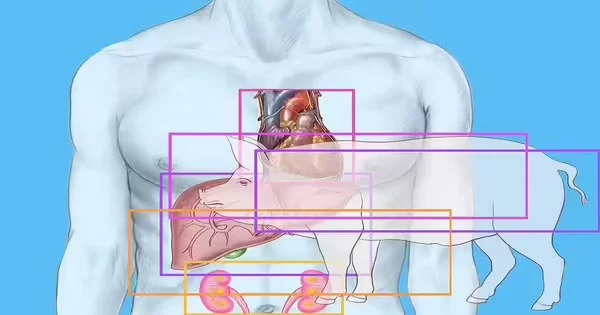

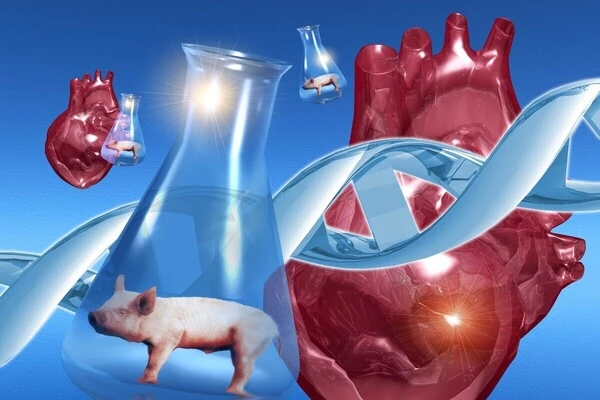

The New York University researchers reported today that they successfully transplanted genetically engineered pig hearts into two recently deceased patients who were connected to ventilators. The surgeries are the latest advancement in the field of animal-to-human transplantation, or xenotransplantation, which has seen a flurry of triumphs this year, raising expectations for a fresh, consistent supply of organs to alleviate shortages.

The only difference between these heart transplants and a standard human-to-human heart transplant, according to the research team, was the organ itself. “Our goal is to integrate the practices used in a typical, everyday heart transplant, only with a nonhuman organ that will function normally without additional aid from untested devices or medicines,” said Nader Moazami, director of heart transplantation at the NYU Langone Transplant Institute.

The transplants were conducted on June 16th and July 9th, and each recipient was observed for three days. The hearts were working correctly at the time, and there were no signals of rejection from the recipients, who were hooked up to ventilators to keep their bodily processes running semi-regularly even after death. Although the two recipients were unable to donate organs, they were able to participate in a whole-body donation for this type of research.

Our goal is to integrate the practices used in a typical, everyday heart transplant, only with a nonhuman organ that will function normally without additional aid from untested devices or medicines.

Nader Moazami

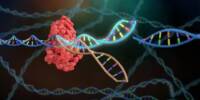

Revivicor, a biotechnology business that manufactures genetically engineered pigs, provided the two pig hearts (and also funded the research). The pigs underwent ten genetic alterations, four of which were to inhibit pig genes and prevent rejection, and six of which were to add human genes.

A living person was successfully given a pig heart, also produced by Revivicor, in early January at the University of Maryland Medical Center. David Bennett Sr., who had severe heart disease, initially responded well to the transplant but died in March of heart failure. The specific cause is still unknown, but infection with a pig virus may have contributed to his death. The pig hearts are supposed to be free of viruses, but experts say they can be hard to detect.

The NYU team said it introduced additional virus screening protocols for its transplants. It also dedicated an operating room to xenotransplantation — that room won’t be used for any other surgical procedures.

Even if a pig heart has already been transplanted into a living human, testing transplants on dead patients is still necessary, according to Robert Montgomery, head of the NYU Langone Transplant Institute, during a news conference. “The emphasis is really on learning, studying, measuring, and attempting to truly untangle what is going on with this fresh new, fantastic technology,” he explained. For example, the team was able to do biopsies on a daily basis. Because the receiver was still alive, the research team at the University of Maryland was unable to investigate the transplant in great detail, he explained.

Brain-dead patients have also been used at NYU to test kidney xenotransplantation. This fall, NYU announced that it successfully attached a pig kidney to the leg of a patient on a ventilator. The patient’s body did not reject the organ, and it functioned normally through 54 hours of observation.

Full clinical trials of xenotransplantation in living persons are currently being planned by research teams. To do so, they’d require clearance from the Food and Drug Administration. Montgomery stated during the press conference that the NYU team’s goal is to extend the period of time they monitor a transplanted heart in order to collect additional data to inform trials. He believes clinical studies will begin between now and 2025. Revivicor stated in April that it expects to begin clinical trials over the next year or two.

There is still much to learn about xenotransplantation, as well as the ethical concerns of animal-to-human treatments. However, if they are successful, they could provide a new option for the thousands of patients on organ transplant waiting lists.

“I feel that xenotransplantation offers the best potential for a renewable, sustainable source of organs, so that no one has to die waiting for an organ,” Montgomery said.