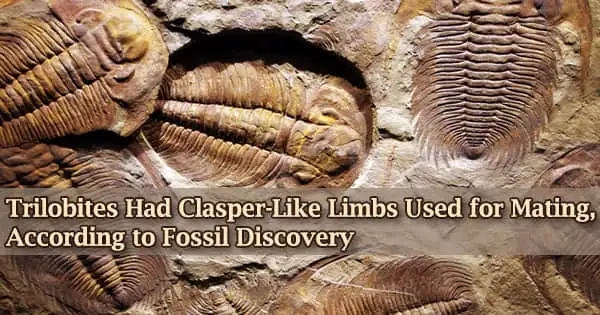

Trilobites predominate the fossil record of early sophisticated animal life in great part because of their exoskeleton’s ease of fossilization. It is challenging to extrapolate the mating and reproductive habits of trilobites since their appendages and the anatomy of the bottom of their bodies are frequently poorly preserved.

Trilobite mating practices have previously been inferred from current arthropods, but a recent study published Friday in Geology detailed the finding of a specialized limb in a mature male trilobite species that provides new insight into the species’ mating behaviors.

Two sets of oddly reduced appendages were discovered in the middle of the body of a fossilized specimen of the trilobite Olenoides serratus. Each of these appendages is thought to be a clasper-like arm that mature males would employ to hold onto females during mating in order to position themselves optimally for external fertilization of the eggs.

“Occasionally you will get fossil specimens that actually died and got preserved in the act of copulation, and there’s a couple of insects that are preserved during mating, but short of that, it’s hard to infer mating behaviors,” said Sarah Losso, lead author of the study.

“There’s about 20,000 described trilobite species, but less than 40 species have preserved appendages. This is the first time that really significant appendage specialization is seen in trilobites. The discovery teaches us more about the behavior of trilobites and shows that this type of complex mating behavior already existed by the mid-Cambrian.”

Trilobites and horseshoe crabs are not particularly closely related to each other, but they share a similar overall organization, and they live in similar marine environments. It’s a little bit like how a bat can fly and a bumblebee can fly. They both use wings, but the wings themselves are quite different in how they are made and how they work. This discovery suggests to some extent that if you are a helmet-looking marine animal that lives on the sediment, there are only so many ways you can effectively mate externally.

Javier Ortega-Hernández

The Burgess Shale in British Columbia, Canada, is a well-known fossil deposit for its soft-bodied preservation of Cambrian animals. It is where the O. serratus fossil specimen, which dates to the Cambrian Period and is about 500 million years old, was originally discovered. The fossil specimen is being kept in Toronto, Canada’s Royal Ontario Museum.

Over 60 trilobite species from the Burgess Shale with preserved appendages were thoroughly examined and documented by Losso. Only one O. serratus specimen had these specially adapted limbs on display.

Losso claims that although the fossil specimen is damaged and is lacking the majority of the exoskeleton that covers the head and half of the body, this allowed researchers to observe the clasper-like limbs that would otherwise have been completely hidden.

The existence of this unique clasper-like appendage in O. serratus or other trilobite species was previously unknown.

Given their similarity in appearance and lifestyle, horseshoe crabs are frequently used as modern analogs for trilobites. This particular trilobite limb appears to function similarly to the claspers that male horseshoe crabs possess and use to hold onto a female’s spines during external fertilization.

This fossil discovery gives evidence for the similarities in their reproductive tactics based on their physical traits, contradicting earlier theories that trilobites had mating behaviors similar to horseshoe crabs.

“Trilobites and horseshoe crabs are not particularly closely related to each other, but they share a similar overall organization, and they live in similar marine environments. It’s a little bit like how a bat can fly and a bumblebee can fly. They both use wings, but the wings themselves are quite different in how they are made and how they work. This discovery suggests to some extent that if you are a helmet-looking marine animal that lives on the sediment, there are only so many ways you can effectively mate externally,” said Javier Ortega-Hernández, co-author of the study.

The finding of this clasper-like limb in trilobites shows that the intricate mating rituals seen in contemporary arthropods date back to the Cambrian Explosion, which took place more than 500 million years ago. It indicates a degree of limb specialization for a non-feeding use and is the earliest instance of an appendage of this type being utilized for reproduction.

“Traditionally, trilobites are looked at as examples of primitive animals. This discovery shows that they could actually display complex behaviors for reproduction, similar to what some of the animals that we have today are doing,” said Ortega-Hernández.

“It is really contributing towards a better understanding of the Cambrian environment as actually being a thriving, ecologically complex system, rather than a lesser version of the biosphere we have today.”