According to a recent study, just one species of the more than 7,000 remaining frogs has real teeth on its lower jaw, ending a long-standing debate.

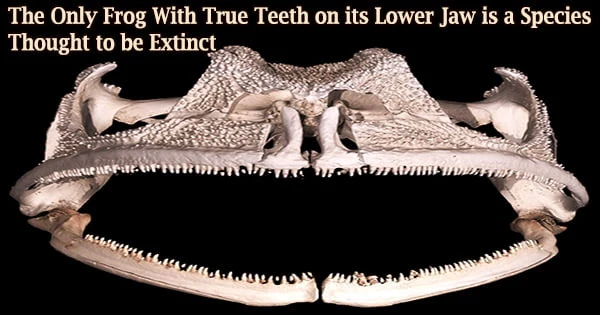

The offender, a large marsupial frog known as Gastrotheca guentheri, has puzzled researchers ever since it was discovered in 1882 because it appeared to have a full set of jagged, dagger-like fangs on the top and bottom of its mouth.

On the specific composition of these structures, scientists have argued since that time. Because frog teeth are so little, it is renownedly difficult to discern the specific tissues that constitute real teeth, such as dentin and enamel.

“They’re incredibly small, each about the size of a grain of sand,” said lead author Daniel Paluh, a doctoral candidate in the University of Florida’s department of biology. “There’s no way to confirm the presence of dentin and enamel in frog teeth without using high-resolution techniques.”

Frogs have been without teeth on their lower jaw since they first appeared in the fossil record more than 200 million years ago. A well-known biological concept known as Dollo’s Law, which states that once a complex trait is lost in an organism, it never recovers, made the presence of a single living species with a complete dentition seem at best implausible.

Frogs, however, have a reputation for breaking the rules when it comes to their teeth. Despite the fact that their basic body shape and anatomy have largely remained unchanged since the Jurassic period, Paluh and his colleagues recently discovered that frogs have lost their teeth on more than 20 different occasions and may have regained them an additional six times throughout their evolutionary history.

Some species, such as those that feed on termites and ants, are toothless, and they must instead catch prey with their sticky, projectile tongues. For stopping wiggling prey, larger prey-hunting frogs usually have a row of teeth on their upper jaw and a toothy, serrated palate on the roof of their mouths.

We’ve seen many species in this group become endangered due to climate change, habitat degradation and chytrid fungus disease. We won’t be able to answer these questions in any other group because these traits don’t exist anywhere else in the frog tree of life.

Daniel Paluh

On rare occasions, some animals have grown enormous bony fangs that project from their lower jaw and resemble teeth on the outside, but lack the normal dentin and enamel layers. In addition, unlike other frog species whose teeth are replaced via a conveyor belt, fangs only grow once and cannot be replaced.

It was debated for many years as to whether the characteristics on G. guentheri’s lower jaw were actual teeth or merely fake bones. Finding a specimen to respond to the question wasn’t easy, though.

G. guentheri, which is indigenous to the cloud forests of Colombia and Ecuador, was last observed in 1996, prompting worries that the species may have since gone extinct.

Although there are a few G. guentheri specimens conserved in museums, biologists are hesitant to subject them to the kinds of harmful tests required to study their teeth due to how uncommon these specimens are.

However, due to a unique feature of Gastrotheca’s biology, Paluh was able to use a preserved embryo rather than an adult as a sample. Instead of laying their eggs in ponds or streams, female marsupial frogs carry them in a pouch on their back.

“In the case of G. guentheri, these eggs will skip the tadpole stage and hatch directly into miniature versions of the adult called froglets,” Paluh said.

The researchers used CT scans of the embryo’s jaws to painstakingly stain very small fragments of individual teeth with dyes that bond to dentin and enamel. The teeth of G. guentheri were similar to those of other frog species in terms of overall structure, development, and the tissues they were composed of.

“This was surprising given the extreme length of time since they were lost and regained,” Paluh said. “Our expectation was that if they did regain teeth, they would somehow be different, but that’s not what we saw at all.”

Paluh hypothesizes that the intricate developmental pathway for the teeth, which is still present in the majority of living frogs, may hold the key to explaining how features that had been lost for millions of years unexpectedly reappeared in a seemingly unremarkable frog.

Despite the fact that teeth vary in location depending on the species, the same basic genetics probably controls their development, and producing teeth in the lower jaw may be as simple as flipping a switch.

In the near future, Paluh plans to utilize a range of genetic techniques to map the contours of tooth development and evolution in frogs, but for G. guentheri and a number of other imperiled species in the American tropics, it may no longer be able to ascertain the precise answer.

Due to DNA degradation over time in plants and animals housed in museum collections, the few old G. guentheri specimens are unlikely to be valuable sources for genetic research.

“We’ve seen many species in this group become endangered due to climate change, habitat degradation and chytrid fungus disease,” Paluh said. “We won’t be able to answer these questions in any other group because these traits don’t exist anywhere else in the frog tree of life.”