In response to the record-breaking marine heatwave that occurred from 2014 to 2016, a new study that was just published in PLOS ONE presents novel documentation of kelp forest degradation along the west coast of the United States and Mexico, as well as proof of local recovery.

The study finds a north-to-south pattern in kelp decline and recovery from the marine heatwave for both giant kelp and bull kelp canopies using Kelpwatch.org, an open-source web tool used to visualize and analyze nearly 40 years of kelp canopy dynamics data derived from satellite imagery.

The study, a collaboration between The Nature Conservancy, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, and the University of California Los Angeles, documents an unprecedented and sustained decline in canopy-forming kelps along the Monterey Peninsula, as well as reasons for hope with recovery in other regions such as Rogue Reef in Oregon and Bahía Tortugas in Mexico.

In western North America, kelp forests cover thousands of kilometers of coastline. But, shifting ocean conditions have caused ecosystems to become unbalanced, which has accelerated the loss of kelp along many coastal sections. According to the latest study, stressor events can affect how canopy-forming kelps react and recover through time and distance.

“The story varies from place to place. Some areas experienced declines, but we are also seeing resilience of kelp forests in other regions. The most important part, though, is that through Kelpwatch.org we can now get this information to managers and stakeholders more effectively to help protect vulnerable regions,” said Dr. Henry Houskeeper, a postdoctoral scholar at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and co-author on the study.

It was surprising to find that not only were there reductions in kelp canopy during the heatwave period, but canopy area continued to decline even after cooler ocean temperatures returned. We were expecting some reductions in kelp canopy, but discovered a greater than 80% loss compared to the historical average across approximately 40 kilometers of coastline from the Monterey Harbor to Carmel Highlands.

Dr. Tom Bell

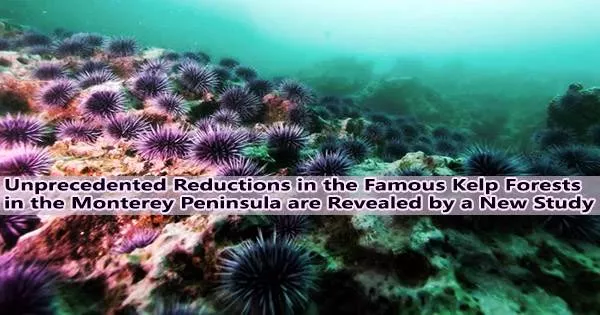

The Monterey Peninsula, one potentially susceptible area, once supported extensive and flourishing kelp forests. However, the aftereffects of the 2014 marine heatwave have led to a reduction in kelp and an increase in the density of native purple urchins, creating “urchin barrens” underwater carpets of urchins that have consumed their food supply and can survive for decades in an undernourished state.

Sea otters, which are known to avoid eating starved urchins from barrens, are a dominant predator of kelp-eating purple sea urchins in the area as a result of the concurrent drop in the population of sunflower sea stars.

“Monterey is the definition of a baseline shifted. It’s like an ecological bomb went off. The old-timers don’t dive here much anymore because it’s too depressing, and us youngsters hold on to documenting the remaining relics of a collapsing kelp cathedral. Everywhere you look, there are ecological outlines of animals that used to live here occupied by creatures imported by warming seas. What if there was a forest fire that burned cold, without flame or smoke? Would anyone notice?” said Patrick Webster an underwater photographer and marine science communicator based out of Monterey Bay, California.

According to a previous study led by Dr. Josh Smith, sea otters maintained the patchy mosaic of kelp forests and purple urchin barrens that had formed around the Monterey Peninsula following the ecosystem collapse that began in 2014. They did this by focusing on well-fed urchins in the kelp patches and avoiding starving urchins from the barrens.

“The new Bell et al. paper indicates that while precipitous declines in kelp may be evidenced across large regions, more nuanced mosaics may develop at smaller spatial scales, especially in places where predators like sea otters alter their foraging behavior in response to sea urchin outbreaks. Importantly, in this system, the remnant patches of kelp forests indirectly maintained by sea otters are crucial for the persistence of giant kelp along the central coast because these remnant forests could provide kelp spores that eventually replenish the barren patches,” said Dr. Smith in response to the new study’s findings.

“Kelp forests around the Monterey Peninsula were some of the most persistent in California,” said Dr. Tom Bell, an assistant scientist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and lead author of the study.

“It was surprising to find that not only were there reductions in kelp canopy during the heatwave period, but canopy area continued to decline even after cooler ocean temperatures returned. We were expecting some reductions in kelp canopy, but discovered a greater than 80% loss compared to the historical average across approximately 40 kilometers of coastline from the Monterey Harbor to Carmel Highlands,” Dr. Bell concluded.

In light of historical and ongoing reductions in this significant ecosystem that provide essential services to both people and environment, the authors of the paper argue for improved data-driven management of kelp forests along their west coast range.

“Our team created Kelpwatch.org to advance state-of-the-art kelp forest monitoring and this study demonstrates how this tool can be used to track near-real-time changes in kelp forest canopy and proactively identify regions experiencing sustained declines fit for management action,” said Vienna Saccomanno, an ocean scientist with The Nature Conservancy who leads the group’s Kelp Mapping and Monitoring Program and is a co-author on the study.