Þingvellir (Icelandic: ˈθiŋkˌvɛtlɪr̥, anglicized as Thingvellir) is historically known to be the place where the first parliamentary assembly of Iceland was formed in the year 930, and was the meeting place of the Parliament for an uninterrupted period of 868 years, until 1798.

There they met from all over the country, people who traveled for up to 17 days to be part of that holiday that was the Parliament meeting, a unique occasion to get drunk and dance with other faces beyond the few that they saw during the long and hard winters.

Þingvellir is now a national park in the municipality of Bláskógabyggð in southwestern Iceland, about 40 km northeast of Iceland’s capital, Reykjavík. Þingvellir is a site of historical, cultural, and geological significance, and is one of the most popular tourist destinations in Iceland. The park lies in a rift valley that marks the crest of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge and the boundary between the North American and Eurasian tectonic plates. To its south lies Þingvallavatn, the largest natural lake in Iceland.

Þingvellir National Park (þjóðgarðurinn á Þingvöllum) was founded in 1930, marking the 1000th anniversary of the Althing. The park was later expanded to protect the diverse and natural phenomena in the surrounding area and was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2004.

The property includes the Þingvellir National Park and the remains of the Althing itself: fragments of around 50 booths built from turf and stone. Remains from the 10th century are thought to be buried underground. The site also includes remains of agricultural use from the 18th and 19th centuries. The park shows evidence of the way the landscape was husbanded over 1,000 years.

It is one of the most sacred places in the country since it began to build the nation and the identity of the Icelandic people, and it was there when in 1944 the country was declared independent. It is also home to Silfra, a once in a lifetime dive and snorkel spot where you can swim between tectonic plates and actually touch Europe and North America at the same time.

The name is most commonly anglicized as Thingvellir and might appear as Tingvellir, Thingvalla, or Tingvalla in other languages. The spelling Pingvellir is also seen, although the letter “p” does not correspond to the letter “þ” (thorn), which is pronounced (θ), like the thin thirst.

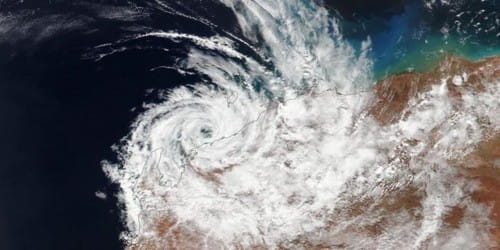

The whole area lies on top of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, an enormous fissure that stretches between the Eurasian and the North American continental plates, extending over 16,000 kilometers (9,950 miles). As a result of the movement of the plates, Iceland experiences increased seismic and volcanic activity.

About 10,000 years ago, after the Langjökull glacier had retreated and reached its current position, a shield volcanic eruption started in the Thingvellir area. This resulted in the formation of some of the most beautiful Icelandic shield volcanoes which today decorate the landscape around the national park. This eruption lasted for decades, maybe even up to a century.

About 3,000 years ago, an 8-kilometer (4.7 miles) long eruptive fissure opened in Thingvellir valley and multiple eruptions followed one after another. The last eruption in the area occurred around 2,000 years ago when an ash crater arose from the bottom of Lake Thingvallavatn. Volcanic activity in the area has been dormant since then, but the question remains not whether but when it will start up again.

In the summer of 2000, two severe earthquakes occurred in South Iceland. Even though their source was 40-50 kilometers (24-31 miles) southeast of Thingvellir, stones fell from the ravine walls and water splashed up from the rifts. The earthquakes were a result of movement in the Eurasian and North American plate boundaries that run through Iceland.

In the south, the plates inch past each other while at Thingvellir, they break apart and the land between them subsides. Away from the plate boundaries, the activity is fairly constant at about two centimeters (0.78 inches) per year. But, in the rift zones themselves, tensional stress accumulates during a long period which is then released in a burst of activity when fracture boundaries are reached.

During the 19th century, Þingvellir emerged as a nationalist symbol. According to Icelandic political scientist Birgir Hermannsson, “Thingvellir can be likened to a church or building which serves as a pilgrimage destination and as a site for the nation-state’s ritual ceremonies.”

