The Punic War: The Punic Wars were a series of three wars fought between Rome and Carthage from 264 BC to 146 BC. At the time, they were probably the largest wars that had ever taken place.

First Punic War

The Battle of Messina in Sicily in 264 BCE precipitated full-scale war between Rome and Carthage. This battle began after an attack by the Syracusans, under Hieron II (d. 216 BCE), and the Carthaginians on the Mamertimes, the Campanian mercenaries hired by Syracuse to hold the seaport of Messina. The Mamertimes called on Rome for help, and the Carthaginians took control of the city. The Roman army then repelled the Carthaginians, and the Syracusans allied themselves with Rome. The Romans invaded western Sicily and besieged Agrigentum, a Carthaginian stronghold.

- PRINCIPAL THEATER(S): Sicily and the Mediterranean Sea

- MAJOR ISSUES AND OBJECTIVES: Rome and Carthage fought for control of the island of Sicily.

- OUTCOME: Rome won control of western Sicily and forced Carthage to pay a large indemnity.

Carthage sent Hanno (fl. third century BCE) with an army to relieve Agrigentum in 262, but he was defeated. At that point, Rome controlled most of the island of Sicily.

At Mylae in 260, the Roman fleet won a battle against the Carthaginians by using new methods of naval warfare—the corvus, a narrow plank employed to form a bridge to the enemy ship, and fore and aft turrets from which missiles were hurled. After invading the islands of Corsica and Sardinia, Rome turned her attention to northern Africa. Setting sail with about 150,000 soldiers and sailors, a Roman fleet of 330 ships clashed with the Carthaginians at Cape Ecnomus off the coast of Sicily. After a decisive victory, the Romans continued toward Carthage and landed 20,000 troops under M. Atilius Regulus (fl. third century BCE), who won a victory at the Battle of Adys in 256 and offered terms to the Carthaginians. These terms, however, were so severe that the Carthaginians rejected them and continued fighting. To bolster their strength, the Carthaginians engaged the aid of Xanthippus and a band of Greek mercenaries.

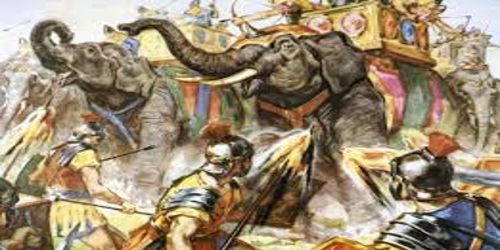

The hiring of Xanthippus proved to be beneficial to the Carthaginians. At the Battle of Tunis in 255, he defeated Regulus by using his cavalry, elephants, and phalanx of Greek mercenaries to good advantage. Approximately 2,500 Romans managed to escape back to their ships.

The following year, Carthage reinforced her strongholds on Sicily and recaptured Agrigentum. Suffering from the loss of nearly 100,000 soldiers when the Roman fleet went down in a storm, Rome nevertheless mounted an amphibious assault at Panormus in northwestern Sicily. In 251, at the Battle of Panormus, the Roman consul L. Caecilius Metellus (d. 221 BCE) defeated the Carthaginian general Hasdrubal (d. 221 BCE), who lost his entire force of elephants in Sicily. The Carthaginians sued for peace and sent the Roman general Regulus, who had been held hostage since the Battle of Tunis, to Rome to negotiate terms. Legend holds that Regulus advised his fellow Romans to reject Carthage’s proposals and then returned voluntarily to Carthage to honor his parole. He was then tortured to death.

The next major engagement took place at Drepanum. The Roman and Carthaginian fleets, each of about 100 warships, fought a battle that resulted in the loss of 93 Roman ships and 8,000 men, and a victory for Carthage. The Carthaginian commander Hamilcar Barcas (ca. 270–228 BCE) then repulsed the Romans at Eryx. Barcas fought off Roman assaults in western Sicily for the next five years, between 247 and 242. Rome continued to rebuild her military force and in 242 captured the Carthaginian strongholds of Lilybaeum and Drepanum.

