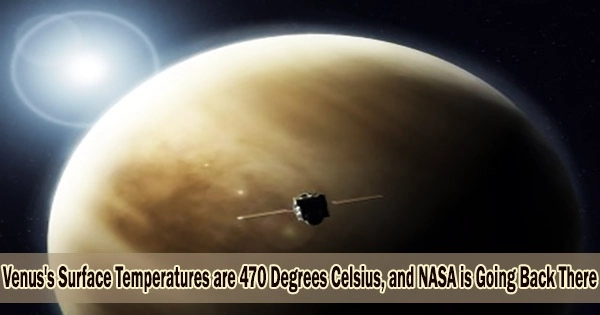

For the purpose of researching the “lost habitable” planet of Venus, NASA has chosen two missions, dubbed DAVINCI+ and VERITAS. The development costs for each mission will be roughly $500 million, and both are planned to launch between 2028 and 2030.

Venus’s incredibly high temperatures led scientists to believe for a long time that there was no life there. But at the end of last year, researchers looking at the planet’s atmosphere made the unexpected (and somewhat contentious) discovery of phosphine. This chemical is predominantly created by living things on Earth.

The information rekindled interest in Earth’s “twin,” inspiring NASA to design cutting-edge missions to study Venus’ planetary environment in greater detail in order to seek for potential signs of life.

Conditions for life

Astronomers have become fixated on looking for exoplanets in other star systems, especially ones that appear habitable, ever since the Hubble Space Telescope revealed the vast quantity of nearby galaxies.

But there are certain criteria for a planet to be considered habitable. It must have a suitable temperature, atmospheric pressure similar to Earth’s and availabile water.

If Venus were outside of our solar system, it probably wouldn’t have drawn as much attention in this aspect. 90% of the country is covered in lava flows, the skies are filled with dense sulfuric acid clouds that are hazardous to people, and the land is a barren landscape of dormant volcanoes.

NASA will nevertheless explore the planet to look for environmental factors that might have once supported life. Any proof that Venus ever had an ocean, in particular, would alter all of our current conceptions of the planet.

Intriguingly, Venus’s climate is noticeably milder 50 kilometers above the planet’s surface. In fact, the pressure decreases so greatly at these greater altitudes that the environment resembles Earth much more, with breathable air and comfortable temperatures.

If life (in the form of microbes) does exist on Venus, this is probably where it would be found.

The DAVINCI+ probe

NASA’s DAVINCI+ (Deep Atmosphere Venus Investigation of Noble gases, Chemistry, and Imaging) mission has several science goals, relating to:

Atmospheric origin and evolution

It will focus on how Venus’ atmosphere first formed, how it evolved, and how (and why) it differs from the atmospheres of Earth and Mars in order to better understand the origins of Venus’ atmosphere.

Atmospheric composition and surface interaction

Understanding Venus’s water history and the chemical reactions taking place in its lower atmosphere will be necessary for this. Additionally, it will look into whether Venus has ever had an ocean. Any search for life would begin here because the waters are where it all began for life on Earth.

Surface properties

This aspect of the mission will provide insights into geographically complex tessera regions on Venus (which have highly deformed terrain), and will investigate their origins and tectonic, volcanic and weathering history.

These findings could shed light on how Venus and Earth began similarly and then diverged in their evolution.

When the DAVINCI+ spacecraft reaches Venus, it will release a spherical probe loaded with delicate equipment into the atmosphere of the planet. The probe will sample the atmosphere as it descends, continuously monitoring the atmosphere while it does so, and sending the measurements back to the orbiting spacecraft.

A mass spectrometer, which can determine the mass of various compounds in a sample, will be carried by the probe. Any noble gases or other trace gases in Venus’ atmosphere will be found using this method.

The dynamics of the atmosphere will also be measured by in-flight sensors, and a camera will capture high-contrast images as the probe descends. Only four spacecraft have ever returned images from the surface of Venus, and the last such photo was taken in 1982.

VERITAS

Meanwhile, the VERITAS (Venus Emissivity, Radio Science, InSAR, Topography, and Spectroscopy) mission will map surface features to determine the planet’s geologic history and further understand why it developed so differently to Earth.

Important details regarding ancient climatic changes, volcanic eruptions, and earthquakes can be found in historical geology. This information can be used to project the size and frequency of potential future events.

Understanding the internal geodynamics that shaped the globe is another goal of the project. To put it another way, we might be able to construct a model of Venus’s continental plate movements and contrast them with those of the Earth.

In parallel with DAVINCI+, VERITAS will take planet-wide, high-resolution topographic images of Venus’s surface, mapping surface features including mountains and valleys.

The Venus Emissivity Mapper (VEM) instrument on board the orbiting VERITAS spacecraft will map gas emissions from the surface at the same time, and it will do so with sufficient precision to be able to identify near-surface water vapor. Because of how powerful its sensors are, they will be able to see through the dense sulfuric acid clouds.

Key insight into conditions on Venus

The most exciting thing about these two missions is the orbit-to-surface probe. Four landers reached Venus’ surface in the 1980s, but they could only stay there for two days because of the intense pressure. There is 93 bar of pressure, which is equivalent to being 900 meters below sea level on Earth.

Then there’s the lava. Many lava flows on Venus stretch for several hundred kilometers. And this lava’s mobility may be enhanced by the planet’s average surface temperature of about 470°C.

While “shield” volcanoes on Venus are only on average about 5.5km high, they are an astonishing 700km wide at the base. Mauna Loa in Hawaii, the largest shield volcano on Earth, has a base that is barely 120 km wide.

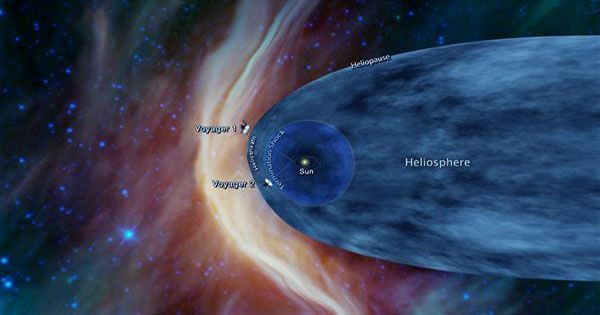

The data from DAVINCI+ and VERITAS will give important insight into how any rocky, life-supporting planet emerges, not just Venus. The ideal outcome of this is to provide us with useful indicators to watch for when looking for habitable worlds outside of our solar system.