebola vaccines but 2 potential candidates are undergoing evaluation.

Ebola Virus Disease

Ebola is a deadly disease caused by a virus. There are five strains, and four of them can make people sick. After entering the body, it kills cells, making some of them explode. It wrecks the immune system, causes heavy bleeding inside the body, and damages almost every organ. The virus is scary, but it’s also rare. You can get it only from direct contact with an infected person’s body fluids.

The incubation period, that is, the time interval from infection with the virus to onset of symptoms is 2 to 21 days. Humans are not infectious until they develop symptoms. First symptoms are the sudden onset of fever fatigue, muscle pain, headache and sore throat. This is followed by vomiting, diarrhoea, rash, symptoms of impaired kidney and liver function, and in some cases, both internal and external bleeding. Laboratory findings include low white blood cell and platelet counts and elevated liver enzymes.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing Ebola may be challenging because the early symptoms, such as fever, red eyes and a skin rash, are not specific to Ebola infection and are seen often in patients with more commonly occurring diseases. Confirmation that symptoms are caused by Ebola virus infection are made using the following investigations:

- antibody-capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

- antigen-capture detection tests

- serum neutralization test

- reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay

- electron microscopy

- virus isolation by cell culture.

Samples from patients are an extreme biohazard risk; laboratory testing on non-inactivated samples should be conducted under maximum biological containment conditions.

Prevention, Treatment and Vaccines

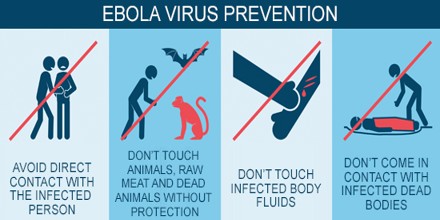

There is as yet no vaccine available to prevent Ebola infection. The aim of all prevention techniques is to avoid contact with the blood or body fluids of infected persons. This includes avoiding travel to areas where Ebola outbreaks are occurring, and taking precautions when providing health care for potentially infectious persons. Precautions may include wearing of protective clothing, such as masks, gloves, gowns, and goggles, using infection-control measures, such as complete equipment sterilization and routine use of disinfectant, and isolating patients with Ebola from contact with unprotected persons. Raising awareness of risk factors for Ebola infection and protective measures that individuals can take is an effective way to reduce human transmission.

Supportive care-rehydration with oral or intravenous fluids- and treatment of specific symptoms, improves survival. There is as yet no proven treatment available for EVD. However, a range of potential treatments including blood products, immune therapies and drug therapies are currently being evaluated. No licensed vaccines are available yet, but 2 potential vaccines are undergoing human safety testing.

Controlling Infection (Ebola Virus)

Health-care workers should always take standard precautions when caring for patients, regardless of their presumed diagnosis. These include basic hand hygiene, respiratory hygiene, use of personal protective equipment to block splashes or other contact with infected materials, safe injection practices and safe burial practices.

Health-care workers caring for patients with suspected or confirmed Ebola virus should apply extra infection control measures to prevent contact with the patient’s blood and body fluids and contaminated surfaces or materials such as clothing and bedding. When in close contact (within 1 metre) of patients with EBV, health-care workers should wear face protection a face shield or a medical mask and goggles, a clean, non-sterile long-sleeved gown, and gloves (sterile gloves for some procedures).

Laboratory workers are also at risk. Samples taken from humans and animals for investigation of Ebola infection should be handled by trained staff and processed in suitably equipped laboratories.