The final battle of the First Punic War occurred on the Aegates Islands in 241. The Roman commander, L. Lutatius Catulus (fl. third century BCE), won a decisive victory, sinking 50 Carthaginian ships and capturing 70 others. The Carthaginians sued for peace, evacuated Sicily, and agreed to pay an indemnity of 3,200 talents over the next 10 years. Rome continued to hold western Sicily as her first overseas province, whereas Syracuse remained in control of the eastern portion of the island.

Second Punic War

Date: 218–202 BCE

- PRINCIPAL COMBATANTS: Rome vs. Carthage

- PRINCIPAL THEATER(S): Spain, Africa, and Italy

- MAJOR ISSUES AND OBJECTIVES: Carthage, under the leadership of Hannibal, sought revenge for her loss in the First Punic War with Rome.

- OUTCOME: Rome defeated Carthage and extracted from her a large indemnity and a promise to keep the peace.

- APPROXIMATE MAXIMUM NUMBER OF MEN UNDER ARMS: Carthaginians, forces, 59,000; Romans, 87,000

After being defeated in the First Punic War, Carthage relinquished her claims to Sicily and established a colony in eastern Spain. Known as New Carthage, the colony was ruled first by the Carthaginian general Hamilcar Barca (ca. 270–228 BCE), who had been victorious in the first war at Eryx and in western Sicily. When the general’s son, Hannibal (247–183 BCE), became ruler of the colony in 221, he set out to punish Italy for the crippling defeat Carthage suffered at her hands in the earlier conflict. In 221, he besieged Saguntum, the only city in Spain south of the Ebro River not under Carthage’s control. Saguntum, a Greek stronghold, was an ally of Rome, and when Hannibal refused to call off the siege, Rome declared war on Carthage. After an eight-month siege, Hannibal stormed Saguntum, thereby capturing the city from which he would launch his invasion of Rome.

Realizing that Rome controlled the sea, Hannibal decided to carry out his invasion by land. Setting out in March 218, Hannibal crossed the Ebro River with 90,000 men. After gaining control of the region between the Ebro and the Pyrenees, he left a garrison there to maintain his line of communication back to Spain and entered Gaul with about 50,000 infantry, 9,000 cavalry, and 80 elephants.

From July to October 218, Hannibal marched through Gaul. Having heard of Hannibal’s approach, Rome sent Publius Cornelius Scipio (237–183 BCE) to Massilia (Marseilles) to cut off the Carthaginians’ route. Hannibal evaded this block by turning north up the Rhone Valley. Scipio sent the bulk of his force to Spain and returned with a small army to the coast of northern Italy.

Hannibal then faced a formidable challenge: the snow-covered Alps. He managed to cross the mountains in 15 days but sustained heavy losses due to the climate and attacks by mountain tribes. Twenty thousand infantry, 6,000 cavalry, and a few surviving elephants reached the Po Valley.

Hannibal first engaged his enemy at the Battle of the Ticinus River, where he defeated the Roman army under Scipio in November 218. The following month, at the Battle of the Trebia River, Hannibal’s army, reinforced by recruits from Gaul, enticed the Romans to attack across the river while Mago (d. 203 BCE), Hannibal’s brother, struck the Roman flank and rear. Roman losses totaled about 30,000; Hannibal lost about 5,000. The Cisalpine Gauls were pleased with Hannibal’s victory over Rome, their longtime enemy, and about 10,000 Gallic soldiers attached themselves to the Carthaginian military.

Hannibal then took up winter quarters in the Po Valley near modern-day Bologna. In March, he was ready to press on. His army of 40,000 crossed the Apennine passes north of Genoa, marched along the seacoast, and pushed through the Arnus marshes to the Rome-Arretium road. The Roman commander, Gaius Flaminius (d. 217 BCE), rushed to meet Hannibal in battle, but the Carthaginian strategist had set an ambush for his enemy at Lake Trasimene. When the entire Roman force had marched into a narrow defile, Hannibal ordered his cavalry to close the northern end and his infantry to attack the Romans’ east flank. In the ensuing battle, one of the bloodiest ambushes in history, 30,000 Romans were killed or captured.

Over the next several months, from May to October 217, the Romans engaged in delaying tactics and sought only to harass Hannibal’s approaching army. At Geronium, the Roman commander, M. Minucius Rufus (fl. early 200s BCE), engaged Hannibal and was nearly defeated but was saved by the arrival of Quintus Fabius (d. 203 BCE), dictator of Rome. Hannibal quickly withdrew.

While Hannibal continued his push for Rome, his armies in Spain were forced to withdraw from the Ebro line. In Africa, the Romans persuaded the king of Numidia to rebel against Carthage in 213, but this outbreak was put down by Hasdrubal (d. 221 BCE) and a Numidian prince named Masinissa (ca. 240–148 BCE). Hasdrubal returned to Spain, but there the Romans had regained control of Saguntum.

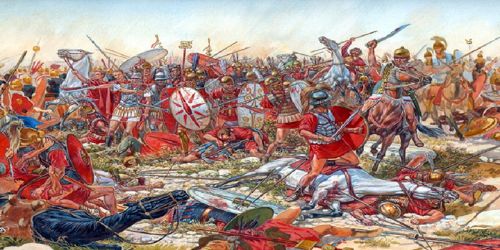

Meanwhile, the Romans organized 16 legions (80,000 infantry and 7,000 cavalry) to battle Hannibal’s army of 40,000 infantry and 10,000 cavalry. On August 2, 216, at the Battle of Cannae, Roman consul Terentius Varro (fl. early 200s BCE) sent 11,000 men to attack Hannibal’s camp. As the rest of the Roman army—72,000 infantry and cavalry—pushed Hannibal’s central line back toward the Aufidus River, the Carthaginian infantry wings wheeled inward and the cavalry struck from the rear. The Romans were surrounded, and a slaughter ensued. Compared to Hannibal’s losses of 6,000, the Romans suffered staggering casualties: 50,000 killed and 4,500 captured.

Despite three crippling defeats—at Trebia, Lake Tresimene, and Cannae—Rome persevered. The new commander, Marcus Claudius Marcellus (ca. 268–208 BCE), raised an army by pressing all able-bodied men into service. His two legions marched south from Rome to shore up the support from Rome’s allies. At the First and Second Battles of Nola, Marcellus gained a victory against Hannibal, further encouraging Rome’s allies to remain loyal. After the indecisive Third Battle of Nola, Hannibal marched toward the seaport of Tarentum, while his brother Hanno was defeated at Beneventum.

Beginning in 213 BCE, Marcellus besieged Syracuse, and in 211 he overwhelmed the garrison. Hannibal was successful at Tarentum in 212, but the Romans then besieged Capua, and Hannibal was forced to send Hanno (fl. third century BCE) to the city’s aid. The Romans foiled Hanno’s attempts and resumed their siege. Hannibal attacked the Romans at the First Battle of Capua, brought supplies to Capua, and moved on to the south coast.

Over the next winter, the Romans increased their efforts to capture Capua, keeping the city cut off from any aid from the Carthaginians. Hannibal’s army of 30,000 men made another attempt to relieve the city but was repelled. Instead of withdrawing in defeat, Hannibal pushed on toward Rome to try to draw the enemy force at Capua back to the capital city. The ploy failed, however, and Capua surrendered to the Romans in 211.

At the Second Battle of Herdonia, Hannibal defeated Roman proconsul Fulvius Centumalus (fl. early 200s BCE) and went on to Numistro, where he defeated Marcellus. Suffering a crisis of leadership, the Roman Senate called on 25-year-old Publius Cornelius Scipio (also known as Scipio Africanus) to take charge of the Roman army in Spain. This new commander soon gained control of territory north of the Ebro and then marched to New Carthage, while his fleet blockaded the city. The town fell in 209.

