Different people have different opinions and perceptions of what is considered social, and what is considered socially acceptable may change over time and between cultures. So, socialness is a subjective concept and it is shaped by individual experiences, cultural norms, and personal beliefs.

The perception of socialness can vary greatly among individuals and can be influenced by a number of factors such as personal experiences, cultural norms, and individual biases. What one person may view as sociable, another person may not, and vice versa. Ultimately, the interpretation of socialness is subjective and dependent on the individual perceiving it.

According to a new Dartmouth study, while people are generally predisposed to perceive interactions as social even in unlikely contexts, they don’t always agree on which information is social. According to the findings, much of the brain responds more strongly to information that is interpreted as social rather than random.

The findings, which were published in the Journal of Neuroscience, contribute to research on how humans are drawn to social connections. Humans have long been known to perceive social information in inanimate stimuli, such as seeing a face in a rocky outcropping or interpreting the motion of two shapes, as a social interaction.

Humans depend on social structures to survive. Our brains and minds may be programmed to perceive things as social in order to gain an evolutionary advantage.

Emily Finn

Previous studies on social perception that used such geometric-shaped animations frequently relied on labels assigned by researchers more than 20 years ago that specified which animations should be classified as social versus random, or nonsocial, motion. Dartmouth’s study, on the other hand, takes a more subjective approach and is based on participants’ own reports of whether they perceive a given animation to be social or not.

“We wanted to know how and why people perceive the same dynamic social information differently,” says lead author Rekha Varrier, a postdoctoral fellow in the Functional Imaging and Naturalistic Neuroscience (FINN) Lab at the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences. “By considering people’s perceptions, we can better understand the underlying neural processes.”

The Dartmouth team used data from the Human Connectome Project’s social cognition task to investigate the behavioral and neural correlates of “conscious” social perception. With over 1,000 healthy adult participants, the project provides researchers with a large, public dataset to work with.

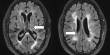

Participants were asked to watch 10 animations of two or more shapes in motion for 20 seconds while their brain activity was recorded in an fMRI, or functional magnetic resonance imaging, scanner. The task was designed to be balanced, with five of the animations intended to be social and the other five not. After watching each animation, participants were asked to indicate how they perceived the content by selecting one of the following labels: social, nonsocial, or unsure.

The findings revealed that participants were biased toward perceiving information as social, as they were more likely to label an animation intended to be random as “social” than one intended to be social as “random.” Furthermore, when the stimuli were intended to be perceived as nonsocial, participants expressed greater uncertainty about how to categorize animations, possibly indicating a reluctance to label content as nonsocial entirely.

“Humans depend on social structures to survive,” says senior author Emily Finn, an assistant professor of psychological and brain sciences, and principal investigator of the FINN Lab. “Our brains and minds may be programmed to perceive things as social in order to gain an evolutionary advantage.”

Finn also notes, “We’re likely tuned to see social information in our surroundings because the cost of missing a social interaction would likely be higher than that of falsely perceiving something as social.”

“Our fMRI results indicate that much of the brain cares about social information,” says Varrier. “We found that the neural response to social content occurs early both in time and in the cortical hierarchy.”

The findings show that social information is processed in early brain regions that are typically involved in visual information processing, such as the lateral occipital and temporal regions. The researchers hope to develop their own set of deliberately ambiguous animations in the future, allowing them to ask more specific questions about why people perceive social interactions differently. The findings could be used to gain a better understanding of autism spectrum disorder and a more nuanced understanding of social perception.