The World Heritage property contains the physical remains of the Alþing and its long persistence at Þingvellir. There is a well-known kinship between the Alþing, Þingvellir, and Germanic Law and governance, documented through the Icelandic sagas and the written codification of the Grágás Laws. This closeness was strengthened in the 19th century by the independence movement and a growing appreciation of landscape values and their perceived association with ‘natural’ and ‘noble’ laws. Furthermore, the Alþing is closely linked to its hinterland (now the landscape of the National Park), agricultural land that was traditionally used as grazing grounds for those attending the Alþing, and across which the tracks led to the Assembly grounds. The fossilized cultural landscape of the park reflects the evolution of the farming landscape over the past thousand years, with its abandoned farms, fields, tracks; associations with people and events recorded in place names and archival evidence also document the settlement in Iceland as well as the high natural values of this landscape. The inspirational qualities of Þingvellir’s landscape, derived from its unchanged dramatic beauty, its association with national events and ancient systems of law and governance, have lent the area its iconic status and turned it into the spiritual center of Iceland.

Þingvellir is notable for its unusual tectonic and volcanic environment in a rift valley. The continental drift between the North American and Eurasian Plates can be clearly seen in the cracks or faults which traverse the region, the largest one, Almannagjá, being a veritable canyon. This also causes the often measurable earthquakes in the area.

Some of the rifts are full of clear water. One, Nikulásargjá, was bridged for the occasion of the visit of King Frederick VIII of Denmark in 1907. On this occasion, visitors began to throw coins from the bridge into the fissure, a tradition based on European legends. The bottom has become littered with sparkling coins, and the rift is now better known as Peningagjá, or “coin fissure”.

Þingvellir was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site based on cultural criteria. It may also qualify on geological criteria in the future, as there has been an ongoing discussion of a possible “serial trans-boundary nomination” for the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, which would include other sites in the Atlantic such as Pico Island. Together with the waterfall Gullfoss and the geysers of Haukadalur, Þingvellir is part of a group of the most famous sights of Iceland, the Golden Circle.

Lake Thingvallavatn is particularly fertile and rich in vegetation despite the very cold temperatures. A third of the bottom area is covered by vegetation and there is a large number of algae. Low-growing vegetation extends out to a depth of 10 meters (32.8 feet) while higher-growing vegetation forms a large growing belt from 10-30 meters (32.8-98.4 feet) deep. From the shore to the center of the lake, a total of 150 types of plants have been found as well as 50 kinds of invertebrates. In Lake, Thingvallavatn can be found three of the five species of freshwater fish found in Iceland: brown trout, Arctic char, and the three-spined stickleback. It is said that these fish became isolated in the lake in the wake of the last ice age when the terrain rose at the south end of Thingvallavatn.

Following one of the major earthquakes, a large rift opened overnight next to the Lake Thingvallavatn. The fissure called ‘Silfra’ was not eruptive but soon began to fill with meltwater from Langjökull glacier, which lies about 50 kilometers (31 miles) away.

As the water travels through a dense lava field, it gets purified by the finest natural filtration on the planet. Lava rock has an extremely very fine texture. It takes the glacial water about 30 to 100 years to reach its final destination in the Silfra fissure. The result is that when the water finally arrives in Silfra, it is so clear that you can see all the way along the fissure. This is the clearest freshwater in the world with a mind-blowing length of underwater visibility that exceeds 100 meters (328 feet). As the water from the glacier never stops flowing, the natural spring creates a gentle current that keeps the 2-4°C (35-39°F) water moving constantly, ensuring it never becomes dirty and that bacteria cannot thrive.

Þingvellir National Park is popular with tourists and is one of the three key attractions within the Golden Circle. There is a visitor center, where visitors can obtain an interpretation of the history and nature of Þingvellir. There is an information center near the camping grounds. There are hiking trails, such as the Execution Trail and the nearby Leggjabrjótur. Scuba diving has also become popular at Silfra Lake as the continental drift between the tectonic plates made it wide enough for divers to enjoy unparalleled visibility.

Information Sources: