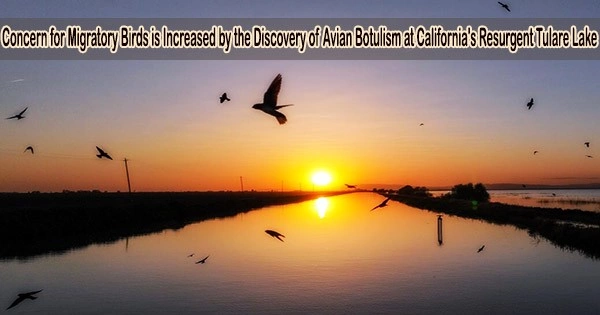

The rising Tulare Lake in California has been found to have avian botulism, which has wildlife authorities worried about possible bird deaths during the fall migration.

The California Department of Fish and Wildlife announced in a news statement on Thursday that testing on a mallard duck and a wading bird called a white-faced ibis taken from the lake in the southern Central Valley revealed the presence of the disease.

Crews are using airboats to collect dead and ill birds.

“Removing carcasses will be the first step of defense in preventing further spread,” department scientist Evan King said in a statement.

The spring snowmelt from the Sierra Nevada supplied Tulare Lake, which was formerly the biggest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi River. However, as people dammed and diverted water for agriculture, turning the lakebed into farmland, the lake gradually disappeared.

The lake reappeared this year after California was hit by an extraordinary series of atmospheric rivers and by May water covered more than 160 square miles (414 square kilometers).

In June, Gov. Gavin Newsom’s office said the water was beginning to recede. The feared flooding of communities was avoided.

The Department of Fish and Wildlife reported that it started air, ground, and water surveys to look for avian botulism owing to stagnant and warming water conditions. Millions of ducks, shorebirds, and other species are anticipated to be drawn to Tulare Lake during migrations.

During a prior reappearance of the lake in 1983, the last significant outbreak of avian botulism at Tulare Lake claimed the lives of roughly 30,000 birds, according to the agency.

Avian botulism causes paralysis and death. It is caused by a naturally occurring toxin-producing bacteria that enters the food chain.

Small outbreaks are common and typically take place in slow-moving parts of rivers and creeks or park ponds, according to the department.

According to the government, the toxin detected in the two birds is one that most usually affects wild birds and is not typically linked to botulism in humans. Bacterial growth is sustained by the decay of dead birds.