Battles followed at Tarentum, Asculum, Baecula, and Grumentum. The next major engagement, the Battle of the Metarus in 207 BCE, began when Hasdrubal withdrew his Carthaginian army, as reinforcements for M. Livius Salinator’s (fl. early 200s BCE) Roman army arrived on the scene. Hasdrubal’s forces got lost during the withdrawal and were forced to prepare for battle quickly at dawn. During the battle, Gaius Claudius Nero (fl. early 200s BCE) attacked Hasdrubal from the rear. This surprise attack demoralized the Carthaginians, who lost more than 10,000 men, including Hasdrubal, in the battle. Hannibal learned of his brother’s death when the Roman army catapulted the severed head of Hasdrubal into Hannibal’s camp.

The Roman army continued to press the advantage, and at the Battle of Ilipa in 206, Scipio’s army of 48,000 defeated 70,000 Carthaginians, thereby ending Carthaginian rule in Spain. In 204, Scipio invaded North Africa with an army of 30,000. During the winter of 203, Scipio attacked the Carthaginian and Numidian camps at night, wiping out the entire army, and then renewed his siege of Utica. The Carthaginian Senate soon sent for Hannibal, and the general set sail from Italy. Upon his arrival, the Senate helped him raise a new army. He then marched to Zama with 45,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry in an attempt to draw Scipio’s army away from Carthage. The ploy worked, and Scipio soon followed Hannibal toward Zama with 34,000 infantry and 9,000 cavalry. At the Battle of Zama in 202, the Romans quickly smashed the first two lines of Carthaginian infantry as the Roman and Numidian cavalry drove Hannibal’s cavalry off the field. At first, the third line of Carthaginians, the hardened veterans of many battles, held their own, but when the Roman and Numidian cavalry attacked the line from the rear, the battle was over. More than 20,000 Carthaginians were killed in the battle, and 15,000 were taken prisoner. Carthage sued for peace, surrendered all warships and elephants, and gave up control of Spain and her Mediterranean islands. Carthage also agreed to seek the permission of Rome before engaging in war and to pay Rome 10,000 talents over the next 50 years.

Third Punic War

Date: 149–146 BCE

- PRINCIPAL COMBATANTS: Rome and Carthage

- PRINCIPAL THEATER(S): Northern Africa

- DECLARATION: 149 BCE.

- MAJOR ISSUES AND OBJECTIVES: Rome wanted to keep Carthage under its control and prevent her from waging war on Numidia.

- OUTCOME: Rome utterly destroyed Carthage, sold the surviving Carthaginians into slavery, and took control of North Africa.

CASUALTIES: Only 50,000 of 225,000 Carthaginians survived the destruction of their city.

Fifty years after the end of the Second Punic War, hostilities broke out between Carthage and Rome’s ally Numidia, despite promises made at the close of the Second Punic War by Carthage to gain permission from Rome before waging war. The Roman Senate demanded that Carthage cease operations against Numidia, send 300 hostages to Rome, surrender her weapons, and dismantle her battlements. Carthage complied with these demands but refused to accede to Rome’s final demand: to abandon the city of Carthage and move the population inland. In 149, Rome sent a large force to Carthage, but the Carthaginians mounted a strong defense and managed to thwart Roman’s attack. In 147, Scipio Aemilianus (ca. 185–129 BCE) arrived in Africa with the Roman army and blockaded the city of Carthage by land and sea. After holding out for three years, the city fell in 146 BCE, following a house-to-house conflict. At the end of the battle, 78 percent of the Carthaginian population had perished from starvation, disease, or in battle. The Roman Senate ordered the city completely destroyed and sold all survivors into slavery.

Information Source: