We have a lot of knowledge about insect preferences close up, but how do mosquitoes locate us up to 100 meters away? Researchers in Zambia discovered that human body odor is essential for mosquito host-seeking behavior across great distances using an ice-rink-sized outdoor testing arena.

The group also discovered particular components of airborne body odor that may help to clarify why some people are more attractive to mosquitoes than others. The work appears May 19, 2023, in the journal Current Biology.

The majority of research on mosquito preferences has been done in cramped lab conditions, which is probably not representative of what a mosquito would encounter in the wild.

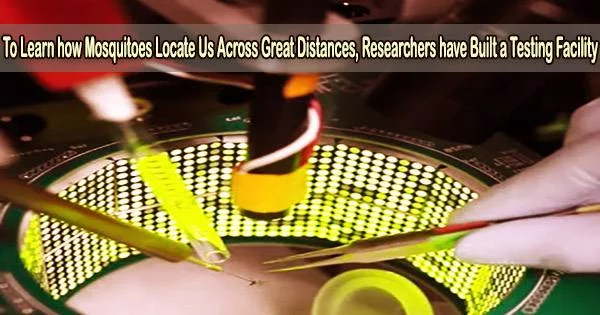

To test how the African malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae locates and chooses human hosts over a large and more realistic spatial scale, researchers from Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health’s Malaria Research Institute and Macha Research Trust teamed up to build a 1,000 m3 testing arena in Choma District, Zambia.

“This is the largest system to assess olfactory preference for any mosquito in the world,” says neuroscientist Diego Giraldo, a postdoctoral fellow at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, one of the study’s first authors. “And it’s a very busy sensory environment for the mosquitoes.”

When you see something moved from a tiny laboratory space where the odors are right there, and the mosquitoes are still finding them in this big open space out in a field in Zambia, it really drives home just how powerful these mosquitoes are as host seekers.

Stephanie Rankin-Turner

A ring of uniformly spaced landing pads that were heated to body temperature (35oC) made up the testing arena. 200 ravenous mosquitoes were put into the testing area each night, and the researchers used infrared motion cameras to observe their behavior. Specifically, they took note of how often mosquitoes landed on each of the landing pads (which is a good sign that they’re ready to bite).

The scientists began by weighing the proportional contributions of heat, CO2, and human body odor in luring insects. They discovered that human body odor was a more alluring bait than CO2 alone since mosquitoes weren’t drawn to the heated landing pads unless they were simultaneously baited with CO2.

Next, the team tested the mosquitoes’ choosiness. For this, they used reused air conditioner ducting to pipe air from each tent holding the scents of its sleeping occupant onto the heated landing pads. They did this by having six people spend six nights sleeping in single-person tents throughout the arena.

The researchers took nightly air samples from the tents to describe and contrast the airborne components of body odor in addition to noting the mosquitoes’ preferences.

“These mosquitoes typically hunt humans in the hours before and after midnight,” says senior author and vector biologist Conor McMeniman, assistant professor at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and Johns Hopkins Malaria Research Institute. “They follow scent trails and convective currents emanating from humans, and typically they’ll enter homes and bite between around 10 PM and 2 AM. We wanted to assess mosquito olfactory preferences during the peak period of activity when they’re out and about and active and also assess the odor from sleeping humans during that same time window.”

They discovered that some people were consistently more attractive to mosquitoes than others, and one volunteer who had an olfactory composition that was noticeably different from the others consistently attracted very few mosquitoes.

The study found that all of the humans released 40 compounds, albeit at varied rates.

“It’s probably a ratio-specific blend that they’re following,” says analytical chemist Stephanie Rankin-Turner, a postdoctoral fellow at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, the study’s other first author. “We don’t really know yet exactly what aspect of skin secretions, microbial metabolites, or breath emissions are really driving this, but we’re hoping we’ll be able to figure that out in the coming years.”

The researchers discovered certain consistent patterns despite the fact that each person’s odor profile changed from night to night. Individuals who were more attractive to mosquitoes routinely released more carboxylic acids, which are likely created by skin microorganisms.

The individual who was least attractive to mosquitoes, on the other hand, released less carboxylic acids but around three times as much eucalyptol, a substance that is present in many plants; the researchers hypothesize that elevated levels of eucalyptol may be connected to the individual’s diet.

The mosquitoes’ ability to distinguish between prospective human meals in the vast arena astounded the researchers.

“When you see something moved from a tiny laboratory space where the odors are right there, and the mosquitoes are still finding them in this big open space out in a field in Zambia, it really drives home just how powerful these mosquitoes are as host seekers,” says Rankin-Turner.